In the early stages of conceiving “A Bread Factory,” Patrick Wang considered playing the role of Jordan, a filmmaker who visits the titular artists’ collective, dismissing questions about what it cost to make the film or what her influences were to implore the small crowd that’s assembled to hear her speak to be bolder. Besides perhaps being a bit too on the nose, the writer/director was intrigued by the possibility of having Janeane Garofalo take on the part because “it becomes something else and you like that thing better and this is one of those literal things where that thing is not you.” Still, there’s no small amount of him in the words she speaks.

“She says, ‘When the muse comes and she gives you a peek, that’s it. You’re done for. You can’t hurt the thing it is,” Wang says of Jordan’s exhortation to young artists to follow their instincts rather than it let take the shape of other things they’ve seen, something that has served him well in his own career creatively. “Not that you know what it is at the very beginning, but [once] it leads you, you can do it no harm. That’s the first task and then everything else, you see how you can help it after it’s done in whatever form it is.”

Wang made these comments in reference to a question he surely gets a lot, and likely tired of long ago, regarding the length of “A Bread Factory,” which is not one film, but two, being shown in tandem starting this weekend in Los Angeles and New York with success determining how much further they will go. Although many filmmakers are hailed as uncompromising, Wang actually is, to the extent that not bending to the whims of the industry has kept his profile far lower than it should be as one of most distinctive and interesting artists working today.

It may have seemed as if Wang snuck into filmmaking from working in the theater to craft the harrowing custody drama “In the Family,” which literally made its debut offshore at the Hawaii Film Festival where programmers were unconcerned by its three-hour-plus running time that likely curtailed its accessibility on the mainland, or when he quietly self-distributed his second film “The Grief of Others” with community screenings in New York not long after its premiere at SXSW. (The film will finally receive a national run on the coattails of “A Bread Factory,” playing at the same theaters a week later.) But by making films without regard for commercial considerations, Wang has crafted some truly exquisite cinematic experiences that have defied the notion that ambition can make art feel intimidating since his work often illuminates our shared humanity, particularly in marshaling cinema’s ability to condense and expand time.

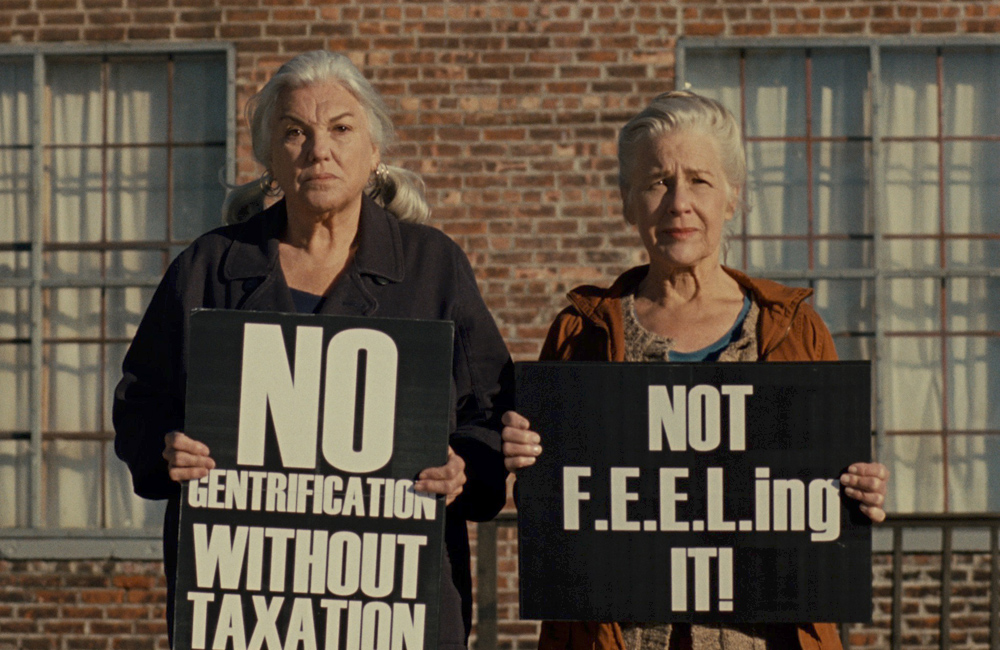

“A Bread Factory” feels as if it may be most personal film to date, even if it’s about his profession as he seeks to quantify what it means to be an artist today. A graduate of MIT, he factors in numerous considerations over the course of the two two-hour films, using “Part 1: For the Sake of Gold” to observe a battle at the regional level over funding for the arts, wherein the city council of Checkford, a small fictional town in upstate New York, is weighing its annual allocation to the community arts center known as The Bread Factory run for 40 years by the same couple (Tyne Daly and Elizabeth Henry) versus endowing a newer arts space, run by a pair of trend-chasing performance artists from China known as May Ray (Janet Hsieh and George Young). In “Part 2: Walk With Me a While,” the budget battle takes a backseat to The Bread Factory’s production of the Greek tragedy “Hecuba,” as the struggle to make great art, watching the actors puzzle over the intentions of Euripides, which makes the Herculean task of financing it look relatively easy by comparison.

