When Scott Cummings approached Peter Gilmore, the High Priest of the Church of Satan, about making the film that would become “Realm of Satan,” they found themselves speaking the same language fairly quickly, trading movie suggestions for each other to watch to get an idea of what they might be able to expect from one another if there was a partnership. There is no arguing that the members of the church are naturally cinematic, dressing in black, performing magic and conducting tarot readings, but Cummings, a gifted editor on such films as “Menashe” and “Never Rarely Sometimes Always,” recognized what would make a movie is what he came to realize himself as he was invited into homes around the world and walked down to basements and backrooms where members would often live uninhibited by public view, expressing how much they are a part of the culture already.

Noting in its introductory title cards that it was made “in collaboration with the Church of Satan,” “Realm of Satan” unlocks doors in the mind as it does in the world as Cummings takes in one surreal scene after another that through stationary framing can be made to look mundane, from a woman wearing a pair of antlers that are set on fire to commanding “forces of darkness to bestow their power upon you.” The director doesn’t hide identities of the people he meets or their geographical locations, but doesn’t announce them either, making it possible to think that you’re peering in on a next door neighbor, though with their beliefs they’ve had to forge their own communities. While movie magic can help illustrate ideas that have surely only lived in the imaginations of its members, the nature of the collaboration allows the members to express their lifestyle and beliefs as they see fit, full of mystery and wonder that can be intoxicating, but disturbing and distancing without context, which Cummings finds more at odds with reality than what they practice.

Gradually tightening its grip on an audience as portrait-like scenes of members start to reveal a larger canvas, the film starts to take shape around the death of Joe Netherworld and the subsequent arson that destroyed his famed Halloween House in Poughkeepsie in 2021, and when the landmark that once brought together people of all beliefs as a fascinating attraction was destroyed, it can be argued that Cummings has built another in its place, rewarding curiosity and open to any number of interpretations. With the film making its premiere this week at Sundance, the director spoke about what it meant to forge a creative partnership with the subjects of the film, how he created a sense of adventure for himself that now spills out onto the screen and why everyone should be concerned with protecting subcultures at all costs.

I had made a previous 30-minute film [“Buffalo Juggalos”] that was similar in non-fiction space, but participatory [where] I worked with a community essentially of crazy maniacs and made a crazy film with them. The film was pretty well-regarded and I was looking for a new subject to work with and Satanism and its mythology had been something that swum around my life and my head for many years, even though I didn’t know that much about it. It’s just informed so many things I love – it influences all of our horror movies, and when I was younger, I was into metal, so I decided maybe these are interesting people who would make a crazy film. I just reached out to them cold, not expecting much. We started talking and there was a long time where it wasn’t clear that anything was really going to happen, but then all of a sudden we were shooting a movie together.

What was it that clicked for you on “Buffalo Juggalos” in terms of thinking how to approach a subject like this?

When I started that film, as an editor, I had this horrible lifestyle where I just sit in these terrible office rooms and never get to go anywhere cool. I traveled a ton in my youth and I’m so jealous of cinematographers because they get to go to Peru or something and I’m just sitting in some dumpy office in New York. I also come from a fiction background, but the idea of sitting down and writing a script isn’t so much what I was into, so I [thought] I like going weird places and I’ll meet some weirder people and have a weird experience and make this thing. That’s how “Buffalo Juggalos” came about, like “Hey, I want to have an experience myself. I’m going to go live with these people and essentially see what they’re about and lose myself in it.” I just loved that process and I liked the idea of collaborating, so with the Satanists, it was very similar where I wasn’t able to live with them, but I was able to go into their world and become a part of it. And that was all I wanted in life – to be able to like go interesting places and meet interesting people.

Which you give the sense of in how this is structured where it feels like you’re opening doors in the world around us to discover these can be your next door neighbors. I wondered if filming actually mirrored your own experience to some degree when you really find a way to show your subjects and their surroundings so vividly?

