If Maite Alberdi ever had to think about the importance of what she was doing in making “The Eternal Memory,” she only needed to refer back to archival footage of her subject Augusto Góngora when he was one of the few reporters to report without fear about the atrocities committed in his native Chile under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet during the 1970s and ‘80s. His book “The Forbidden Memory,” published in 1989, became one of the few ways that Chileans could find out what really happened in their own country when media was largely controlled by the military regime, and Góngora made it his mission to not let the torture and murder of thousands in Pinochet’s name to be swept under the rug, even as the general stopped at nothing to suppress the flow of information to the public. However, it was a torch that Góngora couldn’t possibly carry on forever, cut even shorter upon learning he has Alzheimer’s at 62, yet just as he once preserved a record of what he experienced in real time for future generations, Alberdi takes on the same responsibility as she captures Góngora’s twilight years in the care of his devoted partner Paulina Urrutia, an equally revered icon in Chile as an actress and a former minister of culture.

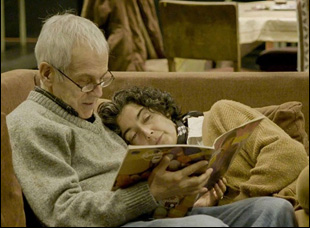

Alberdi, who previously offered a poignant peek inside a nursing home where residents remained active in her Oscar-nominated “The Mole Agent,” once again offers a tender portrait that could only be told in time, charting the 20-year courtship between Góngora and Urrutia that yields a love for the ages and only seems to grow stronger after Góngora’s diagnosis. The director tucks into Góngora and Urrutia’s life of routine where the latter keeps her partner engaged by taking him to her play rehearsals and teasing him with bits of their history that he may not immediately remember, excited when recalls something and trying to stay amused when he cannot and while there are inevitable frustrations with the memories that are gradually robbed from him, Alberdi is there to capture what cannot be taken as Urrutia remains steadfastly by his side and appearing in her eyes as formidable now as when the eyes of an entire country were on him and offer yet another reason for hope after a lifetime of being a beacon of light for so many.

After the film’s premiere at Sundance where it picked up the Grand Jury Prize for World Cinema Documentary, “The Eternal Memory” is now opening in theaters where it carries on the legacy of Góngora, who passed away peacefully in May, and Alberdi graciously spoke about her ongoing interest in shining a light on people at this age, her rare ability to tell deeply emotional stories without a heavy hand and constructing a savvy structure for the film that would honor Góngora’s condition but his ongoing thirst for life.

I think there is an important connection in the films that it’s related to fragility. You see in “The Mole Agent,” people depend on others and they are completely isolated from society and are isolated because they are fragile and dependent. And in “The Eternal Memory,” it’s the opposite. It’s a fragile man whose wife decides to not isolate him from society, it’s to integrate him.

How did you first connect with Augusto and Paulina?

I knew them for all my life because they are famous people, so I really knew who they were. And Augusto was very important in my life because I admire his [news] programs, but I read an interview when he openly said that he has Alzheimer’s and a couple of months later, I was hired in a university to [give] a lecture and Paulina worked there, and she was with him in the work, so when I saw that, and I saw that they were in love in the middle of the work, it was unbelievable.

Was it any different to make a film about such public figures, not just in the fact that they were well-known, but also well-documented?

When I started the film, I was not thinking about their careers or that they are famous people. I was completely focused on making a film about a couple that were in love. And for me it was a love story and I realized that I cannot construct a love story without see the background of this couple and it was impossible to make a love story without understanding the work because in the relationship, the work was not disconnected from the love. That’s when the archives and their careers start entering the film, and I feel that Augusto sent me signals of what I have to put [into the film] of his past. He’s the one that never forgets, like the loss of his friends during dictatorship, so it was like, “Okay, I have to speak about that loss. I have to speak about what did he do during dictatorship as a journalist” that he’s still remembering. So this love story started to get connected with the past because he was remembering something of that past. That’s why it’s an eternal memory for me because there are things that they’re always there, always in that body.

