Vicky Du had a different issue than most with getting access for her debut documentary feature “Light of the Setting Sun” when her own family was naturally willing to speak to her about a most personal subject, yet what exactly that was could be hard to describe. Du’s brother had had a debilitating anxiety attack that he found difficult to trace back to anything in particular, though memories that had surfaced from considering possible culprits led to remembering his childhood a little less charitably than it had long lived in his mind, with his mother having an anger streak that both of her children could only partly intuit when they were younger when all the curse words were in Mandarin as they grew up in New Jersey. As the filmmaker notes in the documentary, why Du and her brother were the first generation of their family to be born in America while their parents had been the first to be born in Taiwan, separated from generations of their bloodline that had grown up in mainland China had long been a mystery to them, understood only in fragments as the family in general had scattered across the world with each member holding a piece and not necessarily able to share as they started to lose contact with one another. Du saw it as her responsibility now to pull the pieces back together, if only to get at the root of what ailed her brother.

Although “Light of the Setting Sun” tells the story of just one family, it takes on far greater proportion when it exposes the reverberations of exile as Du learns that her family was forced to flee their homeland at the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. The fractures are geographically evident when Du visits her uncle and grandmother in Taiwan on the occasion of her cousin Dupi’s wedding, a trip that it’s been virtually impossible for her own mother to make due to the fraught memories that it holds, but the filmmaker is able to elucidate the psychological fissures that have plagued the entire family ever since being separated by forces beyond their control, acting more coarsely towards one another when they had to be so concerned for their own individual survival and casually abusive behavior became normalized when they couldn’t expect more of themselves than how they had been treated by the rest of the world. Ultimately powerful enough to likely break a cycle, the film is also quite delicate as Du gently coaxes family members to recall things they’ve either blocked out from pain or simply not having enough context to understand, eventually facilitating a conversation across continents and time made possible by film.

A year after the film premiered at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival in Durham, “Light of the Setting Sun” is starting out its broader release with a weeklong theatrical run at the DCTV Firehouse in New York, followed by a Los Angeles premiere at the Asian Pacific Film Festival on May 4th and eventually a broadcast on PBS’ Independent Lens later this year. Du graciously took the time to talk about connecting the dots over the years to bring healing to her family and tell a story that so many can relate to in a day and age, as well as literally giving it a personal touch.

It’s a very personal film, really spurred on because my brother had this mental breakdown, and much credit to my mom, she actually organized for all of us to go to family therapy together and in these sessions, a really common exercise we’d do was a family tree exercise. The whole point was to show that [the trauma] didn’t start with the individual who we’re looking at, which is my brother. We wrote out the tree with my grandparents who had fled China from the Chinese Civil War and then I had all my aunts and uncles and my cousins, and the therapist asked us to mark an X over every person who experienced either mental illness or some type of trauma or domestic violence. We actually ended up marking an X over nearly every single person, so this idea we had inherited something, and that the trauma had spread despite time and place really compelled me. I wanted to understand how the effects of the Chinese Civil War were still affecting us.

Obviously, your family was ultimately supportive of you because of their participation in the film, but you can tell they’re uncomfortable going back into the past. What was it like making the decision you were going to take everyone back to this painful past?

Every decision and everyone’s feelings around it changed and shifted over time. My immediate family was very supportive of the film and the story behind it, and they felt like it was very important. Everyone agreed to be interviewed. And in those interviews, it was really important to me that I ask these very difficult questions. Then I feel the real reckoning was when they got their eyes on the fine cut because they were seeing how all came together in my point of view and the exact story I’m telling and how I’m using their voice. That also took some time for them to fully digest the process.