Yeah, it’s interesting because some of the people I knew very well by the time we started shooting, but I had very distinct ideas about what we wanted to do. I didn’t meet them all [beforehand] and sometimes I’d just show up at their house and be like, “Okay, what the heck are we gonna do here?” And then we’d spend time together and talk and get to know each other and I was pretty open about my intentions and where I’m coming from. The high priest of the Church of St. Peter was vouching for me too, and others who worked with me, so it made the relationships a little easier. It wasn’t hard to find common ground with people because usually people are pretty upfront about what they’re interested in, so [you see] “This person is very into S & M” or “This person is into metal work,” and then you figure out ways to fold that into the film and obviously, we shot a lot more than we used, but it’s a bit like fishing where you’re collecting the pieces, and then you get the outline of a puzzle and then you figure out how to finish the puzzle. Of course, there was stuff that I was heartbroken to take out, but that’s that’s just the way it goes.

To extend the fishing metaphor, how big did you want to cast your net? It looks like it was an international production.

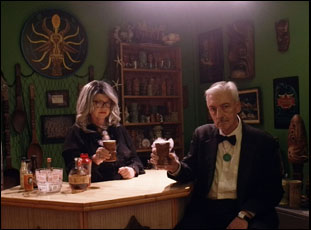

It was very important to me to make it clear that Satanism is is a worldwide religion, not just American. There is obviously a significant presence in the U.S., but there’s a lot of members actually in Central America — I didn’t really get on [that] because there were too many trips, but I wanted to make sure [you saw], “Hey, this isn’t just the gothy person in town. There’s also a normal-looking guy in Scandinavia,” who’s actually occult royalty, and it’s been around a long time and has a history. There are people everywhere that are curious about it, and “The Satanists Next Door” was a major touchstone for me because I met those people all the time. I would a suburban 70-years old married couple in Jersey, but then but they’re Satanists and it’s like “Oh okay,” but there was total secrecy [about] this. That’s something I always loved about Satanism is that they could be anybody. It could be your neighbors, It doesn’t have to be who you think it is. The Church of Satan has always been purposely mysterious about membership and who’s a member and that’s nice, actually. Everybody can be a member.

There are nods throughout to the Joe Netherworld house and how it was the site of an arson attack. Was that something you could look to as a skeleton when it doesn’t have any traditional narrative structure?

Intentionally, it was always intended to feel very random at first and then people would start coming back and then [the film] would coalesce into this ritual, but then I realized, there was always a documentary element [of] learning about things without maybe realizing it. Joe Netherworld was not [in the film in the way he is now] initially, because Joe was alive actually when I started the film, and the house was still there. There’s a documentary alone about Joe’s house being burned down, but I didn’t totally think that would be interesting to me [to make]. But I felt very connected to him. I’d been outside that house, and it was like a hole in the street. I could see the hole, and I’d just drive by it all the time, and it was just such a hole that had been left in their community [when he passed] that I realized it was so important and to ignore it would be a big mistake. [I thought] there’s just something here that needs to be in the movie. It’s communicating to me. I have to listen. There’s some magic going on here that I need to take note of.

But it said something too [about how] subcultures like theirs are always in danger. They’re very fragile things — independent film included. The world is actually quite hostile to them and will come and burn them in their house and they’re not the dangerous ones. “It’s the not Satanist that’s the one who’s the threat. It’s you.” That’s been borne out throughout history with witches and witch hunts for hundreds of years, so [I realized] this is really actually an important part of the history of Church of Satan that’s happening right now. [Joe Netherworld] was an iconic figure, and that house was iconic, and it was also so tied to one of the participants who was his best friend and you can’t spend half an hour with [them] before [they] start going into “Joe would have loved the film, and Joe should have been in the film…” So there was also a desire to bring it to the film in some way and that’s how we did it.

If this has been on your mind for the past seven years, what’s it like to get it out into the world?

It’s great. I’m still processing it, and it’s hard [also]. It feels like I was so deep in this kind of thought. All I’ve read for years is [Church of Satan] connected books and I’ve watched the COS film list, which is actually quite a good film list if you ever look at it, so that’s no problem. But I’ve just been so immersed in this environment, going back a little bit to normal life is a grief process for me, I do have to like think about, “Okay, is there is going to be something next I’m going to throw myself into as crazily [as this]?” But still I’m very friendly with a lot of the people in the film and it was just like such a wonderful ride for seven years.

“Realm of Satan” will screen at the Sundance Film Festival on January 22nd at 10 pm at the Redstone Cinemas 7 in Park City, January 25th at 7:45 pm at the Holiday Village Cinemas in Park City and January 26th at 9 pm at the Broadway Centre Cinemas in Salt Lake City. It will also be available to stream from January 25th through 28th.