The opening frames of “The All-Americans” (previously titled “The Classic” for its debut at the L.A. Film Fest in 2017) are as striking for what’s onscreen as much as for what they imply. With scenes from the streets of East Los Angeles where you’re more likely to hear Spanish spoken than English as people bustle around just to get by, the air is filled is filled with the contempt on talk radio where call-in hosts stoke fear with such proclamations “Los Angeles is turning into Mexico.” By simultaneously presenting the cacophony of the public debate in the U.S. around immigration with a clear-eyed, ground level view of the life that immigrants have built for themselves, director Billy McMillin gets at the dialogue that we should be having, stripped of political rancor and offering up in its place a compassionate look at Americans, both natural-born and recently arrived, that are finding a place in this new normal.

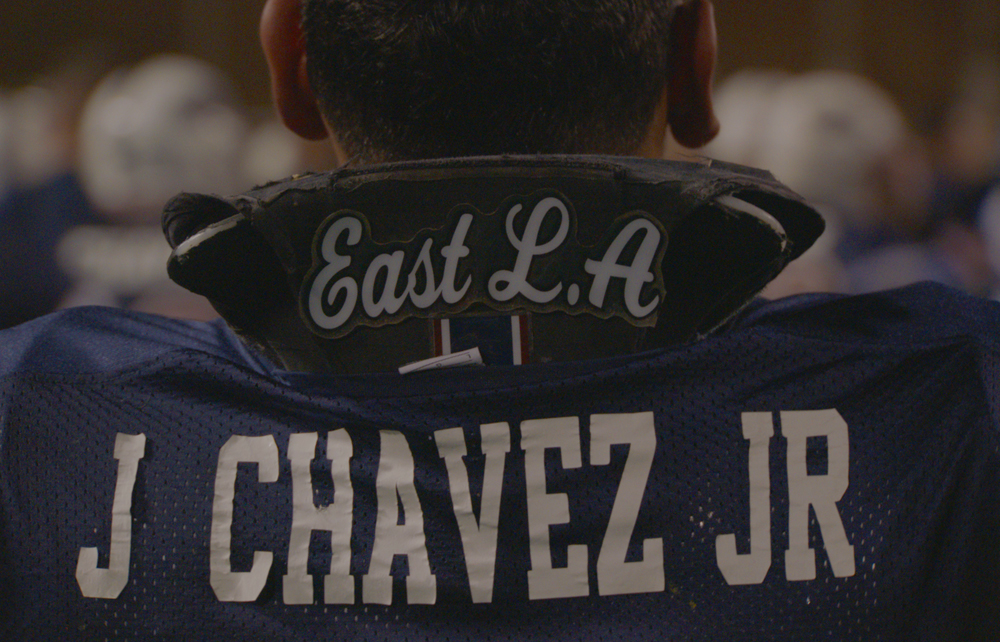

To do so, “The All-Americans” ups the ante by training its lens on subjects who are just looking to find their place in general, storming the halls of Garfield and Roosevelt High, which sit less than five miles away from each other on opposite sides of Whittier Boulevard. Empathetic as the film may be, McMillin quickly establishes that there is no love lost between the rival high schools, at least when it comes to football, and their annual showdown at the end of the season regularly tops 20,000 in attendance. Yet through charting a season in the lives for the Roosevelt Rough Riders and the Garfield Bulldogs from varsity tryouts to the big game, “The Classic” observes young men who not only have the sport in common, but the necessity to grow up far quicker than they should at their age, often having to make up for parents who are largely absent from their lives either because they’re hard at work putting food on the table or are no longer with the family for less noble reasons. In the Classic, these teenagers are allowed an all-too-rare celebration of their talent, as well as — in the game’s 80th year — one of the few institutions they can lean on and call their own.

Having established himself as a premier editor of documentaries such as “Meet the Patels,” “The Short Game” and “West of Memphis,” McMillin ably balances out a number of compelling storylines building up to the titular event to the point they explode off the screen. With the film arriving in theaters, the filmmaker spoke about his feature directorial debut, how listening to the radio inspired the film and making sure that the big game got its due cinematically.

How did this come about?

I live on the West Side and I was coming home from my office in Venice and heard a tiny little news story [saying], “Tonight, there’s the annual East L.A. Classic. The attendance of tonight’s game is expected to be 20,000, a capacity crowd,” and that was it. These guys [on the radio] moved on and went to the next story, but there was this outlandish number. I’ve been in Los Angeles for a long time now and know nothing about East L.A., which is embarrassing, [but I wondered] how do they get 20,000-plus to come out to a game? That’s ridiculous. I wanted to cover immigration because I had seen it rising as an issue for a long time, where people [increasingly] were in their camps and weren’t talking in a way that made any headway, and this [seemed like] an avenue in to look at America as it was changing and try to tackle [the subject of immigration] in a way that welcomed people as opposed to just tell people in a dogmatic way.

Did your background in editing help this come together?

Having a background as an editor is both a blessing and a curse because you think you’re going to approach it very strategically and treat all of [your footage] as a cog in getting towards your end message, and what ends up happening is when I’m editing, I only know the actual people that exist on camera, so I’m divorced from the actual people. When you then have to put yourself out in the field and growing relationships with these people and…my God, [my subjects were] high school kids. They are the most unreliable people on the planet. [laughs] They’re the hardest to corral and in East L.A., half of these kids didn’t have cell phones, so it was really hard to get in contact with them. Some of them didn’t live at home. Some of them were homeless at times. So it was a real challenge of trying to get the material and try to stay on point.

