Philippe Diaz had been talking to a reporter who covered human rights abuses as he began to pursue “I Am Gitmo,” a drama based on accounts of what it was like to be incarcerated at Guantanamo Bay in the aftermath of 9/11, and she said something stuck with him as he began to think about all that would be involved in bringing a subject to the screen that most instinctively would turn a blind eye towards.

“She said, ‘The last six years made me understand one thing — it’s the limit of the legal fight,’” Diaz recounted as the “advanced interrogation techniques” used against prisoners were gradually recognized as torture. “And it was even amazing that they allowed her to go visit Guantanamo because they knew she would write a report like that, and it was totally damning for the government, but it didn’t change anything. So she [told me] that now we have to bring the fight to another level, which is the emotional level.”

Even if Diaz had never articulated this specifically himself, it’s something he’s long known when his company Cinema Libre Studios has long specialized in distributing films about difficult subject matter, from films charting famine in Darfur (“Darfur Diaries”) to homelessness in Los Angeles (“Lost Angels”) in addition to releasing on some of Oliver Stone’s most controversial nonfiction work. In Hollywood where the company is based, he has run with a different crowd than most film executives in town, connected with journalists and activists from around the world to keep tabs on evolving situations of great sensitivity, and he’d been interested in shining a light on the abuses at Guantanamo for some time, already distributing the doc “Guantanamo Diary Revisited” illustrating the memoir of Mohamedou Houssouahi.

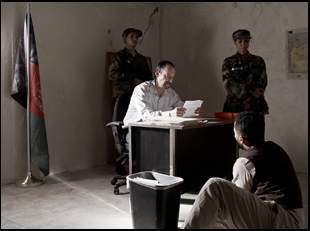

Diaz would argue that despite having to resort to dramatic recreation for “I Am Gitmo,” it is no less adherent to the truth, based on accounts from the notorious detention camp that take shape in the story of Gamel (Sammy Sheik), an amalgam of various prisoners the writer/director had learned of who could be surprised with being hauled in under the suspicion that they had ties with Osama bin Laden and their bewilderment only served to strengthen a case against them that they were uncooperative. The interrogator brought in to question him appears to be just as perplexed when the retired John Anderson (Eric Pierpoint) is flown into Cuba because of his experience, but sees no use for it when those running the detention center operate differently than anyone he ever worked under before and tensions are at an all-time high.

In depicting the brutal conditions the incarcerated endured, the film’s bare-bones production values seem appropriately raw, and Diaz has made a career of doing a lot with a little, both as a director and a distributor simply by shining a light into dark corners that rarely receive any attention. Fittingly, he isn’t only putting one new movie out into the world with the launch of “I Am Gitmo,” but using the occasion to put the entire Cinema Libre catalog on streaming in such a way that will be more equitable to the filmmakers who have entrusted the company with their films and on the eve of a very busy week for the filmmaker, he spoke about his latest film, challenging mainstream narratives both in his own storytelling and as a distributor and adapting to changes in the marketplace.

Before getting to “I Am Gitmo,” I have to start where the film does with this company logo for Cinema Libre, saying “30 years of making a difference.” It must be so difficult to keep going, but is this what you imagined it to be when you started?

Before getting to “I Am Gitmo,” I have to start where the film does with this company logo for Cinema Libre, saying “30 years of making a difference.” It must be so difficult to keep going, but is this what you imagined it to be when you started?

Yes, it started 33 years ago when I created the company here in L.A. and our goal was really to give a voice to the voiceless. Our goal was not to make commercial movies because even during the first part of my career in France, I studied political philosophy and I tried to make a difference in all the feature films I did. I believed very early on that movies can make a difference in the world and these last 33 years proved that true. We have hundreds of e-mails and letters of people saying, “Oh my God, I saw this movie that changed my life. Now I’m doing this and this and that” — and not minor things. So it is very hard, trust me, to produce and distribute human rights-focused movies, but at least when we receive these letters of support, of course it makes us happy.

