It isn’t only the fact that their patriarch has died in “A Banquet” that threatens to tear a family apart, but the way in which grief affects Holly (Sienna Guillory) and her daughters Betsey (Jessica Alexander) and Isabelle (Ruby Stokes) in different ways. While the latter retreats into her room as the youngest in the clan with the least memory of what she’s lost, Holly throws herself into the ditch, chopping up vegetables and working out the right mix of spices to show her love and take her mind off of what’s missing as Betsey can’t bring herself to eat, a untenable situation that ultimately comes to a head over a single pea one night at dinner. However, Betsey’s lack of appetite may not be entirely due to her father’s death in Ruth Paxton’s wicked thriller, following the teen out as she attempts to drown her sorrows at a party and ends up further adrift after an encounter in the woods that may or may not have been a hallucination from the powered alcohol she had been fed.

In “A Banquet,” one can never be entirely sure whether what they’re seeing is a breakdown in communication as a despondent Betsey wanders through the wilderness alone or something suspiciously far more sinister, though the brilliance of what Paxton and writer Justin Bull pull off is that there may not be a difference as the horrors of trauma passed from one generation to the next can be every bit as viciously inhibiting as some supernatural entity is feared to be. With a house that’s easy to get lost inside with its long hallways and darkened corners in addition to the unwelcome arrival of the girls’ grandmother (Lindsay Duncan), who brings with her plenty of baggage from the past, Betsey need not be possessed to feel as if she’s lost agency, a destabilization that extends to everyone else in “A Banquet” as Paxton and crew are constantly taking the familiar and warping it in deeply unsettling ways.

What is clear throughout “A Banquet” is that Paxton is a major talent, handling the film’s tricky tone with aplomb and can lean on sharp performances from Guillory and Alexander to power the drama through the silent civil war that is waged all the way through to an eventual all-out reckoning. After premiering last fall at the Toronto Film Festival, the film is now bound to scare up audiences around the world beginning with its release this week across America and shortly before, the director spoke about making the film during the COVID lockdown, working on a film she didn’t write for the first time and the film’s visual inspirations.

So many things, but the scene that made me want to do it was the pea scene. When I read that, I knew I had to do the film because I thought that was a remarkable dinner scene. But beyond that, it’s a film written by Justin Bull and and it was unusual to find something that felt so familiar that felt like it explored themes that were really, really important to me and similar to my own work. So there were these moments in the script that I really wanted to realize, but also this relationship between Betsey and her mom felt so authentic that I knew my own experience I could deepen that relationship and I was very drawn to doing that, but I do kind of joke and say, “The pea scene was the moment, like I love this.”

This may have already been there in Justin’s work, but one of the extraordinary things about this is how this covers generations over this single moment. Was that difficult to pull off?

It was definitely there from the start. There were always those four women in the script and a lot of Holly’s reaction to what was going on with Betsey was very much through the lens of her own experience with her own mother and how she wanted to mother as a result of how she felt she had been. But what I loved about the treatment of the characters and hopefully what we’ve done on screen is there’s no real judgment of any of them. It just shows how hard it is to be a mom and how hard it is to be a daughter, particularly in the modern world. And I like to think that I brought something to each of those relationships, partly from experience, not from being a mother since I don’t have kids. But Betsey’s journey felt so authentic to me, and particularly what happens to Isabelle, which for me is the actual tragedy of this family’s demise — the impact everything has on Isabelle.

The house was a real gift. The problem we faced because of COVID was we didn’t have a lot of options and I knew that the house needed to have personality. I had just binge watched “Ozark” and I loved the space that the family lived in there and how it was so midcentury American domestic, yet it was this setting for all this very dark, unnerving drama. So I knew I wanted [the house] to offer all sorts of interesting options for setups because the film isn’t that long, but we do spend a massive chunk of time in this house and increasingly in Betsy’s room, so we needed it to be a space that we hoped the audience wouldn’t get bored of.

This was a very unusual build [for a house], and one of the reasons why [this particular location] wasn’t an obvious immediate choice was it didn’t tick all the boxes for the script. For example, there were scenes set in Holly’s bedroom and those had to be sacrificed because there just wasn’t the capacity to do that in this house, but it felt like the right setting for us, so it meant that we could tailor the script appropriately. And apart from the obvious “Parasite”-esque landscape window onto a very exotic garden for London, what really hooked my interest was the space that felt like an amphitheater and connects the living area to the kitchen area. There’s something about it that feels like a theater setting, like a stage, and I knew we could start this film in such a way where we watch the tragic death of the father as if watching a play and really set up the vibe that this family’s drama is going to unfold in this space. The house also is unusual in that it has a number of entrances and exits, so we could really play with the psychology of tripping people up, an audience not knowing necessarily who’s coming and going from where.

