It is rather perfect that the centerpiece of Alina Skrzeszewska’s “Game Girls” is a wedding since so much of the film is devoted to capturing the frenzy of life on L.A.’s Skid Row, where rituals of society at large remain something to strive towards even though its citizens have found themselves on the outside of it, largely because of misfortune or by a vicious cycle that started before birth. While expressing this doesn’t come easily to the women Skrzeszewska follows in “Game Girls,” the director found a novel way into the subject by working with Dr. Mimi Savage, an expert in drama therapy, to offer workshops where they could unburden themselves with the help of toy figurines that could distance themselves from the direct experience of the trauma they’ve experienced on the streets.

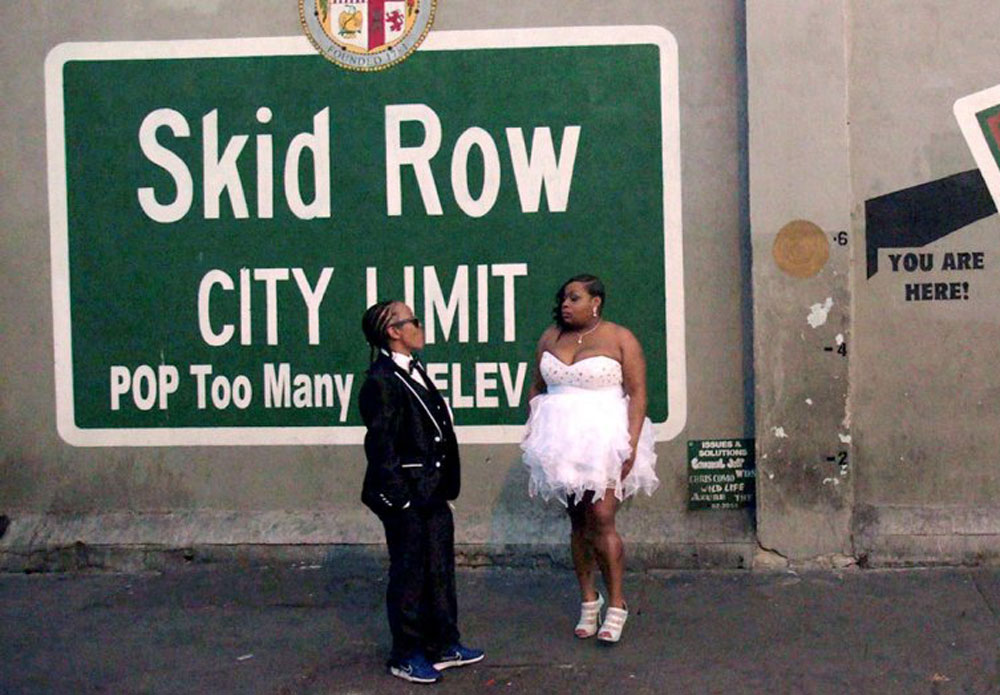

Over the course of three-and-a-half years of filming, Skrzeszewska collected footage from these sessions and equally crucial, scenes of the women’s indefatigable resolve to build a life in spite of such mental hurdles in addition to practical systemic ones, gravitating in particular towards Terri Rogers, an irascible and tenacious woman living on the same streets that her grandfather once did, yet radiating a self-confidence and positivity that would seem to be at odds with her circumstances. While finding joy is something Terri’s predisposed to, she’s especially giddy on the day she’s set to wed Tiahna Vince, who is likely responsible for some of the bounce in her step, but it was exhausting for Skrzeszewska, who spent the entirety of that Valentine’s Day lugging around a camera as Terri, an eager groom, becomes impatient while waiting on her bride who takes far longer to prepare.

I made a previous documentary feature, “Songs from the Nickel” that came out in 2010 that I had been living on Skid Row in order to do, but also just because I was interested in it and it was an experience I wanted to have. It was a cheap place to live and I didn’t have money at the time, so I was in an SRO hotel, the King Edward, for almost two years, and when I started filming there, I was basically filming with my neighbors. There were like three women total living in the building and the rest were all men, so the film ended up being very male-dominated and I wanted to do something about women, but it took me a while to figure out how I was going to do that because the women’s stories seemed a lot more complicated to capture authentically.

I really wanted to avoid tapping into the victim’s story [you hear so often] and that happens really quickly with women on Skid Row because it is a very, very rough environment. I also didn’t want to frame them in a way that would be defined by being quirky. I wanted a fuller, more authentic representation, so that’s why I came up with this idea of creating workshops where I would essentially co-create something with women on Skid Row. I didn’t really know what would happen in those workshops, and I didn’t have Mimi, the facilitator, [yet] – and I realized quickly I couldn’t be the one facilitating it because I don’t have that skill. But then I found out about drama therapy and I felt like wow, this is everything I’d been imagining – there is a name for it, there’s a discipline that does that. So I started looking for somebody who could be that person and luckily, I found Mimi. It was a great match and we did these workshops for close to two years, and that’s how we met Terri. I thought initially it was going to be a little bit more of a collective portrait, so I started shooting multiple women and Terri was one of them and as time progressed, her story started taking over more and more.

