With a voice as majestic as Maria Callas’, ensuring that it came across as pure and powerful as in any great opera hall around the world was a challenge that “Maria By Callas” director Tom Volf compared to mountain climbing.

“It was like climbing Mount Everest,” laughs Volf, describing what went into the documentary’s precise sound design, making Callas’ performances from the 1940s and ‘50s from often scratchy recordings sound as if you were hearing them for the first time. “To make it harmonious again, to make it accessible and easy to listen for everyone, it was a big challenge. But I think we made it.”

It wasn’t just Callas’ timbre on stage Volf had to get right, but finding clarity off of it as well in allowing the legendary soprano to speak in her own words about her life in “Maria By Callas.” Told entirely with interviews she had given and letters she had written (given voice by the contemporary opera great Joyce DiDonato), the film traces Callas’ rise from a young girl in New York who left for Greece just after high school, complimented at the time by her teachers for having “a large mouth, expressive eyes and a crazy work ethic” that put her on the fast track to become a star at the Conservatory of Athens. But in becoming a force of nature who could get people to line up in the snow to see her perform, she endured plenty of turbulence, from burnishing her reputation as a diva when she walked out midway through a performance of Bellini’s “Norma” in Rome, claiming her voice had given out, with the president of Italy in the audience, to a much-publicized romance with shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis, who would come to leave her for Jacqueline Kennedy.

In restricting himself to Callas’ own thoughts and recollections, Volf burrows deep to get at a rich inner life that shaped her music, the uncertainty at times and the bravado at others that could give so much emotion to her performances but she often left unarticulated otherwise publicly, and beyond how illuminating it is to have her own voice describing her experience, “Maria By Callas” renders her life’s journey quite vividly with rare home movies from her travels around the world, childhood photos and footage from her performances that burst with vitality from being lovingly restored. Shortly before the film arrives in theaters, Volf spoke about the four-year process in which he came around from being an opera novice to keen aficionado and doing justice to his larger-than-life subject.

We can say by accident or with Maria Callas, we can say by destiny. [laughs] Five years ago, I was living in New York and one night, I was just walking by the Met Opera and I stepped in, not knowing what I was going to watch. I really fell in love with Italian opera that night, with Donizetti and Joyce DiDonato singing and I fell in love with everything – the artform, the expression, the singing, the music. So I came back to my little apartment [that I shared with a roommate] in New York – I was a very standard student, and started to look up “Bel Canto” and Donizetti and the first thing that came up was an aria sung by Callas. That was a true revelation. It was the beginning of it all.

You set yourself such a challenge to take on her perspective and words – was that central to the project from the start?

Very early on. In the very beginning, the first year I spent on a quest to find who were her friends and loved ones who were still alive around the world. I interviewed them all and they all gave me a lot of material that is also in the film today – archives and personal material, documents, private Super 8 films and recordings. And then after that year, I really came to realize that the most genuine and accurate way to tell her story would be to have her tell her own story herself. So I decided to put away everything I had filmed myself and to make the film stand a hundred percent on archival material [with] only her being the narrator of her life story. That was a breakthrough, but I had to change everything and start from scratch to make this happen.

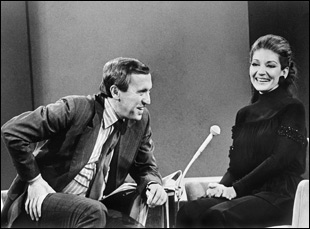

This interview is very special because it only aired once in 1970 and it was considered to be completely lost, and also because the way she speaks is very different than any other interview. It’s almost like it’s not an interview, but a confession. Very naturally, it came to become the thread of the film, almost like the film was a flashback of her whole life from that interview where she looks back and she was able to reveal things about herself that she never revealed before or after to anyone else, so it’s really special.

In order to make a film like this, do you have to have all the pieces ready before you start assembling or could you discover things in the process and put them in?

It’s a process that evolved over four years and there was no way I would know the time I would spend on this, the work, the effort to get the material together. Part of gathering all those pieces was research because a lot of the material in the film was considered to be lost or completely unknown. The whole film is made of precious gems, things that were unseen. The opening of the film, which is her singing “Madame Butterfly” in Chicago in ’55, is an amazing piece of footage that nobody knew about and she only sang this part once in 1955 and there were only three or four performances, so it just gives you a sense of how precious it is to watch quite a bit of it.

And then the second stage was to put this puzzle together and to make sense of it and to make a story out of it. The editing of the film was over six months long and throughout the editing, we were still getting some of the clips and some of the things, like the bottles in the sea that I had thrown months before. Of course, I did have a foundation for the main story, but part of the film also emerged from the material because some of the material, for example some of the letters, revealed things that I had no idea about and all of these layers came from the material.