One doesn’t need to watch one part of “A Bread Factory” to understand the other, but in divvying them up, Wang inadvertently adds to one of the film’s central notions that art isn’t produced in a vacuum, but its vitality is dependent on the sum of its parts coming together, often in ways that are messy at first. Once the magic happens on stage, it’s evident that all the effort to keep the lights on will be rewarded and then some, yet not only the people involved in the production are required to pull it off, but the community it emerges from including the media that can help spread the word and the audience that will ultimately receive it, and even then, people with competing agendas have to compromise to turn it into something that none of them may have expected and that’s what becomes special about it. The energy that comes from this creative chrysalis makes every frame of “A Bread Factory” crackle as Wang presides over a cast more than a hundred strong, coming to involve tap dancers and musicians as a means of showing all the different pathways the artistic pursuit can take in striving for the same moment of shared catharsis.

While moments like that are unique as it is, “A Bread Factory” is rarer still in being able to articulate what goes into creating them with laser-like precision and good humor, having plenty of fun with characters whose passion for what they do can threaten to overtake common sense, leading to both trouble and transcendence. The healthy mix of both makes for a truly exceptional production and recently, Wang was kind enough to speak about everything that went into it, from the chance encounter he had while on the road with “In the Family” that came to inspire “A Bread Factory” to getting as creative in distributing his work as he is in making it.

The easiest way to talk about that is that we shot the film at a theater [Time and Space Limited] that invited me to speak when they showed my film “In the Family” there. It’s up in Hudson, New York and when I went to go visit, it’s one of those places that you immediately know. It’s a community space [where] you know the kind of love and care it takes to keep it going. It was like a lot of the community theaters I grew up in and learned in and it was a nice thing to think about, but I didn’t think about it as a film. It was just a nice part of my life to remember, but as these things happen, it leads to some other strands of thought. I started thinking about that place a lot. I started thinking about the people that move through there that became less and less what I remembered and more people I imagined and they let me imagine a lot of issues and forces that I wasn’t very aware of when I was younger that are very interesting to think about now.

I’ve seen so many other narratives about the struggle of an artist, but never one that felt as community-based as this is. It’s always treated as a singular pursuit. How did that perspective take shape?

It felt very natural to me, especially as somebody who never thought too much about the arts when I was young. I came to it a lot later than other people, more at the end of high school and in college, and not having grown up with it all your life gives you a different perspective, so it’s not a singular pursuit. [laughs] It gets mixed in with a lot of the rest of your understanding of life and what’s special about those [communal] places is they see art as a way of stepping in and out of your life and interacting with others. That’s not the definition of what art must be, but it is a nice role for art to play in our lives that doesn’t get talked about too much, but can have huge impact in our lives and in our sanity.

Because you have this place Time and Space Limited in mind, what was it like to build a shoot around it as a physical space?

I was worried because by the time we shot the two women who run the place, Linda [Mussman] and Claudia [Bruce] were great friends and film shoots are very invasive. I’ve had one film shoot one scene in my apartment and I don’t know if I’ll ever get over that. [laughs] So I was worried from that standpoint that these are my friends and this is a beautiful space and the crew was mostly outsiders. I was definitely an outsider, so I wanted to be respectful of moving into a small town and the footprint and the wake you leave with your shoot. But all of the great things about shooting in a small town came to pass [with] the people, the resources, the ease where we could make things happen. It was key to making this happen on an almost impossible budget and timeline, and I love that the majority of the cast is local.

Is it interesting to have that mix with folks like Tyne Daly and Janeane Garofalo coming in?

I’ve always liked a range of actors, even from the first film. It was theater actors, TV actors and film actors and actors with decades of experience and actors with very little experience. As long as your actors are generous to each other, you have a very special magic when it’s not business as usual for anybody.

What was important to me is that they weren’t doing impressions of real life characters. There was probably very little danger of that because after the initial inspiration, I took steps into fiction pretty quickly. They have sparks in me at the beginning, but then it’s nice when they step a little outside, so it’s not little versions of you talking to each other for four hours. [laughs] No one is that interesting – well, a few people are, but I’m not. And it goes into many different phases. It can be in the writing where it starts to leave you and it starts to incorporate all these different [elements] and it can happen again in the casting, but [once you cast] the way you also help an actor through that is that you don’t overemphasize any of the particular seeds in reality.

Then as as a writer, you write very specific psychological shapes and moments, but you leave some openness as to what happened before and after. You also leave the space [for the characters] to not define themselves in speeches – to reveal parts of themselves, yes, but not to define themselves. As long as there’s that room, actors bring very interesting things to the table. And actors are all very different and I like how some actors are very detailed — they’re very involved in the costume design, and they can pick out the particular kind of pencil that they hold. We left a lot of space for it and we tried not to overemphasize any of the real world connections.

Since you shoot in long takes, is there much room for spontaneity or is everything locked down in those scenes?