I should also say on my first documentary, I was working with William Shepherd, who’s a story adviser who lived across the street from me at another SRO hotel, and we’d be seeing these women, really young ones, who were acting really, really rough on the street. They were like 16 years old and would beat up grown men on Skid Row, so we kind of wanted to know who they were and there’s a couple of those groups, but Tiahna was part of one of them.

But I knew I wanted [a relationship] in the film. At some point, I thought maybe it was going to be a mother/daughter story because I knew I had some of those, but those didn’t kind of pan out quite the way I was hoping for, and I knew there needed to be love and emotion because when you talk about Skid Row, people don’t think about the relationships that people have – they have romantic relationships, they have family and they’re living lives just like everybody else. Also, they’re funny. I wanted to make a film about trauma, but even though it’s really, really tough stuff, the way they handle it is with a lot of humor, so I wanted to bring that into the film. I didn’t want it to be so serious and play into this idea of trauma victims.

This may not be what you’re referring to, but it was eye-opening to me at the screening to hear laughter coming from the area of the theater Terri and Tiahna and their friends as you show a pretty violent domestic dispute between them. Was that dissonance there in the making of it?

Honestly, I was surprised about that too, and I think there was a lot of nervous energy there too because it is heavy and everybody knows it’s heavy and it’s real. They’ve witnessed it. Humor is a survival mechanism and [they laugh] because people recognize it there and their friends recognize it. But it is traumatic and it is very rough for them at that moment and for all of us being there, so in order to not be stuck in it, it is one of the mechanisms to laugh.

There was another thing that’s referred to [in the film] when their dog jumped off the roof of my studio downtown, which was a five-story building. It was another one of those things where it was horrifying and so sad and Terri was crying, but then she started making jokes about it in the middle of it about how the dog committed suicide. There was stuff like that where it’s finding comedy in tragedy and you have to have that, otherwise you can’t go forward in that tough an environment. It was this surreal Skid Row humor that you will find if you hang out there. That’s one of the ways people deal with it.

That was really on the spur of the moment because making a film on Skid Row really requires that you just go where things are happening because usually things just randomly happen. I would find out about something, but mostly Terri would call me and say, “Hey, come on down, I’m doing this or that right now.” Then I have to just get my stuff together and see if anyone was available and often times no one else was. Sometimes I’d schedule things with them, but there were a lot of times when that didn’t work out and it would’ve been impossible to do this with a schedule that involved a big crew and set up time because every time I’d have somebody with me – a sound person [for instance], it was [always] after they left when the interesting things would happen.

After hearing your way into the film was through setting up these workshops, it was surprising in retrospect that you decided not to include yourself or Dr. Mimi in an on-screen role. Was it much of a decision to exclude yourselves from the narrative?

That was pretty clear for me from the beginning [because] I wanted it to play more like a verite narrative, and in terms of excluding Mimi visually, I really didn’t want to make a workshop film [where] usually the facilitator/the leader of the workshop really becomes the lead character. I wanted to make it very, very clear that the perspective is from whichever women we’re following, so it really doesn’t have this top-down [feeling] or savior narrative in it. It was really for me to show the resiliency and the skill that they had and was not dependent on anybody else, so that’s why I thought that why that wasn’t necessary. We do have [Mimi’s] voice, so we do feel her presence, but I really didn’t want that to take over the story.

You actually test screened your film for the women in the workshop. What perspective did that bring?

I showed the core group a previous edit that was very, very different and went off [to do the final edit based on] that, but throughout the whole process of the workshops, I would ask people what was really relevant to show about Skid Row or we’d have certain thematic sessions where it was about getting ideas or feedback or brainstorming around certain themes that I thought would be important and just seeing are they really? That’s how I found allocated the importance to the different elements in the film, by having confirmed by this chorus in a way, so even though most of the women in the workshop, for example, weren’t gay, still the important elements of their experience, including childhood stuff, really resonated with [Terri and Tiahna’s] story in the film and through this individual story, I really felt I had a groundwork to tell this larger story.

Really, really great. We premiered in Berlin and we had all sold out screenings because it’s such a great audience festival, but it’s yet a different thing to be showing it here at Outfest in L.A. and with people from the community who came out because the film resonates in a deeper way. It’s a really different experience to see it with an audience versus alone. Some audiences, like when I see it in the U.K., feel a little bit uncomfortable laughing because the film is intense and I guess I forget how intense the film is – or I had forgotten when I was making it or finishing the edit. I’m immersed in the kind of Skid Row humor, so I forget that for an audience sometimes, they’re not able to get there as easily unless there’s somebody there that can open it up for them. I think the humor is really essential [to disarming an audience], so it was really, really great to see that [in L.A.] and to see the film does resonate with audiences and with the community where it came from. But I just want it to get out there more and to be seen. my hope is we can do a community screening campaign where we go to different communities and there’s a workshop element as well [that would be] a small, replicable module of what we did in the workshop here that someone else can facilitate, and that ideally, one of the women who participated in the workshops [in L.A.] could fulfill it. Whether that’s Terri or one of the other women, that would be the best way to see the film.

“Game Girls” shows once more at Outfest L.A. on July 22nd at 1:45 pm at Regal L.A. Live.