She was an inspiration for the film to begin with because that night when I walked to the Met in January 2013, she was the one singing and made me understand the influence of an artist like Maria Callas on new generations. Joyce, to me, is part of that lineage that Callas started or even gave birth to, so I was very lucky to get to meet with her a few months later and become friends. When the letters came about, I knew they would need to be an important part of the narration of the film because all of these words have actually been written by her, but I needed a voice to bring the words back to life. They’re the most intimate revelations from Maria the woman and give that layer of depth in the story, so it was absolutely obvious that it should be Joyce because she would be able to actually voice those words that Maria wrote in a way that is not spoken, but she actually lived because as an artist and as a woman, she can really relate to what Callas was going through. I like to think that towards the end of the film, we don’t really notice the two voices. It actually is one voice. It is the voice of Callas.

It sounds like you may not have had all the letters at the start. Were those something that came along later?

Actually, I had a few at the beginning, but they kept coming in slowly from the various people – her friends and all the research I had to do in the archives, private and institutional, all around the world. It took a lot of time to get the material and of course, I ended up having much more letters than I was able to use in the film, but we really used the most striking and moving ones in the film.

What’s it like coming across a piece of footage like the backstage footage in Trieste?

Incredible. Because imagine this is just a thin 8mm reel that miraculously survived nearly 60 years, and the gems in the film are to see her not in stills, but actual movies – home movies and private movies, showing her as we have never seen her before. In the example of the Trieste, it was one of her first Normas. She was still not famous. She was still going in the provincial Italian theaters and she was not the figure that we all know today, so it’s very moving to see her like that and then to see how it evolves in the film.

It was very natural. There was a variety of [film] formats, so there was a lot of work to restore and also harmonize all those formats, to make it into one story. But at the same time, I wanted to get a chance to show the particularity of this material because Super 8 nowadays, it’s very hard for us to get a sense of what it was. We all have phones and we can film a limited amount, but in these days, it was just these thin layers of reel tape where you could only film up to three minutes. So I wanted to show that fragility, and also, it’s of all those private moments, so you see that it was not professionally filmed. It’s literally coming from her friends or her own private films and I wanted to give the audience a sense of what this material was.

I was struck by how vibrant the colors were – what shape were the materials in when you found them? Did you have to do anything to bring that feeling out of it?

It depended. We had some material that was miraculously well-preserved and some material that wasn’t, so we really had to do a lot of work to bring it out in the best possible condition. This is the first time that all this material is shown in high definition, so I think that gives us the feeling that this is not old footage. I was quite surprised myself that a lot of this material was originally in color and the way it was filmed is so striking and so vivid, I really enjoyed it myself, so I enjoyed bringing it out for the audience in those ways. But there’s nothing artificial. Everything is really authentic.

One of the interesting choices you make is including her music, but not showing actual footage where she’s on the screen singing until a quarter of the way through the film, which creates a big emotional moment. What was it like figuring that out?

There was a rhythm that I wanted to find to make the film pretty balanced in terms of the Maria part and the Callas part – the personal part and the artist part. So I tried to find this balance [where it wasn’t a] completely musical film that would only appeal to opera lovers, but very accessible to people who like myself five years ago weren’t really into opera and who can get a sense of it and maybe discover opera through the film. And the performances in the film give you a whole subtext that tell you things about her as a woman through the artist singing [which] is why the film is “Maria By Callas” because it’s Callas who reveals Maria in the film.

It’s really beautiful. It’s very unexpected because I never would’ve thought while I was making it that it would be out in 40 countries and that I’d be so privileged to travel with it and it’s interesting because she traveled in all those countries in her lifetime and I noticed that each country and each culture has their own relationship with her. It’s a little bit different everywhere, which I appreciate a lot because for instance, in Greece, they relate to the fact she was of Greek origin. In Italy, they relate to the fact that the greatest years of her career were in Italy, and then in America, it’s very much the fact that she was American born and as she says in the film, she was born in New York and is rather proud of it, so it’s interesting for me to relate to all those aspects because in the end, they all make a complete picture. And I’m moved by the common thread throughout the countries and cultures – and also the ages – of the audiences that come to see the film is they all relate to her as a human being. She was such a universal character and artist that she can speak to everyone, so that’s been the most gratifying, and it’s a real privilege to be able to bring her to audiences in theaters worldwide.

“Maria By Callas” opens on November 2nd in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal and New York at the Angelika and Paris Theaters. A full list of theaters and dates is here.