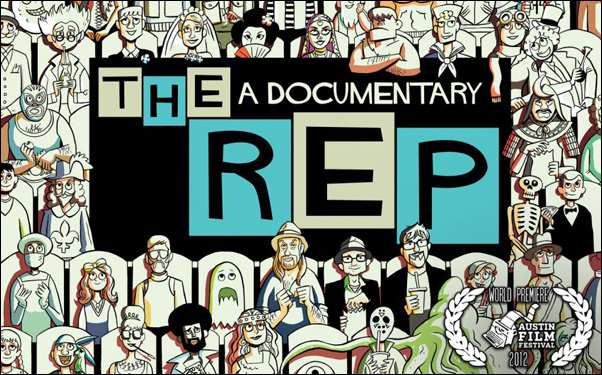

As film fanatics from the world over descend on Toronto this week, audiences who won’t be headed to Canada’s biggest city will be able to catch up with three of its biggest cinephiles with the online debut of “The Rep,” Morgan White’s funny, heartfelt and surprisingly moving documentary about Alex Woodside, Nigel Agnew and Charlie Lewton’s attempt at starting up a repertory theater at a time when most are falling by the wayside.

White ventures beyond the trio’s Toronto Underground Cinema to show the heroic efforts of film programmers such as New Yorker Films’ Dan Talbot, Film Forum’s Bruce Goldstein, the TIFF Lightbox’s Noah Cowan, the Red Vic’s Sam Sharkey, the Austin Film Society’s Lars Nilsen and the New Beverly Cinema’s Michael Torgan as they keep their filmgoing communities alive in the face of audiences that increasingly would rather stay at home and studios that are locking up the 35mm prints that are the currency of such theaters.

Yet in Woodside, Agnew and Lewton, he finds a group of film buffs who are undaunted by such challenges, setting up a sandwich board outside of a nondescript building which houses a 700-seat theater inside in May of 2010, and proceeds to chronicle the theater’s ups and downs during the course of the year, ranging from Charlie going to great lengths to lure Adam West to attend a screening of “Batman: The Movie” to showing the Canadian classic “Cube” on DVD when the print doesn’t show up with one of the film’s writers in attendance and the disc keeps freezing up.

Initially conceived as a Web series, the film places the Toronto Underground Cinema in a greater context, showing the immense cultural loss that’s at stake should audiences continue to move away from the theatrical experience while celebrating the passion of those fighting to save it. (This includes the director, who offered up the film for free to show theatrically after its debut to any exhibitor wanting to show it.) Shortly after the film’s premiere last fall at the Austin Film Festival, White, Woodside, Agnew and Lewton all sat down with me over plates of barbecue to talk about their rollercoaster ride of running their own theater, what it’s like being the stars of their own film and how they tried to convince Atom Egoyan not to do a Q & A after a screening of “The Sweet Hereafter.”

How did you guys actually meet?

Alex Woodside: Myself and Nigel had worked at Bloor Cinema together for numerous years, which is another cinema in Toronto. It’s the biggest single screen cinema in Toronto. It was a rep house for years and years and years; that’s where we met. Then we did a show out of there; do you know what shadow casting is? People get up in front of the screen and they mimic the movie in front of the movie? We did that for “Jurassic Park” for a theatre production in Toronto, and that’s where we met Charlie. Shortly after that, there was some unpleasantness at the Bloor, so me and Nigel left, and … you want to take over there, Chuckles?

Charlie Lewton: After that, we were all looking for work and became really good friends. One night, we were talking about different work and I was saying “Man, I wish I had known you guys earlier so that I could have worked at the cinema with you.” Alex basically said, “There’s this other cinema that the guy who owns it is looking for someone to run.” I thought it’d be too much work, but I contacted Nigel, and the two of us approached the owner and said, “Hey, we’d like to run this.” During that course we brought in Alex in and the three of us started from there.

Nigel Agnew: Charlie and I literally walked in [and told the owner] “Okay, I know how to run a theater, if you pay us, we’ll do it for you.” And he was like “Okay.”

How did you feel when Morgan came in and said, “I want to make a film about you guys”?

