There were other storms to weather in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan, the terrifying monsoon that swamped the Philippines and took the lives of thousands and crippled the country’s infrastructure. However, as generally happens with such natural disasters, the immediate international attention and aid that flowed into the country waned over time as people still grappled with incalculable loss, not only of loved ones but the lives they led before everything changed. Seán Devlin knew the calvary wasn’t in it for the long haul, but the Filipino-Canadian filmmaker understood that even operating alone, there was a way to show that the outside world hadn’t forgotten them, making a series of films in collaboration with communities that were affected in which the time he spent on the ground would make up for the fact that he couldn’t bring much of a crew besides himself.

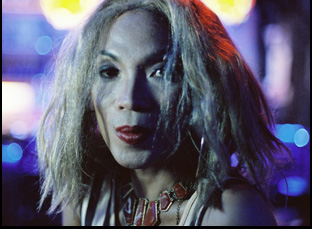

Starting out as a comedian, Devlin is used to keeping things light and “Asog,” his second feature from Leyte Island where his mother was born, may reference the burden that Filipinos have had to bear in rebuilding their lives since 2013 and subsequent climate catastrophes, but it actively feels as if it’s lifting it for both the people on screen and off as it follows Jaya and Arnel, two residents of Tacloban City who become friends when there is quite literally little else to lean on, helping each other move forward as they lament the lives they were on track to having. While Jaya was once a TV personality who now sees a nightclub as an outlet to entertain others, Arnel is now pressed even deeper into duty running errands for his family after starting to imagine what he might do on his own once he was old enough. Eventually, having to lay these thoughts of what could’ve been to rest proves to be an opportunity to radically reinvent themselves, but it’s hardly a straight path to get there, making the windy road the two take to Sicogon Island, where hundreds of displaced families remain in protest of developers moving into claim the land, a fair reflection of what they’re both feeling inside.

The path to “Asog” was similarly indirect for Devlin as the stories he’s told out of the Philippines have gradually moved further away from the explicitly documentary approach he initially took in his first dispatch from the islands, the 2015 short “Dear Pope: A Letter from Typhoon Haiyan Survivors,” in which he embedded with the Pablo family from which “Asog” star Arnel hails. Allowing survivors of the typhoon the dramatic license to express themselves in increasingly fictional scenarios has led to an exorcism of sorts as nonprofessional casts have processed genuine emotions on screen as they did in “When the Storm Fades,” Devlin’s first stab at a feature with a narrative thrust, and ironically, while “Asog,” which invokes Filipino folklore and madcap comedy when Arnel and Jaya make for an entertaining odd couple, is the director’s most overtly fictional film yet, it is the one that has already had the greatest real world consequences after shining a light on the land grab taking place in Sicogon Island where a real estate developer was prompted to pay reparations to families that had lost homes in the typhoon but not the rights to the underlying property that was redesignated for a luxury hotel following the film’s premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival.

After a celebrated festival run, “Asog” is now available far and wide on VOD and digital and Devlin graciously took the time to talk about how his approach to filmmaking has changed over the years, capturing the Philippines as he’s experienced it firsthand and stretching the production across the pandemic when borders closed and seeing the film through to the very end.

I was born and raised in Canada, but my mom is from Leyte Island in the Philippines where Typhoon Haiyan caused all this devastation. My own cousin in the Philippines lost her home a few years before that in a different typhoon, so it definitely starts from a family connection and a desire to do some work over there. I had a mentor who described responsibility to me as your unique ability to respond to a situation and I’m a stand-up comedian. I’ve also been making films and videos since I was a teenager, so comedy and film is just my unique ability and I thought, “What can I do over there to bring attention and work with folks experiencing these disasters that can hopefully improve conditions? These films are the result of all of that. “Asog” is actually my second feature in Leyte and my third film since 2014 when I did a short documentary on the one-year anniversary of Super Typhoon Haiyan.

