When Sarah Friedland was growing up in California, she was obliged to take part in Astro Camp, a rite of passage for kids in the area intended to introduce them to the wonders of the universe, though at eight she was concerned more with her personal space than with the stars up above.

“I remember being asked to do the human knot with a bunch of my classmates, and there were bullies of mine in that cohort doing the exercise,” Friedland recalled recently. “And I was thinking, ‘There’s no way that us moving together is going to make me feel some social cohesion.’ But watching it, I was like, wow, it’s really beautiful — that tension between not having a lot of faith in this choreography to produce utopian or productive social relationships, but at the same time as a dancer and as a visual artist, finding in creative spaces, that moving together can really produce beautiful affects and feelings between a group of people.”

Friedland was originally going to recreate the experience for her latest film “Trust Exercises” before thinking it would be better to limit herself to professional practices that have incorporated movement into building consensus among employees. The director traces three such situations in the 25-minute short — a company retreat where physical alignment is expected to have people putting their best foot forward at a startup, an interview where the push and pull of the conversation becomes an extension of what end needs from one another and a dance company that may expect to move together in unison already but each step is still shown to carry significant risk — and while she may not have included the scene from her youth that inspired her in the first place, she has conjured up the same mix of emotions she felt that day in allowing an audience to bear witness.

“Trust Exercises” is actually the third of an informal trilogy Friedland has put together that consider how people navigate their environments, as much socially as physically, and after making the first installment “Home Exercises” in 2017, in which she channeled her time as a caregiver for artists with dementia into a moving portrait of how the elderly reconfigure their routines to account for aging, her work seems particularly prescient in a world that has been reshuffled and rearranged so thoroughly by a global pandemic. It was downright eerie when the second “Drills” premiered at the New York Film Festival in 2020 — virtually when public gatherings were still a safety risk, and the short itself, filmed pre-COVID, looked at disaster preparedness training and captured the anxiety that can grow out of anticipating the worst. Still, after studying modern dance in college, Friedland has an eye for capturing grace in quotidian activities, with each of her films ultimately evolving into celebrations of kinetic connectivity and the ability to push past muscle memory into uncharted territory.

Shortly before Friedland can finally present one of her films in person at the New York Film Fest where “Trust Exercises” will be making its world premiere as part of Currents Program 9: New York Shorts, she spoke about the impetus for the new work and how it fits into the grand scheme of what she’s been assembling all along, as well as the collaborations that have fueled the three films and drawing on past representations of movement to see where the world is heading.

I didn’t know it was going to be a trilogy when I started making “Home Exercises,” which was the first, but there end up being these threads that I’m still chewing on when I finish the last film, and then that thread gets picked up in the next one. “Trust Exercises” takes up certain things that “Drills” briefly touched on, such as the role of exercises within corporate spaces, and the way in which choreography gets enfolded into different forms of capitalist management. There are intentionally echoes between them, but each film has been made to both stand alone and also speak to the others in the trilogy. Throughout all three, I was thinking a lot about the way in which certain social dynamics or relationships can be staged or rehearsed, but also thinking about the role of choreography and its politics. Since all of them deal with exercises in different ways, I wanted to really explicitly look at the choreographic work of the exercise in this one: what does it do and what does it make possible?

What kind of research goes into a project this?

Across the trilogy, one of the important research practices I’ve developed has been thinking about the interview as an embodied practice and using or transforming the traditional documentary interview into a means of dance making. That has shown up differently in each of the three [films]. In the case of “Trust Exercises,” it took on a completely different form than the research of the other two, and at the same time maintained it — there’s this scene of a session between a body worker and a professional dancer that weaves in and out of the film and I was trying to imagine the form of the interview through their physical encounter. At the same time, we hear them interviewing each other as a fragmented voiceover throughout the film.

Then in terms of the research beforehand, I interviewed a lot of people both in my life and also professionals in the field about trust exercises. That included corporate consultants, people who work in business schools, and a lot of peers who have experienced the choreography or the movement of trust exercises in different spaces. The way that I conduct these interviews is really centered on their experience of embodiment, so I ask people to recall what movement they remember and how did it feel and what did it do? If it didn’t succeed in producing some relationship or feeling that the exercise was purported to do, what lingering feelings did it create for them?

I started working on this during lockdown, so it was less physical than how I normally work with the interview process. Usually, I do interviews within a dance studio or a space where someone can describe a movement or gesture, and I’ll ask them to actually physicalize it for me, and then I’ll perform it back to them. There’ll be this passing back and forth, but because that couldn’t be fully fleshed out in this Zoom interview process, it was really important for me to stage that in a dance studio space and to invite professional dancers to be my co-researchers and to turn that process, which for me in other films has really been off camera, into the scene itself.

