It was strangely fitting that Patrick Forbes wasn’t initially interested in making what would become “The Phantom,” an unbelievable true crime tale that inspired double takes ever since the tragic day in 1983 when Wanda Lopez, a 26-year-old gas station attendant was stabbed to death in Corpus Christi, Texas while on the job.

“I was making another movie about Wikileaks [“Secrets and Lies”] and I had a brilliant co-producer [Mark Bentley] who said, “Look, there’s this article about this amazing case in the States. You’re got to be interested.” And I said, “Yeah, yeah, don’t bug me. We’ve got enough trouble with Julian Assange,” recalls Forbes. “Then I eventually read the article and it said, ‘Innocent Man Executed’ and I was [thinking], ‘Oh, it’s another miscarriage…’ and then I went ‘Hang on…’ It’s incredibly dramatic inherently and as it transpired, important.”

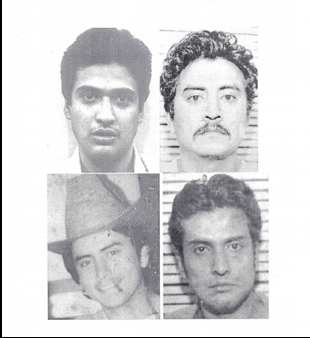

Not long after the crime had been committed, Corpus Christi police apprehended Carlos DeLuna, who was found hiding underneath a car after the violent robbery took place, but as history would bear out, seeking out safety was a natural response to the real killer that had slipped under the radar committing violent acts in the area for years and would continue to after DeLuna, who shared a Hispanic heritage with the criminal and little else, was tried and ultimately given the death penalty for the gruesome murder of Lopez. While DeLuna would never see justice in his lifetime, a class project at Columbia Law 14 years later would resurface the case after seeing the holes evident in the initial investigation and “The Phantom” offers undeniable proof of a legal travesty, heading back to the Nueces County Courthouse and beyond to trace how an innocent man was so easily convicted.

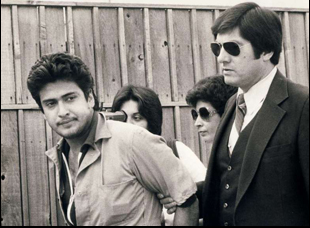

With the case ever-present in the minds of those who were connected to it in some way, whether involved in the investigation or prosecution or part of the media coverage, “The Phantom” feels as if it’s told entirely in the present tense, with subjects revisiting the places in their lives and in their minds that shed light on what happened and just as you sense the experience will never leave them, Forbes makes a film that is bound to stick with audiences as well. Fresh off its premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival where it had been scheduled to bow a year earlier before COVID hit, “The Phantom” is now making its way to select theaters and VOD and the director spoke about how he was able to structure a nail biter out of a case that had been decided long ago, what he was able to uncover on his own in Corpus Christi and in one more twist, how time may finally yield some progress when it comes to criminal justice reform.

I’m going to be as careful as you. [laughs] Have you ever been on a jury? When you’re on a jury, you don’t quite know who to believe initially. You don’t sit there and think immediately, “I know X and Y is guilty or innocent.” You think, “Well, she sounds plausible. Oh, maybe she isn’t. Oh, maybe he’s telling the truth.” The truth doesn’t come at you in an E=MC2 moment. It comes at you slowly, and by surprise often, so I wanted to create a movie about that mirrored life, how you start out thinking one thing and it’s like, “Oh, maybe it’s not true.” It’s as exciting and shocking as real life is, so working it out, it had to mirror the process of finding out the truth and that’s not easy.

Thinking of trials, you actually recreate one in a way I’ve never seen before, having the actual participants relive their experiences for the cameras. What was it like getting people back in the courtroom?

It’s not only the courtroom I wanted to take people back to because so often in documentaries, even really good documentaries, [they] are raging with the lights on. They’re in the room like the one I’m in [now] and the interview’s filmed and they’ve got lights in their eyes and the whole thing feels a bit uncomfortable. And guess what? At minute 90, the poor person is still in the same setting as they are in minute one and actually life isn’t like that. Doing it like that denudes it of significance, so I want to be able to say to somebody, “Where did you see them run?” And they’ll go, “Oh, it was over there.” Or in one terrible case in this movie, “Where was it that you were held captive?” And this poor woman sits there opposite the house where she was held captive for three months and relives the moment that it happened. She went back to being her 16-year-old self and tears started rolling down her face and I’m not a fan normally of showing it, but she just kept going and that was one of the most moving things I’ve ever filmed.

If we’d been doing it in some anonymous room with the usual battery of lights, you’d never have got that moment of truth, and the courtroom – incredibly, the people in Corpus Christi really embraced our movie. The D.A., the chief of police, the court administration [all] said, “Sure, you can have the court where this trial took place,” And everybody started coming back to be filmed and talking about it and one of them said to me, “Look, Steve, who is the prosecutor, he would say this.” And I would go, “Hang on, we’ve got the transcript to the court. Why don’t we get Steve to say exactly what he did say?” Because otherwise I’m having to get somebody to say it and it’s all very cumbersome. So I said to the lawyers, “Would you mind reading out your questions?” Again, if you’ve been on a jury, you’ll know that lawyers aren’t entirely devoid of ego, so they all went “Yeah! Alright.” Everyone started to relive the moment of the trial and get back into it and it was extraordinary to see.