How did you gravitate towards the kids you did?

First, I was introduced to about 20 different kids by the individual coaches. I met with Coach Cid and Coach Hernandez and they ran through what they knew about the kids on their team — and it’s surprising what these kids share with the coaches. I wanted to have a diverse cross-section of kids that I followed and I started interviewing the kid and I ended up following about eight in total. It’s tricky in a normal situation trying to pare down your characters, so this was particularly hard because I had two teams and there’s not a good team and a bad team. You’re not rooting for one over the other. You’re supposed to be rooting for these individuals and I wanted to make all these characters compelling and have their own issues to deal with, so [it involved] breaking down the kids that are not as what you would expect.

Mario, one of my kids on Roosevelt, has almost a perfect grade point average and comes from a mixed-status family — some of his family are undocumented immigrants, and most of the family has been here for 15, 20 years or more, but they have a very questionable status — but this is a kid who has bucked all of those trends [associated with immigrants] and wants to create a great future for himself. Then you cross that with Joseph on [Garfield], who is a very hard knocks kid, and has much less parental support [with] a father who basically spent Joseph’s entire childhood in gangs and he’s been in and out of prison, and his mother was addicted to drugs and never around. So he ends up being raised by his grandmother and has to grow up at a very, very young age. Consequently, he has a child at a young age and has to deal with that responsibility.

I also wanted to have kids that you would perceive as All-American kids in this Latino immigrant population [setting]. The nice part about [contemporary] East L.A. is that this is the first group of immigrants that have come through that region that are really starting to put down roots and starting to make that their home as opposed to starting as immigrants there and then moving on, so I had a number of kids that fit that mold. And then lastly, I chose Stevie [an African-American transfer student on Garfield] because he was an instrumental part of the team, but also it created internal dynamics of team conflict and neighborhood conflict with somebody from the outside, [in effect being] a reverse immigration path where he’s dealing with being the outsider and them questioning his legitimacy of being here.

Since the coaches were the entry point for you, it seems like such a gift that they had such distinctly different attitudes towards their jobs, team-building and everything else. Did that set the tone for how to tell this?

Yeah, that’s not dramatized at all. They are remarkably different in their approaches, their personalities, the structure of their teams. We always referred to Garfield as the machine. Everything was run with military precision and [Coach Lorenzo Hernandez] is a loving coach who really wants those kids to succeed on all levels, but he’s tough on them whereas with Coach [Javier] Cid [at Roosevelt], I have scenes [where] you would have 50 kids reviewing game tapes, lying around on the floor with blankets on and it looks like this big family room, so it’s a really different approach. Coach Hernandez is much more driven to win and Coach Cid, at least from what we saw was more geared towards making sure that the kids within his program graduated and that he gave the kids within the neighborhood the opportunity.

Remarkably, the film feels as intimate on the football field as it does when you’re at the kids’ homes, though it gets so much bigger at the end. Was it challenging to keep the camerawork consistent throughout?

It was a challenge definitely at the football games. The kids and their families were remarkably welcoming and for the most part, it was just myself shooting and doing sound or myself and my [director of photography] Ann Rosencrans. We maintained it being incredibly small because I wanted the kids to connect with me and it helped that we were doing everything ourselves [because] it helped the kids open up and not feel we were some sort of invading force.

For the end game, we expanded out [the crew] 10, 15-fold. I think we had 10 primary cameras that were roving and then wirecam and additional cameras. We had 14 players and six coaches mic’d. We had five sound men and boom operators all around. It was a 22-hour day that we worked, and I got to Sammy’s house at 5 a.m. and didn’t stop shooting until they wrapped their party at about 1 or 2 in the morning. So it was a big difference. Also, we brought in a few guys who were really good NFL Films cinematographers to bolster us as camera operators on our coverage of that game who could actually get these intense shots to try to make what most people don’t see, which is a high school football game done larger than life.

The game really explodes onscreen.

That’s the nature of the Classic itself. That game, for all intents and purposes, is a regular season high school football game, but these kids in the community make it into an event. It’s a time for these kids that’s their moment to shine — their moment to be larger than life — so we wanted to depict it in that way.

Since you filmed through the end of the school year in 2016, you were probably editing around the time of the presidential election. Did the national conversation around immigration influence how you might’ve wanted to shape this?

It certainly influenced made it more urgent to deal with. I had hoped that conversation would be shifting to a more rational perspective [by now]. I fear that we’re at a point where it’s only getting more polarized and my hope is that a film like this that doesn’t demonize one side or the other, but actually shows these kids as Americans, as people that are worthwhile, and we’re showing people going through the struggles of their lives in a real light, but also showing them having the same aspirations as anybody else, so that it actually does good as opposed to make people angry.

Was making a feature what you thought it would be?

It was a lot harder than I thought it was going to be, but I think most directors would probably say that. Having been an editor for so long and having gone through hours and hours of footage from directors and just swearing at them going why didn’t you get this or you know whatever, and then having the reality of that situation come to term, it was definitely humbling. But I enjoyed it immensely. I like so much more being out in the field and actually getting to invest in people’s lives. It’s incredibly rewarding. I think that’s the only way that we get at those bigger issues that are paramount in the national conversation is to get at the truth in telling individual people’s stories.

“The All-Americans” opens in theaters on November 8th. A full list of theaters and dates is here.