I was really fortunate to work with an incredible, incredible group of professional dancers and we did this workshop process together, taking stock exercises that are used within a lot of different work settings for different types of retreats and icebreakers — these hollow exercises of productivity — and turn them into something more intimate and vulnerable, and then to see what other kind of choreographies we could create from those vocabularies.

You’ve got a cross-section of exercises in “Trust Exercises.” Were there certain ones that came to the fore that you wanted to include or did they developed over time in tandem with one another?

They developed over time in tandem with one another. The kernel came from this experience as a student [I had at Astro Camp] and it quickly emerged that I wanted to have some conversation between movement in corporate spaces and the work of dancers. I wanted to interweave them but in a way that I didn’t want to romanticize the work of dancers in a dance studio, because dance spaces can have all of the same problematic dynamics of any other workspace depending on the labor conditions and how the room is being led. So that’s part of why I chose to frame the fictional corporate retreat in a more theatrical space.

Then the body work session emerged as something that was going to happen in “Drills” and didn’t. Paula Macali, the body worker in that scene has also worked as a death doula, and for “Drills,” we had talked the possibility of thinking about preparation for death as another type of drill and looking at the movement of that. It didn’t really work for a number of reasons, but we’ve had this ongoing conversation about her work and its relationship to choreography and its politics, so that developed over time.

I don’t how to account for it because I think my editing process has become somewhat intuitive, and I go into each film with very clear research questions that then become integrated and diffused within the work to the point that I feel questions I answer end up always begetting more questions. Therefore the context of what is opaque and what isn’t emerges naturally in the process and instinctively with my collaborators. Working really closely with performers and with non-performers and having a lot of conversations with them about what they feel comfortable with and what they’re interested in ends up sort of leading us in places where I hadn’t necessarily anticipated, so those conversations in a way end up determining what ends up being present on screen.

In terms of speaking to the editing part of your question, “Trust Exercises” was a little bit different because with “Drills” and “Home Exercises,” I was really specifically referencing the structure of different forms of moving images. In “Home Exercises,” I really wanted to play with the structure of the home workout video, which guided my editing a lot, and “Drills,” I was looking at the social guidance film. Structurally, with “Trust Exercises,” I had a lot of different formal references, namely corporate instructional and ASMR videos, and I was also thinking about the temporality of a dance rehearsal. The braided structure ended up being much more intuitive than the other two, which were very clearly plotted in their form and structure before I started filming.

Because of the fixed perspective of the camera, you do you go in with a pretty set idea of how you’ll shoot the scene before you get to it or is it based on what you see on the day?

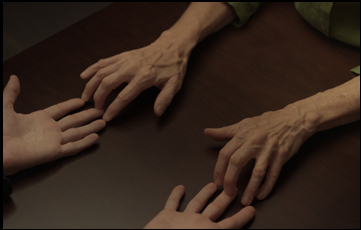

I work with Gabe Elder, an incredible [director of photography] who also co-produces my work, and I’m someone who really overprepares in order to be able to respond very intuitively and spontaneously and improvisationally with my peers in the moment. [Gabe] and I talk for hours and storyboard and shot list very extensively so that we can feel a little bit more available and responsive on set. In the case of this film, I came into it with a lot of very specific political critiques and questions, and the process of getting to be in a room with dancers again, moving together, and the intense emotion of doing that again started guiding the process more than my political or intellectual inquiry. The very, very long take of just two hands touching each other [at the end of the film emerged from] some of our collective desire just to be in contact with each other — physically, emotionally, creatively — and ended up being the stronger affect in the room than some of the intellectual questions that were driving us, so that was really interesting to see just how that desire would shape the space that we were in.

You may be the worst person to ask, but when put together, is there something in these three films you may see that wasn’t there when you first started out on them?

It’s really hard for me to account for what it feels like as a viewer because I’m the one editing these and I’ve just seen them too many times. But the part that’s most moving for me when I see them together is the shared language that’s developed between my crew and I. It’s not just my own. This is really the culmination of our collaboration and I’ve worked with Gabe Elder, the DP, Stephanie Cohen, the production designer, and Assaf Gidron, the sound designer on all three and it’s really satisfying to feel this shared language emerge over the six years that we’ve been working together. There are also a lot of performers that I’ve worked with on multiple films. For example, Hayward Leach, who stars in “Drills” is also in “Trust Exercises,” so that’s the most thrilling part for me to watch them together and see these echoes and threads between them. To feel a shared language is the best feeling ever, and I feel very proud of my peers.

“Trust Exercises” will screen at the New York Film Festival as part of Currents Program 9: New York Shorts on October 10th at the Francesca Beale Theater at 3:15 pm and October 12th at 6:30 pm at the Howard Gilman Theater.