AW: At first, Morgan and another guy were trying to start a Web series with another friend of ours, Peter, who’s in the film, at the Bloor. The day they shot the pilot episode, there was an event called the Zombie Walk, and Peter and I had organized a screening at the Bloor that night, but I couldn’t go in because of the general unpleasantness with the owners of the Bloor. We had gotten into an argument over a show I had produced there.

So I couldn’t get [into the theater] and inside Morgan is shooting this Web series about running this event with Peter and another friend of ours named Dave. The whole time, Peter is on the phone with me, and I’m outside trying to figure out what’s going on inside, so that I can run the event from the outside. [laughs] It was crazy. That’s my first exposure to Morgan. We really didn’t even meet that day at all. After our grand opening, Morgan approached us about doing the Web series. I think we all thought it would be fun and a good way, if we could get any traction on it, for people to find out about the theatre.

Morgan White: About a month in, we were all sitting around talking, and I was like, I think I’m going to make this a movie. It wasn’t really a calculated decision, more a realization that I had all of this footage and that the actual story that was going on could never be told in a web series.

I was a little surprised there wasn’t more crossover between the Web series and the film. Was there stuff that you were surprised that wasn’t in the movie?

AW: A little because he was around for a whole year and there was a lot of stuff that happened.

CL: I love how Atom Egoyan made it in there because he randomly showed up one night and he started walking up the steps and Morgan was like “I’m going to interview him!” He grabbed his camera and says, “Charlie, go stall him and I’ll meet you there!” So I run up the stairs, three at a time, [yelling] “Mr. Egoyan, wait, hold on one sec!”

What was he actually there for?

NA: We did a series called “Great Canadian Cinema” and one of the screenings was “The Sweet Hereafter,” so he showed up to talk after the movie, but there were three people in the audience. It was a sad night.

AW: We were trying to get him to commit to coming and he couldn’t because he had something else to do that night, but then he just randomly showed up. We were going to promote it. It would have brought an extra 30 people if we had said Egoyan’s going to be here to do Q & A, but he didn’t [commit] so we couldn’t promote it.

CL: The movie had started and we were like “Oh, thank God, he didn’t come.” (Laughter)

Alex: We’re just sitting around in the lobby waiting for the thing to end and he comes running around the corner like “Did I miss it?”

NA: [We had to tell him], don’t bother, please. You don’t want to go in there! [laughs]

It’s interesting that you had previously worked at the Bloor because the film positions you as three guys who finally get to take control of the their own theater for the first time. What did you bring from past experience and what did you learn?

NA: [The experience from the Bloor] helped us run the place, but I think the actual reality of being at a different location, not having any street signage, made it a lot more difficult. We were sitting there with all this expertise with no one to really use it on.

AW: I’m of the opinion still that when we were running big events, when we got 500-plus people in there, I don’t think anyone in this city could run an event with that many people better than the way we did it. That’s like the number one compliment we always got from our renters. We know our stuff.

Me and Nigel, the last thing we did was for the Toronto Independent Film Festival and during the festival, they had this big banner up from this group that’s promoting all the different film festivals in the city. We went over and looked at it one night and Toronto’s like the capital for film festivals around the world. There were 20 of them up there and we literally went through the list and [we worked] 18 out of the 20 in our tenure as being managers. That kind of experience has allowed us to be able to do actually the day-to-day operations a lot better than anyone else.

NA: Alex and I both started at the snack bar and went from there to management to the booth and just got the run of how a single-screen movie theater works. We really understood it from the inside and out.

AW: But we had never started our own business before. We knew how to deal with all the money coming in and how to account for everything because we had to do that as managers; but having to deal with the owner and his financials and how to balance all these different responsibilities we had to everyone was new to us. It was also atypical because the owner, though, fantastic for having given us the opportunity, never really financed it properly and always kept us in the dark about what was going on with the money.

Because we didn’t have control over that and experience with that element, those two things were really a disaster to be put together. I think we could have been fine if we had control over the finances, but we didn’t so we could never really overcome that issue.