Dave, my cinematographer, and I, [also] really enjoyed invading personal space, so getting really close up [to the characters] and having these extreme closeup shots compared with leaving a lot of negative space was something we had to be careful of in the house. There was a good variation because you don’t want it to feel sitcommy. You don’t want it to feel soap-like where you’re limited in what you can do and it’s not a build, so you can’t shift walls around. We had to find inventive ways to do that, but ultimately, we just respond very organically to what the actors do in the space, and we always had a plan – but rarely follow it. [laughs]

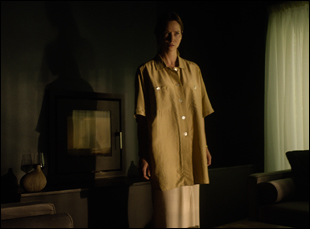

Definitely. This house was white, very white and pristine and modern and very beautiful, but that was not going to work for us because this was a horror film. We needed things to fall off into the shadows, so my cinematographer and I are strongly influenced by paintings — most filmmakers are influenced by Caravaggio, but [also] more contemporary artists like Ken Curry, a Scottish painter who lights the subject rather than the space. We needed to be able to make real dark vignettes in the background, so the painting of the space as a dark tonal color was an absolute must. That was really where the production budget went because it was a very small budget, so we obviously had to paint and reinstate and I wanted it to have a really, really dark green vibe that felt like a dark forestry inside.

What was it like to bring Sienna and Jessica aboard to play this mother and daughter?

I met Sienna just prior to the first lockdown and she was the only actor I met in person before we started shooting. That was a real gift because when I met her, I knew immediately she was Holly, but she was not the Holly that we had written at that point. The script originated as something that was set in a suburb in Boston, Massachusetts and we relocated it to London, so actually meeting Sienna in the early part of that development process really shaped what this family would be like. Sienna’s also a really stylish person, so there was a lot of her own personal aesthetic that we leaked into Holly’s character and her surroundings.

Then Jess was the antithesis for what I thought I wanted for Betsey. She was cast online and that was something I was really anxious about, because there’s nothing that can substitute the alchemy created by people in a room together and the opportunity to watch them move. That’s the thing you really miss is you don’t get that kind of physicality in person, but I had this innocent, virginal, long-haired type “Carrie”-esque figure in mind and Jess is definitely the complete opposite of that and has this incredibly deep voice. She brought Betsey with her — she showed me what Betsy should be and I loved it. The [two of them] absolutely influenced the further versions of the draft as we were going along.

It was. I have a couple of narrative shorts that are more linear narrative dramas, but a lot of the shorts I’ve made explore feelings and moods and don’t necessarily have that character through line, so for this, the real challenge was balancing the experiences of Holly and Betsey, a lot of what’s going on for whom is internal. We worked together to keep it all on track, and I had rough markers in the script for passages of time and where we needed to be and I had spoken to Jess, who plays Betsy, about a gestation period of about nine months — the feeling of a seed being planted and it growing and growing more real to her the longer it grows. But that was one of my anxieties going into it was how am I going to keep track across 20 nonconsecutive days of these characters’ journeys. It’s a collaborative effort because you have to trust your cast to help monitor that too.

One of the ways you get into these internal ideas is the brilliant sound design. Was it fun thinking of ordinary sounds in such a warped way?

For me, the horror is sound, particularly because there are moments where we dip into hyperreal moments in the film. The only moments that [could be construed as] supernatural are not necessarily conscious moments, so everything is rooted in the biological and the reality of being human and we were riffing on sounds of mastication and flesh and of vomit – these were all things that naturally repulsed us as humans that I wanted to infuse in the design. But I love working in sound design and how far it can go. I always want the sound to be bombastic. I want it big and then very, very quiet at times and for me that’s the experience of the horror because what I was trying to illustrate is you don’t really see very much. It’s more about what you don’t see and the anxiety and the dread of what could be.

“A Banquet” opens on February 18th in select theaters, including the IFC Center in New York and the Laemmle Glendale in Los Angeles, and on demand.