The origin of “Asog” is when I was doing this documentary with survivors and people were really raw in their grief and mourning. Because I’m a comedian, I need to be able to laugh at times, it’s like breathing for me, so I asked someone I was working with, “Are there any live comedy shows in town?” And they said, “Yeah, you should go down to this bar to see Jaya’s show.” And for folks who don’t know, Filipino comedy is a bit of a different thing. It’s not quite stand-up like we see in Canada and the US. There are elements of stand-up, but then it also includes singing and dancing and karaoke. So Jaya’s hosting this show, telling jokes and dancing. And then about every 15 minutes, she’ll bring someone out of the audience to sing a karaoke song and as soon as the first person came on stage, you realize that this person is singing the favorite song of a loved one that they lost in the storm, so they start passionately singing this song and they start crying as they’re doing it.

The whole audience starts crying, and this show lasted almost three hours, and after that cathartic moment, Jaya would always come back out on stage and start telling jokes and getting people laughing again. It was really just unlike any live comedy show I had ever seen. You could really see people healing in that space, so I told Jaya right then, “I really want to work with you, especially as a comedian.” I really was fascinated with what they were doing. That was in 2014 and it’s taken us this long to get this movie out there, but Jaya was really the inspiration and their incredible capabilities as a performer.

In that same short film in 2014, I was documenting some of the devastation, which at that point was still much worse because it had been less than a year since the typhoon. There was one shoreside community where some of these ocean tankers were actually thrown onto the land by the storm and they just rolled over homes. I was filming in this area where the boat was still there a year later and there was this boy who was following me around. He seemed really interested in the camera, so I asked him, “Do you want to be on camera?” This was Arnell, who was 13 at the time and I did an interview with him. Then he had me come into his home and I met his whole family. They’re in my first feature film, which came out in 2020, called “When the Storm Fades,” And we’re very proud of the fact that with the theatrical release for that, we were able to raise the funds for his family to buy a new home that they relocated to that was a safe distance from future storms.

“Asog” is my third film working with Arnell in 12 years – I’ve been working with him since he was 13 and now he’s 24, and Arnell’s mother, who was in [“When the Storm Fades”] passed away after the film was finished and not long after that, I lost my own mother – our mothers actually met briefly at one point in the Philippines, so I just really felt for what Arnell was going through. He understood what I was going through and he’s just such a natural performer and had such an incredible story to tell.

So I made this first feature with Arnel and his family and then one day, I looked on Arnel’s Facebook and Instagram and he had done a photo shoot of himself in drag. I had never seen Arnell present this way, but I was so excited and just fascinated that this was this part of himself that he was sharing, seemingly, for the first time. And when I saw him doing that, it started to make me think of Jaya and that maybe there’s a way that they’re connected in a story. [“Asog”] really grew out of that. It started with the three of us, just in a very honest way, talking about the experience of losing our mothers and how we got through that and found joy and laughter despite that tragedy and that really informs the theme of the whole film, which is as much a comedy as it is a drama, despite all of the heavy subject matter.

How did the Filipino folk tale enter the story? It seems like that helped with the structure?

Yeah, that was quite special and quite personal. We started shooting this film in 2019, and like a lot of productions, we had to face challenges with COVID. The Philippines actually closed its borders for almost two years. So we filmed this incrementally over the course of more than four years and during that time, I was putting together edits. There was a point at which I realized the film would benefit from another layer narratively to weave some of its themes together, so that [folk tale] is actually the only ancestral story that I inherited from my mom. That’s an old precolonial story from her ancestors in Bohol Island – I have a children’s book with it, and when I realized the ways in which that story that my mom had given me connected to the themes of the film, it just felt so appropriate to weave that in there because Jaya, Arnel, and myself really made this film [in part] to honor our mothers.

Yeah, our cinematographer Anna McDonald is incredible. She’s a Canadian who worked on my first feature as well, so Arnel had already known her for years. And in terms of working with untrained actors, a big part of it is just trust and comfort. We were truly a guerrilla production, often just two to five people on set, shooting on a DSLR, so we were really trying to make the production side of things less intimidating so [our cast] can forget that there’s this movie happening.