I thought [initially] you can just like ask a question and you’ll get an answer. That’s not really how it works, especially if I want two people to speak to each other. That’s even harder. So what I found was I would create conversations or what I felt like was a response, maybe the next day with a different [person] to what someone said yesterday and put them right next to each other to try to create these types of conversation. And a lot of the credit goes to the editor Tara Long, who really thought to focus on a natural line. So my mother’s mother, who has passed away, and my paternal grandmother, my dad’s mother, spiritually play a very big role in the film and the biggest thing there was just losing family members [from the story]. I had filmed with an entire branch in Toronto who ultimately didn’t make it in and family members who are living in China now. [Tara] really honed it in on [this part of] the family tree.

Was there anything that happened that you may not have expected, but took this in a direction you could get excited about?

We filmed so many things that we didn’t know how they would turn out. The biggest is probably the trip with my mom to Taiwan. I had no expectation of what would happen. In the film, we visit my grandmother’s memorial site where her ashes are packed. My mom had never been there, and I wanted to capture whatever would happen, but I didn’t know exactly what that would look like. And conversations with my family — my grandmother, and asking my brother about his mental breakdown, which was the first time I had done that — all of these things, I didn’t know what exactly would happen, but we filmed it and ultimately it became a big piece of film.

That came about because he actually invited me to be [part of the wedding party]. And I was just so moved by that because we had only met a few times prior. We didn’t meet until we were adults. And I felt this kinship of family where even if you don’t talk for decades, you still have this familial closeness, [which] I thought was also so representative of what the film meant, so I wanted to capture that scene.

It struck me that a lot of the physical material for this, such as the memory book or pictures, that you may have already had in your possession took on new meaning as you were either having it translated or new information was coming to light from your interviews. What was the process of discovering meaning there?

I had known about the book, that was very significant to me when I was in university, but the biggest thing was the letter [that was unearthed during production]. A member of our family who survived being in the labor camps in China during the civil war and cultural revolution had written a letter to my grandfather and my aunt had mailed this letter to me unexpectedly. And as I detail in the film, I had a feeling that this is what my family went through, but I wasn’t positive because no one had ever spoken about it and my parents had no understanding. So I didn’t know that’s what happened and that letter really blew me away. That had to be translated, first by my cousin and then later by [a professional] translator and I think it just gave my family a sense of historical context and identity that I had never had before. That was also so deeply impactful, and of course traumatizing [as well], but it was written in such a personal way, it felt like such a personal piece of history.

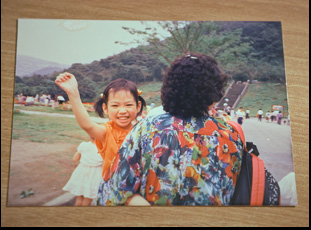

That was also a big teamwork effort with Tara Long, and I had written the narration, but she really shaped that it would happen and what we could talk about the subjects in a way that I was unsure of, but she could see it. And then similarly with the photographs, she was just encouraging me to get archival — photos or anything [else] — and something I love to do when I go home is just like thumb through old photo albums. And so over two days, I just placed the camera right above [myself doing that].

This is quite something to carry around with you. What’s it been like to get off your shoulders and out into the world?

It’s totally wild because the process itself was really hard and emotionally taxing. Of course, having my family watch it and ultimately sign off on it was also really hard, but then also releasing a film is so hard, so you’re doing those things at the same time and both those weights are being lifted at different moments. But I’m excited because we’re doing the New York theatrical run this week and then a PBS Independent lens broadcast in the fall, so I’m really excited to hear how people react to it once they see it.

And [New York] will actually be the first time my mom will come out to a screening and participate in a Q & A, [which] will be the first time that I watch it with another participant. We wanted my family members to be okay with what the material that ended up in the film, [so we showed it to them] but that was through links. I also want to bring [the film] to Taiwan and I think that will be another really interesting part of the journey — for them to be able to see how other people react to the film.

“Light of the Setting Sun” opens on April 18th in New York for a weeklong run at the DCTV Firehouse with Q & As to follow the 7 pm screening daily. It will next screen in Los Angeles as part of the Asian Pacific Film Festival on May 4th at 12:45 pm at the AMC Atlantic Times Square 14.