There was a unique sensation as a child upon opening up “Cathedral,” the magnificent picture book that David Macaulay put together for young readers that felt very adult in outlining the construction of churches built in medieval times. There was always something you felt you didn’t know from looking at the sophisticated illustrations and the text, but the invitation was there to gradually figure it out, flourishing in the mind upon returning again and again to get to the bottom of things. Within a few minutes into “The Cathedral,” I couldn’t contain my excitement about what writer/director Ricky D’Ambrose was attempting as the same feeling took hold – yes, the Macaulay book ultimately shows up in the hands of Jesse (played by Robert Levey II and William Bednar-Carter at ages 12 and 17, respectively), the central character in his latest film, but after previously scraping together stray items left to discern the whereabouts of someone who has gone missing in his previous feature “Notes on an Appearance,” D’Ambrose chronicles a series of minor awakenings for a child as his parents’ marriage falls apart during the 1990s.

Epic feeling, if intimate in scale, “The Cathedral” surreptitiously pulls in clips of era-appropriate advertising and news to accompany the two decades covered in the lives of the Damroshes and the Alloways, whose fates became intertwined when Richard Damrosch (Brian D’Arcy James) popped the question to Lydia (Monica Barbaro) and had a son, Jesse. Just as reporting about the World Trade Center bombings of 1993 and the impeachment of Bill Clinton over sexual improprieties make it into the head of the young boy without much helpful context, so too does the unhappiness that his parents experience as frustration over bad business decisions on Richard’s part, as well as a hostility towards his father-in-law, mounts, leaving Jesse to make sense of things that are just slightly out of reach at his age. However, emotions are acute when D’Ambrose and crew fashion bone deep imagery of a hyper-specific time and place where one can imagine from the shag carpeting that scrunches up between Jesse’s toes or a look up at a ceiling fan that can stir memories of everything that happened in that space, bringing it back for reinterrogation from an wisened perspective. On the eve of its release on MUBI and in select theaters, D’Ambrose generously shared how he balanced formal daring with personal insight to make the exhilarating family drama, mining the past to make something that so encapsulates to be ever-present.

Interestingly, as a child, I never knew anything about the book. I only knew of a recording made for PBS and it was hosted by David and it was filled with illustrations. I don’t know what prompted my mother to rent this for me on tape when I was a child, but I found it very comforting to watch. The fact that the boy in “The Cathedral – Jesse, who is kind of my proxy, is looking at the book version at a time where he’s discovering something going wrong down the hallway — you see the mother coming out crying — speaks in a way to how the video version of that book entered my childhood, which I always associate with the end of my parents’ marriage in a strange way, so it seemed inevitable that this would show up at such a moment in the film and also give the film its title. That’s not to say that that scene in the film is the pinnacle moment in the film — I don’t think there are any — but it just seemed to make sense that this would provide the name of the movie.

It placed me in this headspace and time period so brilliantly and throughout, it seems like sense memories like a ceiling fan or wallpaper of parrots were actually opening up ideas rather than simply setting a scene. Were there certain things you could build on?

Yes, and this was a strategy with things that were very clear to me in the writing of the film. There would be these images that effectively slow down the narrative, but that are still very important to allowing you to temporarily inhabit the kids’ point of view and even as Jesse grows older, these point of view shots are still there and they refer back to the things we saw earlier in the film. Interestingly, images in the film that the camera stays on that Jesse may not have been in the room for — [for instance] when the glass drops during Claire’s funeral, which is then repeated later on in the film with the smashed glass at the graduation party, we don’t see anyone else in the room other than the woman who’s cleaning up the plates, so it’s almost like the movie starts to take on these little sense impressions [of] the kid’s point of view, these little sense impressions, even when he’s not there. I hope people watching the film aren’t necessarily aligned to the boy, but you’re taking on his perspective without the movie becoming a proper coming-of-age story because it is largely about other things than someone coming-of-age.

Was this tricky to edit? It seems like a lot of the cuts can tell a greater story that what scenes you could’ve included.

