For Sasha Joseph Neulinger, filmmaking has always been the family currency. His father Henry Nevison was so movie mad that in high school he created a club so he could borrow prints from the Philadelphia Library’s reserves when they wouldn’t rent out films to individuals and began making them himself soon after, eventually starting a business with Sasha’s mother Jacqui Neulinger to produce films and commercials for local businesses in Philadelphia. As Henry can be heard saying, “Movies are there to capture the good times,” which is what led Henry to accumulate over 200 hours of footage of Sasha and his younger sister Bekah growing up.

In retrospect, however, these home movies could only be looked back upon in horror, serving as evidence of sexual abuse that occurred within the extended family when Henry unwittingly captured footage of kids’ abject disgust, unable to articulate themselves verbally, but showing a disillusionment with the world that’s well beyond their years. Yet if film could freeze this traumatizing moment in time as vividly as it would continue to live in the minds of those who endured it, Neulinger would find that it could also help his immediate family move forward after leaving Philadelphia for Montana State University where he graduated with a degree in film and an ability to put the past into a proper context.

The powerful result is “Rewind,” which may unfold as an unthinkable tragedy, but is illuminated with the knowledge that Neulinger, once completely incapable of expressing his experience, gets to tell his story with great confidence, describing how patterns of abuse that began generations before his made their way down the family tree on his father’s side and how fallible the system that’s set up to pursue such crimes is, requiring survivors of abuse to relive their experience time and again as they provide testimony to satisfy lawyers and law enforcement over the course of countless years. The remarkable composure and empathy that Neulinger can be seen showing from his earliest years extend into his filmmaking, offering his immediate family the chance to share their experiences and reconcile how they handled things based on what they knew and, in some cases, felt they could not share with one another at the time.

A year after “Rewind” premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival where it received a special jury prize, the film will be available on VOD starting today and air on May 11th on PBS Independent Lens and Neulinger spoke about having the perspective as an adult to reflect on such a painful part of his childhood with clarity, having a crew he could trust to collaborate with and how the movie has already changed his life and his hopes for how it could change others’.

Yeah, right before I started this project, I was 23 years old, just finishing up film school at Montana State University, and in many ways, I was working hard to move forward into the next chapter of my life. My last day in court was the day before my 17th birthday and a year later, I moved to Montana, so really [it was] the first four or five consecutive years of my life where abuse wasn’t the primary focus of my existence. I was working for Grizzly Creek Films on a National Geographic show and things were good, but there was still this voice in the back of my mind that said, “Sasha, you’re dirty, you’re disgusting, you’re unlovable.” And I understood that that voice was from unresolved issues in my childhood and I wanted to confront those issues so it wouldn’t continue to plague me into my adult life.

I figured that I might be able to find some answers in some home video. so I called my dad and asked him, “Dad, do you have some of those home videos from when I was a kid?” and to my surprise, he said, “I’ve got three huge boxes. I’ve got over 200 hours of home video, I’ll send them to you.” So I watched the first six tapes, and in those first six tapes, for every question that I was able to answer, I had ten new questions. So I recognized that this was going to be quite a huge endeavor and I realized that if this process turned out to be positive and cathartic, it’s a process that deserves to be shared with the world.

It was there that I decided to make this film and my dad and my mom were instantly supportive. My sister [Bekah], at first, was kind of angry with me. She said, “We just got through this. Why do you want to dig this back up?” And I said, “Bekah, we survived this, but survival isn’t enough for me and I don’t think it’s enough for our family. I don’t want it to be enough for our family. I want us to be able to truly understand and unpack and heal the wounds from what happened to us so we can truly move forward with our lives.” She was skeptical at first, but when we had success with our Kickstarter campaign and she saw thousands of messages from survivors around the globe, responding positively, she came onboard. From there, the rest is history. My family followed my lead in this journey to unpack and hopefully heal from what happened.

You’re seen asking questions throughout the film, which is certainly understandable, but when you’ve lived through both the experience and the trial, did you have a fairly complete version of the story in your head before filming?

Before we started production, I sat down with the whole team and we must’ve talked for four hours [where] I chronologically laid out the whole story from my subjective experience – everything that I experienced and I had a vision for how this story would come together, but it was really important to also recognize that the point of this film isn’t just to tell my story, but to learn fresh perspectives. What was so important about the process of making this film for me was staying consistently aware of and practicing the idea of juxtaposing and reconciling my subjective childhood experience with my newfound objective adult lens. Part of that is holding space for others to add bits from their experience because that’s where the true growth and healing can happen.

There was a lot that I knew in my mind from my experience, but I learned so much about what happened through talking with my mom, my dad, my sister, my psychiatrist, the detective and the prosecutor because ultimately, I was a kid when all of this happened, so there’s only so much a traumatized child can understand as they’re going through the process. Being able to go back years later and discuss it with a fresh lens helped me recontextualize why it took nearly nine years for prosecution to run its course, why my abusers were allowed in the home, why my mom couldn’t help me sooner. So there were huge discoveries that I made as a result of embarking on this journey that added to what I had already known and in some ways shifted preconceived notions about how things went down.

I really felt that as much as we could when we’re talking about important moments from the past, if we could go to those places, it might inspire a vulnerability and emotional openness. I also just felt that visually, if we’re talking about it, let’s be there. The film utilizes the time machine that is home video, so we can go to the past and confront it through the home video, but we can also go there by choice versus in the present moment as adults. In the same way that it’s helpful to look at a drawing or a photo or a clip of home video, I think it’s also helpful to revisit these places that hold significance.

