Although there may not have been many to see the potential for a gripping action adventure in the diplomatic relations between South Korea and Africa in the early 1990s when the former was seeking entry into the United Nations, it was surely not lost on Ryoo Seung-Wan, a filmmaker who spent the early part of his career sharpening his skills for maximizing visceral thrills for crime thrillers before turning his attention to international affairs in such films as “The Berlin File” and “The Battleship Island.” While there was much at stake in 1991 when both ambassadors from North and South Korea came to meet with their counterparts in Somalia, lobbying for approval for the U.N. that would lift their international standing, the tension in such polite meet-and-greets generally doesn’t translate to the screen beyond pensive glances and uncomfortably drawn out pauses. However, Ryoo could seize on the fact that this summit between the Somali government and delegations from South and North Korea occurred only days removed from mass protests in the streets of Mogadishu that would plant the seeds for an overthrow of the sitting dictatorship led by President Mohamed Siad Barre, with the Koreans literally caught in the crossfire as the country descended into chaos.

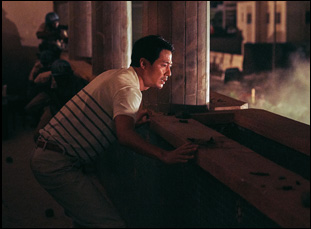

There are surely more than a few dramatic flourishes in “Escape from Mogadishu” as history is refashioned into a rollicking quest for survival for the diplomats, but Ryoo delights in building upon the true details where he can, making the most of out of their mad scramble to catch one of the last flights out of the airport with a rip-roaring car chase and employing a massive set in Morocco when it was forbidden to actually shoot in Mogadishu to recreate a city where the power was shut off and thousands took the streets. Appropriately enough given the cooperation that made a safe evacuation possible, this massive undertaking was pulled off with international collaboration, with the director having to bridge language barriers and coordinate with those with direct knowledge of the Somali embassy and of the terrain in Morocco to bring audiences as close to the reality of the situation as a fictional film could. Not only is there an elegance to how things come together behind the scenes, but on screen Ryoo is able to beautifully weave in how the diplomats from North and South Korea are able to set aside their long-standing acrimony in service of the greater good.

A massive hit in its home country, “Escape from Mogadishu” was selected as South Korea’s official entry to the Academy Awards and recently Ryoo was in Los Angeles to talk about having to create the film’s epic feel from scratch, finding where reality could be more unbelievable than fiction, and knowing when he had done his job accurately.

When I fall in love with something or someone, it’s hard to explain why you fell in love with them. It’s similar when you’re making movies. It’s like I have this almost psychotic moment with the material that I’m about to produce. It’s as if I don’t make this movie I’m going to go crazy and there’s no way of explaining how or why. This incident really came to me like destiny, almost. Several years before I made this film, a younger colleague of mine came to tell me that the company he was working at was developing material that you see in this film. At the time, I wasn’t even thinking I would participate in the project as a director. But as soon as I heard about it, I knew this material was very dramatic and cinematic, so I wanted to see it on the screen. A different director was actually set to direct it, so I just thought it wasn’t meant to be my movie, but two to three years later, this film officially pitched for me to direct and I really started to delve into the research of this incident. When I first received the script, it’s really different from what you see in the finished film you see today and I told the studio that if they gave me the creative freedom to change the script and also to do my own director’s cut, then I would be able to take on the project.

The idea that North Korean and South Korean ambassadors were forced together by this situation and engage is one of the really compelling ones in the film. Was that foundational?

If this was a purely original narrative, I think it would’ve been too unbelievable, but this is a true real-life historical event, and whenever I make movies, I realize reality always moves ahead of fiction. At least once a week, unimaginable things happen. For example, just this moment where we’re interviewing for the Oscar race is surprising for me. [laughs] So the question for North and South Korea collaborating and working together for a certain purpose, that was a very special and unique happening. What actually happened in reality is the North Korean diplomats had met the South Korean diplomats at the airport and then the South Korean diplomats had brought them over to the South Korean embassy. For the movie, we had to condense time, but the most important part of this is two diplomats who are divided are working together collectively.