It was when I [read] the opening of Augusto’s book [“The Forbidden Memory”], at the very end, he said the only way to construct a historical memory, it’s to build our memories thinking about what the history provoke, like the feelings that we felt with history. That speech was 30 years ago, and [I thought] “Okay, this year is the 50th anniversary of when militaries took the country,” and in this moment, what he said is meaningful because he’s saying we don’t have to remember dates. We don’t have to remember numbers. We have to remember what did we feel. And that is the exercise of this film, because he doesn’t remember how many years he has been with Paulina, but he remember his love, he remember his pain, [the film becomes] a historical exercise too, of how we understand commemorations. Like do we need to say the number of dead or the number of years? What do we need to continue repeating to new generations?

Do you think about structure as you’re filming or does it only happen once you get to editing?

No, I completely did it in the editing because I understood that it can’t be linear, because if I did it completely chronological, [we know] the end of the people with Alzheimer’s. We realized that we need to construct not a narrative story, but construct an emotion and a memory and a way to construct that memory and that emotion is with associations that are not directly related. It’s like how we relate or associate scenes from the past to give meaning to the present.

When COVID hit, I understand Paulina had to film some of this and you also obtained this trove of home movies from 20 years ago. Was it interesting seeing what they actually filmed themselves?

Yeah, it was amazing because I think that the film is shot by the three of us. The [actual celluloid] film is shot by Augusto 30 years ago, then by me and [eventually] by Paulina taking the camera. When I started film, it was completely an emotional approach, and I didn’t expect to get that archive, or that footage of Paulina herself shooting the relationship. When I received that material, it was completely like, “What is this?”And Augusto’s archives allowed me to understand how [he and Paulina] have a relationship that never changed. They have exactly the same love the first day and the last day, and it was very lucky and heartbreaking in the editing when I put together that image and I see the same look [they gave] each other 30 years ago and now because I have never seen that in fiction films and I never seen that in life either, but I love that you really see that it’s exactly the same. It was unbelievable for me to put it together and when I saw the material alone, it was not the heartbreaking thing that I felt in the editing, but it’s what the audience feels when they see the film, and when we did it with the editor, it was completely difficult for us to live it.

Too much in an emotional way? Yeah, I think that in the editing process, we test a lot with other [people], because at some point you are so in that you lose [perspective], but I learned in both films that your feelings are the same as the audience at the end. And in “The Mole Agent” and “The Eternal Memory,” [documentaries are] not a genre like a drama or a comedy. You have all the genres inside you. You pass for light and then you go to darkness, so the equilibrium for the audience is to know that life is mixed. And in “The Eternal Memory,” you can see a bad night [that Augusto has] and then in the morning he’s dancing. That was exactly how it’s happened [in reality].

At the end, it’s more lightness than anything, even if the structure is a drama, because if you wrote [about these films] on paper, it’s people that are alone and isolated in a retirement home, but it has a lot of light, or a man that has Alzheimer’s and you can say, “Oh, it’s terrible,” but it’s not. [This couple is] living a very happy relationship at the end, so you have to celebrate love. So I never think that it’s too much for the audience. I try to balance the emotions and to have all the emotions there, because in life you live in mixed emotion. It’s not like you are depressed and you don’t feel anything else. Sometimes everything is more confused in a way.

What’s it been like to get this out into the world?

It has been a very grateful experience because as a documentary filmmaker, the experience that I show to the audience is the experience that I also live. It’s my life too [in] there, and it’s great because it’s a way to share an experience that I loved to have. You really want to tell everybody, you have to see it and I’m really happy that my experience is [now] going to be the experience of others too.

“The Eternal Memory” is now open in New York at the Angelika Film Center and the Jacob Burns Film Center and opens in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal and the Encino Town Center on August 18th.