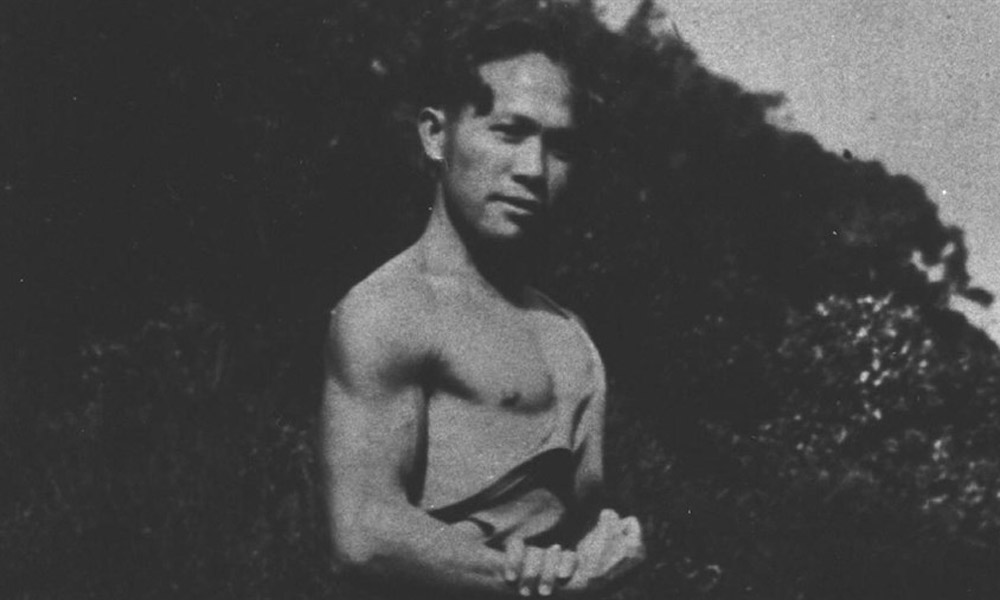

Sometimes when it comes to impressive documentary access, all you need is one person and in the case of “Cane Fire,” that person is director Anthony Banua-Simon’s great uncle Henry Bermoy, who has been around long enough in Kauai to see the Hawaiian island’s primary industry shift from sugar to the tourism business. Bermoy, whose descendants had worked in the cane fields as immigrants from the Philippines and grew into a leader for the local union when he was a trucker for the pineapple canners, witnessed first hand how the small group of business titans that controlled the island’s economy pivoted when Hawaii achieved statehood in 1959, recasting it as a resort town just as those that worked in sugar had finally organized to give themselves greater collective bargaining power and were thrown back down the ladder into the hospitality industry where pay was less and all the work that went into unionizing would have to be done all over again.

Banua-Simon slyly takes the title for his film from the abandoned one for another, Lois Weber’s “White Heat,” a 1934 drama set on Kauai that had run into problems with the ratings board for its ending, depicting a workers rebellion in the plantation, and as “Cane Fire” fascinatingly comes to illustrate, the eventual compromises to Weber’s work were only the start of whitewashing Kauai after Hollywood was enlisted in burnishing the island’s image as a vacation destination. Weber’s film is now thought to be lost to time, but Banua-Simon shows its enduring power and that of the medium as a whole for better and worse, presenting clips from 1950s films such as the John Wayne starrer “Big Jim McClain” and “Jungle Heat,” which were part of a rebranding of Hawaii where studios could gain access to extraordinary locations if they worked with the land owners on messaging about both the beautiful sights tourists could come see and ugly labor situation involving the locals, likening efforts to unionize with communism and violence.

There is a slightly scattershot quality to “Cane Fire” as the director uneasily weaves together something of a personal essay, archival doc and verite footage of an occupation at Coco Palms Hotel, a once-popular location for productions such as “Fantasy Island” and “Blue Hawaii” that was destroyed in a hurricane and now subject to a land battle between redevelopers and a group of locals insisting it belongs to them. But then again, the film has a lot of ground to cover and while Banua-Simon leans heavily on narration to bring the disparate threads together, he impressively takes up the challenge of demonstrating how little has changed from the days when protestant missionaries saw the opportunity to exploit Hawaiian natives and bring in immigrants to work in the cane fields essentially as indentured servants while they prospered to the present day where locals are groomed from birth to work in the resorts, owned by the same dynasties that ran the plantations, and prevented from earning wages that would keep up with the ever-rising cost of living.

After pointing out that Hollywood often took advantage of the locals as well, hiring them to appear as extras in films where they could lend their credibility to projects that projected one way for the world to see them, “Cane Fire” offers an overdue corrective by making them the stars and it turns out they have a far more compelling story to tell than what’s come before.

“Cane Fire” will premiere virtually at Hot Docs, where it will be made available to Ontario audiences from May 28th through June 6th.