Also the start of the film is in 1990 and in October of that year, Germany was actually reunified, so Korea is now the only divided country in the world during that time and the two diplomats that are from the divided country are now trapped in a country that also is in another civil war and they’re fighting their own people. This is a really great irony behind this. It goes beyond North and South Korean diplomats working collectively. Thirty years later, Korea is still a divided country and Somalia’s political state is still very unstable, so I thought it’d be good to pose the question, has our world really gotten that much better over the past 30 years?

Shooting a movie that was set in Somalia was basically like filming a movie based in outer space [where we’d have to recreate everything from scratch]. The reason behind that is that Somalia is a country that has travel restrictions, so we weren’t able to go there at all. And it’s not even modern-day Somalia, it’s Somalia 30 years ago, so it was really hard to find material and resources we could reference. Our team worked really hard to find a location that could resemble Somalia the best and we found out that “Black Hawk Down,” which is also set in the backdrop of the Somalian Civil War shot in Morocco, so we went to Morocco. But the location that we saw in “Black Hawk Down,” it wasn’t there! [laughs] The production designer was saying, “This is the spot where the helicopter crashes,” but because there was so much set design and set dressing involved, it was hard for me to realize that.

After a while, we found a small city in Morocco called Essaouira that was really similar to the references we had found, and there was once a time when someone that worked in the Somalian government actually came to our set and they told our producer that if you’re looking for a place to recreate Mogadishu, you found the most perfect place here. When we first started, it felt like we didn’t know what we were doing, we were at a roadblock, and it was really difficult, but we worked until the point where someone familiar with the place themselves said, “This was so similar.” The joy and the energy that we get from making it happen, that was what makes us as filmmakers work so hard.

These felt like some of the largest scenes you’ve presided over – could you feel like David Lean with all those extras?

It’s an honor for you to be mentioning his films in comparison to mine. It was really important for me to show the space of Mogadishu to audiences and [how] the characters were living within this space, so if you look really closely, even in the huge crowd scenes, you can see people very far away are being directed as well. One request that I made for our entire team was not just emphasize spectacle, but rather focus on characters and their situations and making sure they were detailed enough. It’s hard to portray and balance the two, but I wanted to make sure the audience was impacted both by the backdrop and the characters at the same time.

Whenever we were shooting the night scenes, I would ask my cinematographer to minimize the amount of artificial light we used, so our cinematographer did several camera tests – more than normal and he chose the camera that would allow for the most light on screen with the least exposure. After the civil war, the electricity was cut off from the city, so because of that, we wanted to make sure the light of the scene was set by lanterns or other real light. One difficult scene was when we had to shoot the interior scenes at night, we had to light by candles, so we set our exposure extremely low for our camera, but even so, it was extremely dark, so we had to light up a lot of candles. For the feast scene in particular, there’s a lot of actors too and the interior set for the house, there would be a lack of oxygen due to it. [laughs] As we filmed, we talked to each other about “Oh, that’s why in the olden days turned off their candles and went to sleep early because of that.”

The car chase looked incredibly difficult to pull off as well, but there’s a great deal of invention there as well. The notion of how the cars could be protected with sandbags piled on top seems like it’s so crazy it’s true. How did that detail come about?

Originally in the real event, they actually didn’t get the chance to prepare or barricade their car in any way and had to leave, but it is true they were attacked by both the Somali soldiers and also the rebel forces until they reached the Italian embassy. Only one person died throughout that entire time [which] I myself couldn’t even believe when I was preparing this film. Because I’m not a documentary filmmaker, I make fictional movies, I felt that the audience wouldn’t believe that, so I thought long and hard about how I could convince the audience. Coincidentally, I saw a video that showed a rifle couldn’t penetrate through a phone book and we also got advice from military experts who said that sandbags couldn’t be penetrated with rifles as well, so in order to survive, the idea I came up with was to have them barricade the cars with books and steel plates and sandbags.

First off, just 90 films have been submitted from all around the world, so I’m not just going to be focused on just enjoying it, but I’m really going to do my best to introduce this film, not only to Academy members, but also to the general public. I’ve never once thought of myself as a representative of my country. I just simply think that my film is the one selected to represent South Korea and my only wish is that the audience that see this film is that it leaves a lasting and special impression upon their hearts. And it’s hard for me to say I’m either happy or sad. I can’t express my emotional state because it’s such a huge honor.

“Escape from Mogadishu” is now available on Amazon, Google Play, and iTunes.