Not a very tricky thing to edit, but a tricky thing to write because the film was, while I was writing it, being edited in my head and the fact that I was shooting in places that I was already familiar with, namely my father’s apartment that I knew at the time of writing I’d be shooting in, really impacted in a pretty significant way not only how the film was going to be shot and framed, but how the thing was going to be edited. So the draft of the script that was given to the actors was pretty carefully delineated. If you were to take a look at the shooting script, it is littered with the phrase “Cut to:” The cuts were already in the script and those cuts were determined by pretty extensive outlining process before I started writing. Having those edits in my head but also simultaneously the political/historical stuff running side by side, things that I remembered growing up – the World Trade Center bombing in ’93, TWA flight 800 being recovered from the water, all of that provided its own store of images, and to find ways to interlace those two things was a big challenge.

This seems like in terms of the narrative, you’re letting actors shoulder more of the weight than you’ve been able to before. Was that a different process for you?

It was different insofar as I’ve never worked with casting directors before and with people who had a very good sense of the lay of the land in the theater community in New York and on television who would be able to put faces to the characters and encourage me to consider certain kinds of people. All those people that were presented to me, whether they were tape-recorded or video-recorded auditions or by lists of actors that were given to me to do research on, were all people who came from a very particular acting tradition. “Notes on an Appearance” featured two talented and relatively seasoned screen performers: Keith Poulson and Tallie Medel [but] the actors in my previous films [were] mainly friends and acquaintances who were doing it because they liked and understood what I was trying to do.

Someone like Brian D’Arcy James, who is a storied Broadway performer and Monica Barbaro, who at that point had just come off of “Top Gun 2,” are people who had resources they brought with them that I had to be able to trust and learn to ease off giving them the kinds of directions that I found myself giving to the previous casts, which were very action-oriented, mainly for fear of getting them to try to do something they couldn’t do. So saying “I’m going to let you do what you’ve prepared yourself to do,” and they were very prepared — I was learning about acting in a way I hadn’t before by working with these actors.

I was curious about Candy Dato, who plays the grandmother you get so much from in those scenes of stillness where she’s gazing off silently. What was it like to work with her?

I’m sure she’d be very appreciative to hear that. She’s someone who came to acting much later in life and I don’t remember having very many discussions with Candy or with any of the actors about the characters. Candy was playing a woman — Josephine — who existed and was documented on home video recordings and photographed extensively in my own family snapshot archive and who I think just had to take a look at this woman depicted on recordings and on photographs and she perhaps had an understanding of how to convey whatever she took from those images.

I understand there might’ve been a literal memory bank for everybody on the production to draw on. What was that like to create?

There were risks involved in doing what I ended up doing. [laughs] Which was giving the entire cast and the crew hat were making creative decisions as well about hair and makeup and costuming and production design, access to condensed versions of home movies, beginning with my parents’ wedding video from 1987 – I say condensed because I wanted to find the things that I had were the most salient for these people to focus on. I didn’t want people to sit through a 45-minute recording of something they probably would just be skipping through anyway. The risk is that they begin to do an imitation of the people they see and this movie isn’t fictionalized very much, but nevertheless I didn’t want Brian or Candy or Monica or any of these people to think that they had to just mimic, just do puppet work, as it were, because that would’ve been a reduction of their talents, especially the actors with a great deal of experience and the people who come with a history of performance behind them.

Given the shooting style, it seems like you could redesign this heavily through sound and changing dialogue if you were so inspired by the imagery. Did you find yourself doing that much?