To Anna’s credit, part of what I explained at the start was Hollywood has such a specific way they often film, not just the Philippines, but a lot of foreign countries. If there’s a scene set in the Philippines, you’ll usually see them put that sepia filter on there and it becomes like shaky camera work to express how gritty and dangerous and impoverished this area is. Some of that is definitely a colonial or a white gaze that’s projected onto the way the Philippines is depicted, but when you’re working with folks who live in these communities, the surroundings can look devastating because of these climate disasters, but people still have very real pride and we wanted the film to be from their perspective aesthetically, so we didn’t want to make it gritty or to emphasize the destruction. We wanted to shoot these scenes with a certain cinematic dignity and do our best to capture the real beauty that exists throughout the country. We shot in a lot of these long takes because the scenes weren’t really heavily scripted. We certainly knew the purpose of a scene and had an outline, but the dialogue itself was often just improvised because, again, these people are untrained actors, so most of them not experienced with memorization and they’re really just speaking from the heart. Shooting it in a documentary style allows for the space for unexpected things to happen within a scene and to keep it all in there.

Especially over four years where it might have been an intermittent shoot, was there anything that changed your ideas of what this was or took it in a direction that you didn’t expect?

As you can imagine, this was a micro budget film and we can laugh about the challenging things that happened now because time has passed. But most of the folks in the film are playing themselves and we knew we wanted to have a character in the film who was Jaya’s boyfriend, so I spoke to Jaya and said, “Okay, who should we cast to play this character?” And Jaya said, “Let’s just cast my real boyfriend.” And I said, “Okay, great.” So we shot pretty much all of those scenes and then the pandemic happened and as things go in tales of the heart, Jaya and their boyfriend broke up, so when we came back post-pandemic to finish the film, there were some scenes we needed to pick up with the boyfriend character, but we couldn’t do that because they weren’t together anymore, so we actually had to reshoot all of those scenes.

That time around, I did exercise a bit of producer caution and I suggested, “This time, maybe we shouldn’t do it with your real boyfriend.” So we cast Ricky Gacho Jr., someone who had never been on camera, and the way that Ricky blossomed over the course of filming with us was really beautiful to witness. The film is so much about grief and finding joy after loss and I won’t go into the details of Ricky’s loss, but he was grieving and he was interested in working on the film as a way to process that and move through it. We really got to witness that happening to the extent that we just started adding more scenes for him because we loved him so much. And we’ve seen audiences really appreciate his performance. That was a very special way in which the film grew.

We’re so grateful for our executive producers. They all signed on after seeing the film and each of them – Adam McKay, Alan Cumming, and Joel Kim Booster – were just so excited about the film and wanted to be involved in order to help bring more attention to it and we’re really honored by their contributions. It’s played at over 40 festivals and it actually started at Cannes, where we were selected in a work-in-progress program they have and then we were at Tribeca a month later, and part of what I’ve enjoyed is just seeing the different ways that people categorize and react to the film. The laughter is contagious, especially if there’s a lot of Filipino folks in the room since some of the humor is specifically Filipino.

But we’ve seen it play well in 19 countries now and in Vancouver, for instance, it was categorized as a documentary and at the London Film Festival, I was really honored they classified it as a comedy, not a documentary as a stand-up comedian who’s a huge fan of British comedy. Then we went straight from London to the Warsaw International Film Festival, where it was in the main competition and those audiences were some of the most passionate I encountered. At first, I was confused by it, because my first film, which was a lot about these similar themes, had also done well in Poland and I never understood why. But then when I was there after the first screening, I spent the day walking around in Warsaw, and realized how much this city and this country had been through during the Second World War. You could still see the devastation in the buildings around Warsaw. And then it clicked for me, “That’s why they’ve loved these films I’m making about recovery and resilience and finding joy and hope after a disaster, because these folks know this in a very different way.” In a specific way, they felt seen by the film, which is maybe odd to say, but that was the connection between Poland and the Philippines.

The film also won Best Feature Film at the Hawaii International Film Festival, at the Bali International Film Festival, and at the Ibiza International Film Festival just a few weeks ago, so what we’ve seen there is these different tropical islands and tourist destinations, for whom the last act of the film about the way the typhoon and the land grab related to the tourism industry [connects], they love the film for different reasons that relates to them. So it’s just been incredible to experience the film with different audiences in so many different countries and the fact that their attention and participation in supporting the film has helped pressure the corporations responsible for the land grab to do right by this community has made it all the more special.

“Asog” is available on April 11th on VOD and digital.