And this movie [“I Am Gitmo”] opens in New York next week, and for example, we have Karen Greenberg, a law professor who fell in love with the film and is coming to the Q&A with us. She wrote a great book about Guantanamo and she says, “You know, I thought I knew everything about Guantanamo, but when I saw the movie, it was starting anew.” And we have Michel Paradis, a very important law professor as well as lawyers who won major cases about Guantanamo coming in and it makes us feel good because it was very hard to make. We had no time, no money, the usual thing when you make a sociopolitical film, but at the end of the day, we all did that to help the situation.

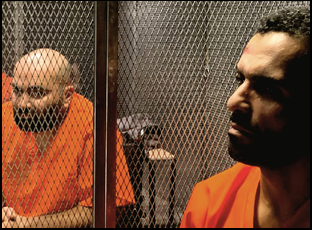

There are 750-plus people who have been sent to Guantanamo, and the vast majority of them were innocent. They have been detained, interrogated, and tortured for the last 10 to 20 years and that’s total insanity. So what we are trying to do with all these important people is not only to say, “Okay, we have to close Guantanamo and we have to free at least the 30 people who are still there today,” because there are still 30 people there for no reason, but we have to call for a definitive ban on torture, which may happen or not. And we also have to call for reparations for these men because they have been stripped of their ID, so they don’t have a proper identification anymore. They are sent to a country which is not theirs, without any money and they are left in the middle of nowhere for them to fend for themselves and they need major psychological help because you cannot be tortured for 10 years and be okay.

I know one man who influenced me a lot to make this movie — Mohamedou Houssouahi, who wrote this book called “Guantanamo Diary.” He was in Guantanamo for 13 years and amazingly, [he remained] absolutely sane and strong, but it’s very unusual. Most of the people I contacted directly or indirectly, they are in such traumatic and psychological shock that they can’t even function anymore. In the movie, I didn’t invent anything, and I didn’t pile up on [a single] character. It was the same systemic use of torture for all of them and it would become worse if they were rebelling for any way. How can the United States be complicit of that? It was something absolutely deliberate and we have to fix the mistake. We have to compensate these men. Their lives are destroyed.

You actually acquired the documentary “Guantanamo Diary Revisited” to distribute at Cinema Libre. Did your desire to direct something of your own predate that or inspired by it?

You actually acquired the documentary “Guantanamo Diary Revisited” to distribute at Cinema Libre. Did your desire to direct something of your own predate that or inspired by it?

No, it’s interesting because I read “Guantanamo Diary” when it was published and I was so impressed by the book because [Mohamedou Houssouahi] related every single day what happened to him in terms of torture, interrogation, and all that. I tried to buy the rights of the book, but it was already sold to this company who did the movie “The Mauritanian.” But after I got in touch with Mohamedou, and I learned that he was making this documentary with a German company and this American journalist, John Goetz, [where he’d] try to find the people who tortured him. It’s a fascinating documentary because he found the main guy in charge of the whole program at the time, the woman who was in charge specifically of directing all the torture over him, and the guy who did the physical torture and he confronted them. I decided to distribute it in the U.S. because it would be great for people to understand.

You actually see the shift in perception happen within “I Am Gitmo” through Jim, a retired interrogator brought into Guantanamo. Did you always have him alongside Gamal as a central character?

Yeah, it was very important for me. But I was very disappointed when I saw “The Mauritanian,” even if it has these great actors and a great director, because Mohamedou’s book is 300 pages long and there are probably 200 pages on the details of torture, but “The Mauritanian,” which is two hours long has two minutes of torture [so you think] it’s not so bad, Guantanamo. The interrogators are super cool. They crack jokes with him. He plays soccer in the courtyard. I’m not saying it didn’t happen, but they rough him up a little bit for two minutes, which is the opposite of what he went through. He went through hell for 13 years. Then at the end of the movie, there is the white hero who saves the day. That always makes me crazy in American movies, because you can talk of any issue in the world, any conflict, any mistake that the U.S. made, as long as there is a white hero who saves the day. In that case, it’s Jodie Foster as his lawyer, and that’s a true story. She fought for him, and she got him released, but the movie is built on that, so it’s more a movie about her than about him.