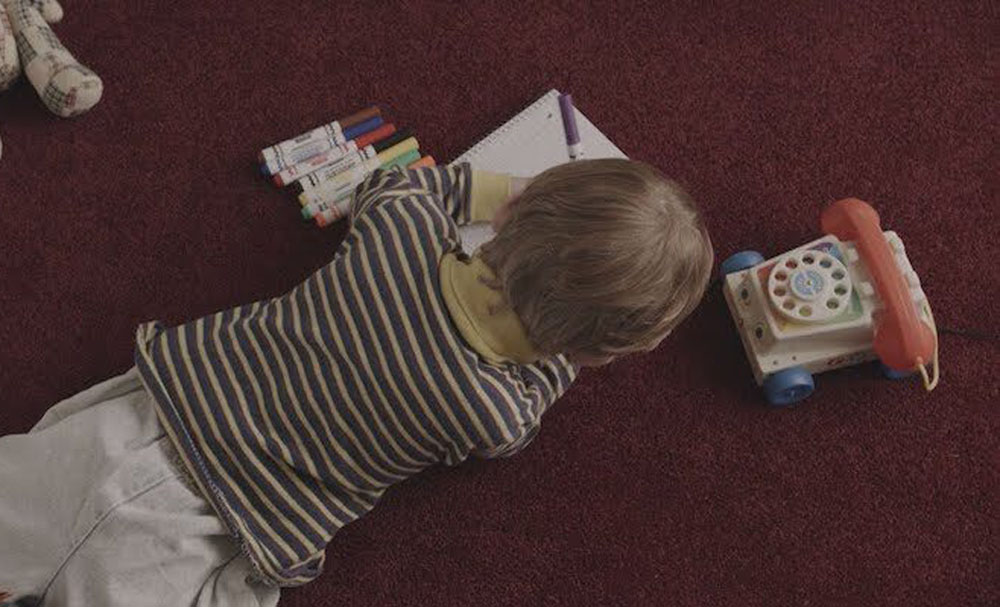

Not so much surprisingly and I think that again goes back to being very prepared during the writing. I mentioned earlier that if you look at the script, you’d see the phrase “Cut to:” throughout it, but you’d also see in capital letters “SOUND:” so the sounds were already paired with the images. There were admittedly things that had to be reworked as a consequence of the limitations of the budget. The shooting script had a number of sequences we couldn’t shoot or we couldn’t shoot in the way I thought we could. Maybe 20 minutes into the film, there was a tabletop shot of Jesse coloring and the narrator is telling us the Damroshes are in the Bahamas and that they ran into the Alloways, and Lydia told Jesse not to tell the Orkins that they saw the Alloways. That’s preceded by a postcard shot of the beach, which leads into this Bahamas sequence. The Bahamas sequence was going to be much more literal and we were going to shoot it in a hotel room. That simply wasn’t possible with the amount of time and money that we had so thinking of how to use sound and images in a way that’s much more contained, and also keeping with the stylistic regime of the rest of the film, so I had to improvise a little bit and tell that in ways that aren’t so explicit.

I just thought it was remarkable and I imagine you consider all your films to be personal, but what’s it like putting something such as this out into the world?

It’s been a really validating experience to have my second feature done what it’s done. I say this as someone who never thought that I would be making a movie about my family, which occurred to me since I was 16, at the age that I am now. I thought that if I were ever to live to the age of 50 and still be making movies, that would be the time in my life where it’s much more reflective. The few times I’ve watched it with an audience, it’s very moving.

It’s strange to see with a group of people who have no relationship to your past, a movie depicting things that only you have access to because you’ve experienced them, and going into my father’s home with people who have no relationship to my upbringing, have never been in that space before, seeing actors dressed as my parents, reenacting things in this space. It isn’t something that I think anyone should ever have to go through — it’s very disorienting, but now having the film gone to Sundance and my God, I’m indebted to the people at the Venice Biennale College because they saw something in here to want to give me a grant to shoot it [because] without them, the film wouldn’t have been made. So to have been in some way vetted this way and to be of interest to people who don’t know me and who may come from completely different backgrounds made me realize by hearing so many people talk about it, I made a movie about many other people’s families, whether they are only children or not, whether they grew up in the suburbs of New York City or not, if by happenstance in a way, I’m very happy about that. It’s taking the public and the private in a very unexpected way and merging them.

“The Cathedral” opens on September 2nd in New York at the Howard Gilman Theater at Film at Lincoln Center, will screen in Los Angeles on September 6th via Acropolis at the 2220 Arts Center at 7:30 pm and streaming on MUBI starting September 9th.