[SPOILERS] The film ends on a troubling but realistic note since the Underground closes and I was a little disturbed to learn during the Q & A you did after the screening that it wasn’t the fault of the staff, which might be the assumption. Was that difficult to portray?

MW: I think the reason why I wanted it like that was because the Underground faces all of the same problems that every other repertory faces. They had the extra thing of the owner having problems, but the point of the film is that we should support repertory cinemas.

AW: At the end of the day, whether or not someone screwed it up, it was our baby, so shouldering the responsibility for what was ours, I have no particular problem with. We tried to make it work and there’s a billion reasons why it didn’t. Even if we had the money, I don’t know if we could’ve made it work. There’s no indication that [space is] a movie theater, especially that there’s 700 seats. That’s a problem that we never were able to overcome and there’s lots of stuff like that. [END SPOILERS]

In our first week we actually got an e-mail from someone who runs a movie company in Canada called Rainbow Cinemas. He was like “Let me start off by saying best of luck, but the auditorium is too small, the screen is too little, the seats are too small for fat people these days … There’s no signage, you won’t be able to project digital stuff.” We’re like “Okay, go fuck yourself! We’re going to make this work.” And we did.

Even in Los Angeles, it’s great challenge. At the New Beverly, they’ve got access to great guests and can be counted on for great programming, but sometimes the audiences are sparse.

MW: When I was there, the night before we did the interview they had flown some director from Europe to do this big screening and they got nine people. Mike [Torgan, the theater’s manager] was like “I don’t know if I should be doing this interview right now because I’m really pissed off over what happened.” I thought, “No, this is the perfect timing to do this interview.” [Laughs] The way that he positioned it was that “Yes, Quentin Tarantino owns this theater [after becoming the landlord when Torgan’s father Sherman, the original owner passed away] and yes, we can survive because we don’t have to pay to rent, but it is a constant struggle.” Tarantino has even said that in interviews before, talking about the New Beverly, “I didn’t realize how fucking hard it was to run a cinema.”

Were other theater operators excited to talk to you?

MW: Everybody except for anyone in Toronto was excited to talk to me. [laughs] When it came to doing the U.S. tour, I contacted Zach Carlson at the Alamo and he suggested all of these theaters. I contacted every single one of them. They were all like “Yes, of course!” So I went to all of those theaters and I think they all thought it was really neat that someone was doing something about this. All these fun, random things that happened, like when I went to Eugene [Oregon] and Ed showed me his collection [of film prints]. I didn’t know that was going to happen; it just kind of happened and it’s so perfect in the film.

It was incredible that you were there for the closing of the Red Vic in San Francisco.

MW: That actually was really hard. They said “no” three times and I kept pestering them and I finally got Sam [Sharkey, the projectionist and member of the Red Vic Collective] on the phone and he was like “Why is everyone saying no? This is ridiculous, yes, please come.” He said “Just show up and I’ll do the interview” and that’s what we did.

They’re going to be so glad, in retrospect that they did that because it was obviously a special evening that should be preserved.

MW: Apparently, they are because Sam posted on my wall yesterday on Facebook saying that it’s a great film. That was great because out of every theater in the film, I was most worried about [the Red Vic] because I really utilized that closing as an essentially dramatic point in the film. Maybe they would see themselves as being poorly represented, but I don’t think that’s the case.

AW: You gave him a lot of time and really showed what was going on there. I didn’t know much about that place before watching the movie for the first time and I got a great sense for what they were doing there and the community that they have there.

MW: I can tell you that being there that last night watching “Harold & Maude” in that theater and realizing this is the last time [they’ll show it] and when it gets to that end when Maude kills herself …

NA: Maude kills herself?! [laughs]

MW: You know, she kills herself on her birthday, and that’s what they did. [The Red Vic] died on their birthday. It’s like you’re sitting there and you’re like “Oh, my God!” Everyone around you, you could hear sniffling and crying. You look back and all the people that were there from the beginning, they’re all standing there bawling their eyes out. You could feel that. I will never be able to watch that movie again. Forever, that’s what “Harold & Maude” will mean to me.