That’s why there’s no hero in the film and I didn’t want to have the bad people against the good people. That never works. There is one bad character in the movie, which is General Geoffrey Miller, who was in charge of Guantanamo at the time, and he’s the one who devised all these enhanced interrogation methods, as they call it. And after that, he was rewarded and transferred to Abu Ghraib. But even I did not want to make him the really bad guy because it’s explained in the movie that the government propaganda at the time was, you are dealing with the worst of the worst terrorists, so if you believe that, it’s more acceptable to deal with them in harsh way. I don’t think torture is acceptable in any way, in any way, shape, and form, but for the military, that’s a different story. And it’s why I needed the character of Jim, the interrogator,

to put this “normal guy” in front of the reality. At the beginning, he decides to go because he believed that they are the worst of the worst and I have to deal with them and save my country, and be confronted to all this craziness because he was the main interrogator. I wanted to also shake his belief a little bit more too on a personal level by creating a daughter [for him] who is very angry with her father and with what he did in his life. She challenges him all the time.

And Gamal, the main [character] who was tortured, is not an angel. He was part of the war against the Russians, and it’s true that one of the criteria for the military to decide that these guys were bad guys is that they were involved before in the war against the Russians on the side of the Americans, which makes absolutely zero sense. That’s what the lawyer says in the movie. He says he was at the wrong place at the wrong time because he was part of this war 10 years ago on the side of the Americans, and not an al-Qaeda actor who was the partner of the Americans at the time, but now everybody involved in this conflict is suspected of being a terrorist. Any way you take it, it’s absurd, so I didn’t want to make him a good guy, and I didn’t want John Anderson to be a good guy either. They all have their beliefs. One is, of course, deeply ingrained in his Muslim faith, one is deeply ingrained in his Catholic faith, and you see these people who are worlds apart, who have to deal with each other every day and sometimes they look at each other and they don’t even understand, how is that possible that they are so far apart?

And Gamal, the main [character] who was tortured, is not an angel. He was part of the war against the Russians, and it’s true that one of the criteria for the military to decide that these guys were bad guys is that they were involved before in the war against the Russians on the side of the Americans, which makes absolutely zero sense. That’s what the lawyer says in the movie. He says he was at the wrong place at the wrong time because he was part of this war 10 years ago on the side of the Americans, and not an al-Qaeda actor who was the partner of the Americans at the time, but now everybody involved in this conflict is suspected of being a terrorist. Any way you take it, it’s absurd, so I didn’t want to make him a good guy, and I didn’t want John Anderson to be a good guy either. They all have their beliefs. One is, of course, deeply ingrained in his Muslim faith, one is deeply ingrained in his Catholic faith, and you see these people who are worlds apart, who have to deal with each other every day and sometimes they look at each other and they don’t even understand, how is that possible that they are so far apart?

I also wanted to challenge [audiences] emotionally as we are watching the movie, which is why I put as much as I could the camera in the shoes of the guy we tortured. When he’s under the hood, the camera is under the hood, or when he’s put in a box for mock execution, the camera is in the box, et cetera. I wanted people to [ask themselves] what would I think or feel if it was happening to me? What if the police come knocking at my door and say, “Come with us,” and I’m in the hands of crazy people who ask me crazy questions and start to torture me. That’s the whole concept of the movie.

What’s this been like putting this out into the world? I know it’s played a few festivals.