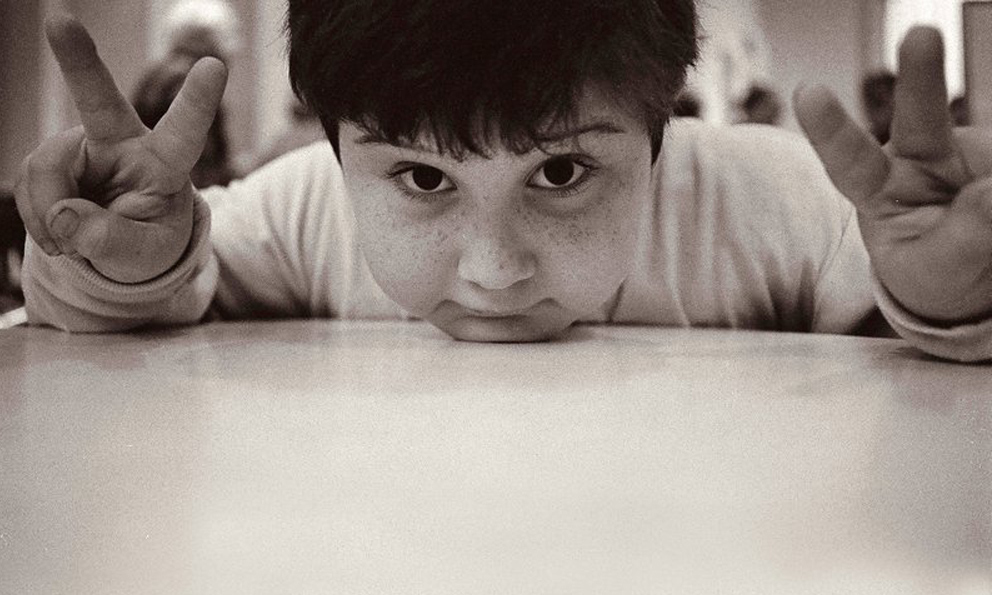

There are also these really striking black-and-white photographs throughout from when you were a child. Were those part of your father’s archive as well?

All the black and white photos in our film were from my uncle John Solem, who I love to call my one and only great Uncle John. He started dating my mom’s sister Barbara before I started disclosing what happened – he married into the family, and he’s not an abuser. He’s completely separate from it all, but he’s an incredible professional photographer — he’s legally deaf, so he can technically hear a little bit, but he’s very hard of hearing, and he really experiences the world through his eyes. That comes through in his photos and that archive was to me almost just as important as the home videos. It was an embarrassment of riches when it comes to visual assets to tell a story that takes place decades ago.

Was it a challenge to crack the structure of this as far as when to introduce people?

Very early on, my team and I realized we don’t want to make a four-hour film about child abuse. We want to get in, say what we want to say, not beat around the bush and then we need to get out. We have to honor our audience. [The film] should be hard, but it should also be watchable and hopefully rewarding at the end, so the hardest part was being able to step back and objectively recognize that there were incredibly emotional, beautiful scenes that I wanted in the film, we had to cut things in order to honor our audience and the structure. Every scene ought to answer a question and ask two more.

I’ve got to give so much credit to our editor Avela Grenier. She had a 12-foot cork board where it looked like she was a detective trying to find a serial killer. [laughs] We had color-coded characters, years, places, cycles of abuse – we color-coded and organized them and she did so much legwork on because I obviously understood every single moment of footage because it was my life, but Avela put so much energy and time into watching and rewatching every clip, making sure that she understood it just as deeply as I did subjectively. Having that relationship and being able to have really hard conversations about the narrative and how it would flow was possible because of that work she put in.

Yeah, right off the bat, if an editor shows a director a cut of a scene, usually a director can look at it objectively, make notes and then we’re done. My first watch on anything [for this film], whether it was raw footage or a scene, the first time I would watch it, it was just for me. I didn’t want to rob myself of the emotional cathartic experience of just seeing what was in front of me. But then after that, I would watch it a second time or sometimes even a third time and come back with objectivity and have a creative conversation. But I couldn’t have made this film in a vacuum. It’s so important because of how personal and emotional this story is, I knew I needed to have a team of objective, talented filmmakers I could trust to bring a different and fresh perspective into this because I wanted to share my story authentically from my own heart, but also make sure that I wasn’t making assumptions about what the audience could comprehend. Having an objective team that I trusted really helped balance that.

What’s the last year been like, taking the film on the road?

2019 was the biggest year of my life. It was so incredible to premiere at Tribeca in New York where the man who said, “If you tell anyone, I’ll kill you,” lives, and to be able to premiere in his hometown, owning my voice and owning my power. That felt incredible and from there, we were in Rome, Paris, London, Toronto and now with the film being accessible with digital on demand and accessible to 280 million households nationwide through Independent Lens and PBS, it’s incredible. But on a personal note, the catharsis for me came full circle. We premiered at Tribeca, and I got married a few months later and my wife and I closed on a property and built a house and we adopted a puppy. I can honestly say I’m living my best life today and it is because of the decision I made seven years ago to confront my trauma head on, and with the work I get to do sharing my knowledge with law enforcement, child protective services, mental health professionals – I’m doing everything I can to make the world a better place for future generations of children while also doing everything I can to honor four-year-old Sasha by living the best life I can possibly live.

“Rewind” will be available on demand here on May 8th. It will air on PBS’ Independent Lens on May 11th at 10 pm.