[SPOILERS] That’s what this movie’s about, having that sense memory of when you saw the movie.

NA: When The Underground closed, Alex and I were talking back and forth about what to play. We were going to play something of mine and then I was like “You know what? Fuck it, I’m buying ‘The Last Waltz’” “The Last Waltz” is one of my favorite movies of all time and it’s something that Alex really digs too and we listen to that music all the time.

MW: From now on, for the rest of my life, every time I listen to the Band or watch “The Last Waltz” it will be the last night at The Underground. It’s really bittersweet because it’s really sad but it’s also really amazing that that film connects me to something that is so important in my life. [END SPOILERS]

You get this direct connection to the past, whether it is happy or sad and it will forever mean something to you, greater than the film can ever actually mean. To me, that’s what those rep places are about. You go see this movie that you love and somebody that was in it was there. Like for Charlie, Batman showed up [when Adam West came to a screening]. That has to be one of the coolest things that he’s ever experienced and that’s what you can experience with a rep house. It’s almost like a religious experience. That’s what I wanted to talk about in the film and I really hope that’s what comes across.

AW: It is a heartbreaking thing too, being so aware of what was going on [around us]. Before programming for The Underground, I programmed at University of Toronto for their cinema studies and the student union had a theater. Prints that I had managed to get while I was there two-and-a-half years before starting the Underground I was no longer able to get because they’d already destroyed probably hundreds of prints.

We were doing a series based on the Seven Deadly Sins and we were trying to play “The Edge” with Anthony Hopkins and Alec Baldwin and I couldn’t get it. I’m like “Why can’t I get it?” They’re like “We don’t have a print anymore.” I said, “You had a print two years ago. What happened to that?” They’re like, “Well, it’s gone now.” Talking to people at the Depot in Toronto, I realized that they were just literally throwing away prints.

MW: It’s not even a question of throwing it away, they throw them into a bin and they melt them.

AW: They keep it under tight security too because…

NA: We had an idea to go to the Depot and jump into the bin and see if there were prints in the garbage.

AW: I spent a whole night trying to figure out a way that we could rob it. [laughs]

CL: We were seriously considering doing that though.

AW: Well, why not? They’re just going to throw away everything. When we got that letter from Fox, it was beyond [disturbing]. “The Edge” isn’t a really popular title, so I’m not terribly surprised that they threw it away but they’re going to do that to everything. “Rocky Horror Picture Show,” which plays every month in Toronto and has for 20 years,” will be thrown away in the next year or so. It’s just crazy. Everything out of the studio’s system will all be gone. Private collectors will still have lots of stuff and that’s fantastic, but it’s just so fucking nuts that they’re just getting rid of everything.

To end on a happier note, is it interesting having a film of your own now to look back on? Do you have a favorite moment?

NA: When Sam from the Red Vic is talking about movies and he says “People, we’re all collectively dreaming in a space together,” I think that’s one of the most beautifully-put statements about watching movies I’ve ever heard in my life. Right now, it still gives me goose bumps to even say it.

AW: It’s really weird for us [to name a moment] because when we watch the movie and someone else watches the movie, they’re informed by the movie itself and the sequence of events is what leads them to feel certain things. But for us, every scene and every moment, there’s this whole world of memories attached to it that inform it in this totally different way. It’s a unique experience that we never had before when watching a movie.

NA: Yeah, because some scenes where it looks like we’re having a great time, I remember, oh yeah, that’s the night that right after I left there I got in a huge fight with my girlfriend. Or this is the night where we’re kind of all miserable and we left here and then we went out for beers and it was a good night. It just has this whole different baggage for the three of us.

MW: For me, when Alex says that “This place changed me, but it also changed a lot of people’s lives” [about the Underground], that hits me the most, whenever I think about it is there’s a movie. That changed my life. I’ve always wanted to be a filmmaker and because of this situation, I did, so it changed my life completely. I’m here [at the Austin Film Festival]. I never thought that this would happen.

“The Rep” is now available from iTunes, Amazon Instant Video, YouTube, Xbox 360, Vudu, the PlayStation Network and Best Buy CinemaNow.