The movie business world changed so much in the last 10 years that we had to change everything too. Now everything is streaming. People go less and less to movie theaters, and they don’t buy DVDs anymore. And that’s fine. We can adapt, but when someone watches a movie on Amazon Prime, we get cents, not dollars for the filmmaker. And not only that, but Amazon can decide to censor our movies whenever they feel like it. The same for Tubi. We decided we are so tired of that because that’s also hurting the lives of the filmmakers [who] put years into making their movie and all the money they had, and Amazon is showing their movie to everybody and sending them pennies. So we decided to create our own streaming and VOD platform that we’ll launch during the premiere of “I Am Gitmo,” called CLS Now TV from Cinema Libre Studio, and we’ll put all these movies [out]. Now the only difference is that there won’t be any censor because we refuse to censor anything and on top of that, the filmmakers will make dollars and not cents anymore.

The festivals pretty much went the same way. I started my career 40 years ago, and at the time, festivals were focused on great movies with interesting subjects, and little by little, it became more and more commercial endeavor. Festivals need sponsors. They need investors. And we had festival censoring our movies because of their sponsors and investors. How is that possible? And for movies like [ours], we don’t have stars, so most of the festivals are not interested. Or I’ve heard “Oh, we love your movie, but you have this religious angle that’s very embarrassing for investors. We can’t do it.”

So it’s very sad, and I don’t know if you followed CinemaCon, this big market event where all the major distributors go to present their movie to [exhibitors], but Greg Laemmle, the head of the Laemmle Theaters here in California, said, “We cannot live on 10 blockbusters a year. During the rest of the year, we need to have diversity and we need to push these movies.” And I agree with that. If we continue this trend of Netflix and Hulu and Amazon going mainstream, and the festivals follow that, I’m not sure what will happen with having people expressing themselves through movies. It’s why we created our own platform because we say we have enough, so let’s hope we can make it work.

That’s exciting to hear, given what a strong catalog of titles you have. And I know “Empire in Africa,” your first film as a director, was something that you were developing around the time you were thinking of Cinema Libre, but did you always see it as a big tent for a bunch of filmmakers and your own directorial instincts grew, or was it the reverse of that where you wanted to direct and saw what a struggle other filmmakers had finding a distributor?

That’s exciting to hear, given what a strong catalog of titles you have. And I know “Empire in Africa,” your first film as a director, was something that you were developing around the time you were thinking of Cinema Libre, but did you always see it as a big tent for a bunch of filmmakers and your own directorial instincts grew, or was it the reverse of that where you wanted to direct and saw what a struggle other filmmakers had finding a distributor?

I had already a production distribution company in France, and it was the time where we had a great minister of culture at the time, Jack Lang, who’s still alive and still in Paris running the Arab World Institute. He did a lot of things for books and dance and theater, but he missed totally what movies are about and he decided that movies had to save the French culture, but what does that mean? It [meant a] French scriptwriter, French directors with French actors in the French language, and I was making international movie at the time, and I was arguing with him. I said, when [a movie] goes to a foreign country, it’s subtitled, so what are we talking about? The French actors are nobody in these other countries. How does that help anything? He was listening to me and said, “Yes, you’re right, Philippe, but it’s politics, so that’s what we’re going to do” and he imposed very strict rules about that. So I said, “Okay, not for me anymore and I moved to the U.S. and I recreated a group pretty much like the group that I had in France [in terms of] production and distribution, and opened the door to all minorities and the social issue films.

Most of my life I’ve been producing feature films, and I started to direct when I felt there was a very important subject, like the documentary I did on the Civil War in Sierra Leone. Of course, who would be crazy to go shoot a documentary in the middle of a Civil War? But I decided to go, and I did the same thing for the other documentary, “The End of Poverty.” But I only started to write and direct when I had an issue and nobody could understand what I wanted to say or didn’t want to do it because there was not enough money or whatever it is, so I decided to do it myself. I don’t see a major difference between writing, directing or producing. It’s all – I have this idea. I want to put it on the screen. How do we do it? It doesn’t matter what I do. If I do it as a producer, writer or director, at the end of the day, we always push the idea we have that we want to put on the screen.

“I Am Gitmo” opens on April 26th in New York at Cinema Village and May 3rd in Los Angeles at the Monica Film Center.