I would break it down along a couple different dimensions – one, we often think of spontaneity verbally and there’s not much room for that. It does come time to time, but maybe a word or two, and if I’ve done my job as a writer, there is enough specificity to the word choice, including breaks and repetitions and pattern to the speaking that it denotes a frame of mind, so you can’t quite change it without changing the frame of mind. Now, there are non-spoken parts and there is space for wildly different interpretations and that’s the space for verbal improvisation, but then the single take actually lets us be a little freer with movement, so actors will often feel a little more spontaneity in movement because we’re lit for broader spaces, so they usually have a lot of latitude to move about the spaces.

You’ve said this might’ve been even more sprawling at some point – what was important for you to keep?

It definitely had many different directions it went at the beginning. At one point, it became a supernatural tale. [laughs] At another, there were a lot more song and dance numbers. Pretty early on in writing, I learned to recognize bad ideas. [laughs] Or ideas that didn’t have a payoff. When you tally up what they give you and what they take away, you were in the debit column, which is pretty much the test for everything. If that calculus led to a much tighter single film, that would’ve been great and much more convenient, but I think you get more with spending a little more time for this world to actually establish and then morph and for characters to really go through a longer timeline of development, especially for some of the younger characters. That’s very satisfying and a hard thing to cram into one movie.

At the beginning, I was thinking it was a miniseries, maybe five parts more in the vein of Bergman’s three miniseries or “World on a Wire.” But I could never get those natural splits into multiple parts, so when I thought about what was happening to this town and then some of the stylistic changes that come later, it very naturally split into two parts. They’re basically exactly two hours each and I knew then that I had the right form. But if you would’ve asked me at the beginning, I would’ve guessed wrong about the form.

Was “Hecuba” always in the mix as the play that’s performed at The Bread Factory?

I was supposed to direct a radio drama production of “Hecuba” and it never panned out, so it was on the brain. But [there were many different] tangential arts at the beginning as just something we were moving through and when I found how those words and those issues in “Hecuba” are the heart of the film, it became much more central – and thank goodness. Otherwise, [there were] all these tangential things, which are nice, but when it comes together and the moment it comes together is very unexpected and it lives up to what we’ve been leading to, it had the weight to be the climax of two films.

There are four credited composers on the film – how did you get that mix?

I think there were four in the first one and [actually] five on the second one and when you get into a community, you want to feel diverse lives and viewpoints, so I thought the music should reflect that. It’s also a little easier to get to work with people you want to work with if you say, “I don’t need you to write music for two movies.” [laughs] It was really nice, the [same] way you get to work with many actors where you get to work with [all] these different composers, fortunately all of whom I knew and I’ve worked with on music before. I was very excited how they delivered for very different musical needs throughout the film. And it was fun [for me] to get to write music for the first time too.

The secret to wanting to do this is to not think about all that. [laughs] But there was a very surreal moment on set where different parts of music that were in different parts of the film were being rehearsed and the groups of singers that never see each other in the film were all together in the green room. And it was very strange because even though they mix in the movie in my head, to have them physically mix in the space — there was a time where two songs I wrote were being rehearsed in two different rooms and I could hear them overlapping, so making movies will get you into these very strange resonances. All these strains of different pieces of my life that I never thought would come together, came together, so it feels like a lot all at once, but when they’re spread out in your life, it’s a different matter.

What was this recent New York premiere like?

It was great and a really nice mix of an audience. There were kids, older people, critics, friends and then just casual passerbys from the neighborhood and it’s always very satisfying that when you make something that’s largely a comedy, to finally be in the room and hear people laughing. I really could not have asked for more.

You’re also bringing out your previous film “The Grief of Others” in tandem with the release of “A Bread Factory,” though I can remember after the festival run, you initially had these special screenings of the film in New York. How have you figured out how to bring these out into the world?

Yeah, it’s been confusing. You’re asking from a point of curiosity, and I think a lot of people ask from a point of wanting some solution. I really don’t have one. When “Grief” was so soon after “In the Family,” I felt I didn’t have the energy to do my own distribution. The film had played so well in France, I thought it has an audience, so it’s not that the movie doesn’t exist and at that point in my life, I tried a more modest solution. It was a solution that got a lot of people to see it, but it didn’t do what I was hoping for ” [which was to make it] a little more sustainable, giving the audience more time to find it. Now something very interesting has come up where I have essentially three movies to show all at once and releasing all three is an interesting question for me in that maybe they can help each other in ways that I couldn’t have if I was just releasing just one. We’ll see soon enough if there’s any weight to that.

It’s something I don’t think about at all. There are many reasons that you can always look at something from the outside and see its [distinctions] and you can point to, “Well, that’s the reason why not.” And I’m not convinced that’s the reason why my films haven’t had institutional support. I think it’s something a little more complex than that because if [the distinguishing qualities such as length] were the case, it would be a struggle. And as I’ve seen it, it’s not a struggle in those settings. They’re very clear about what they feel about the films, but what is beautiful is that at an individual level, largely it’s been critics and journalists, when they see the film, they recognize something unique at play, that unique thing at play that wouldn’t have been there if you were thinking about all these endgames. The film becomes very personal for them and that leaves the film where it needs to be.

“A Bread Factory” opens on October 26th in Los Angeles at the Monica Film Center and in New York at the Village East Cinemas. A full schedule of cities and dates is here.