And actually you could see exactly why the person who was initially convicted of this crime was convicted of this crime. The case against him was overwhelming. He lied several times. The prosecuting attorney was completely brilliant. And even filming it, you could sense his power. The defense attorney had only gotten 10 days to get the case together and a $160 bucks to do some research and his client wasn’t telling the truth about everything that went on, so you could see exactly what happened. The prosecuting attorney destroyed the defense and destroys the guy who is accused of the crime and the jury, understandably, thinks he’s just got to be guilty and he is convicted. I can’t go any further because you have to watch the rest of the movie.

You bring this to life aesthetically as well – what was it like figuring out the dynamic camerawork of this? You largely eschew any traditional sit-downs.

I have a brilliant [cinematographer] – Tim Cragg, who actually shot “Three Identical Strangers” a year before and I said to him, “Look, Tim, I want to be in on people’s faces. I want you dancing.” And since I’m the world’s worst dancer, he looks at me like, “Thanks Patrick. That’s going to be great.” [laughs] And I said, “Okay, these are the characters, the people that we’re dealing with – X is big and aggressive, Y is diminutive and adamant” and he completely got it, so I hope the camerawork isn’t just for effect. It’s trying to do that thing that documentary often does, which is get at the sense of somebody’s soul [where] this is the moment that they really overreach themselves or this is the pain that they still feel to this day. That was what [Tim] was so brilliant about. There’s a particularly moving sequence for me of people who the executed man rang or was close to on his last day [before his execution] and suddenly, the movement stops and you’re just on somebody’s face. Tim just moves in and you can see the pain as they all begin to realize firstly that he’s going to die and secondly, perhaps he shouldn’t.

One location that really gave me something I hadn’t considered was tragically the morgue because I haven’t been in many morgues and it was almost like entering a chapel. Again, one of the things that upset and annoyed me about some murder case documentaries is that in some cases, the victim almost becomes irrelevant. It’s all about the guilty man or woman, and it’s like “Hang on, there’s somebody that was killed here.” Going into that morgue and sensing the sadness of the pathologist had looked at [the victim] on the night that she died, you really got to understand the true horror of what had happened and the sadness and loss that permeated out from this quiet, apocryphally green room out throughout the community.

Throughout the whole filmmaking process, you got a sense of the tiny geography of the town. Everything happened about a hundred yards of each other, which makes it all the more incredible that the various things that happened happened because X or Y was living literally a hundred yards from the courtroom, which was 200 yards from where the murder happened, which was a further hundred yards from where somebody had been held captive. It was within a tiny, tiny area of the barrio and when everybody said, “Everybody knew everybody and everybody knew what was going on,” sometimes you think to yourself, “Yeah, sure you did.” But actually when they were just across the street, you could really understand how they’re telling the truth. They did know what was going on. [And you wonder] how on earth didn’t this get introduced in court?

Is there anything that happened while you were making it that changed your ideas of what this could be?

I’m going back to the courtroom because that was the moment I thought, yeah, it completely changed. As I was going around these various places, I suddenly realized in the court that this was effectively and crudely put, the place where largely Anglo-Saxon people in Texas judged largely Hispanic people who came before them and had done so for decades. It’s not the most original, blinding of insights, but you just saw it because all the people on all the benches were all Hispanic and all the people who were trying them were by and large Anglo-Saxon.

There’s a lovely guy who’s in the film who was the victim’s lawyer, and I said to him, “Rene, what did this case mean to you?” And he said, “Look, the reality of this case, the reason they didn’t look so hard…one more dead Mexican.” And it sounds so crude and you’re saying to yourself, it’s so easy to say, but actually sitting in that courtroom, you could see exactly what’s going on because lots and lots of poor people were either enmeshed in a life of crime or judged to be enmeshed in a life of crime and nobody was going to do anything about it or had the money to do anything about it. That laid at the heart of this particular case. Nobody was going to look too hard. It was pure accident that this case was recracked open purely because somebody in a New York classroom said, “Hey, why don’t we have another look at this?” That’s also what my film is about. It’s about the prejudice that’s such a problem in my and your society and the role of accident because I’m a great believer in the cock-up rather than conspiracy theories.

What’s it like getting this out into the world?

Like any documentarian, we’re not doing this to get another Mercedes in the front. [laughs] But once a film gets under your skin, you want to do whatever it takes and however long it takes, so it’s been a bit of a journey — I read that [initial] article in 2012, and the film is only out now, but it’s extraordinary to have it come out now despite the ravages of COVID because a, the world is opening up and B, most importantly, there is a president in the White House who might — touch every piece of wood around — do something about the death penalty off the back of this movie. Having seen the movie, ten major civil liberties groups have launched [a campaign] to try and urge the president to commute the sentences of everybody who is on federal death row, so there might be some good done to society, and the fact that I’m not going to get that Mercedes that you promised me is secondary to the greater good the movie could do now, so it’s tremendously exciting to have it out and it could bizarrely be the right moment.

“The Phantom” opens on July 2nd in theaters, including the Music Box Theatre in Chicago, the Gateway Film Center in Columbus, Ohio, the Sie Film Center in Denver, the ACME Screening Room in Lambertville, New Jersey, the Grand Cinema 4 in Tacoma, Washington, and the Monica Film Center in Los Angeles. It is also available to watch on VOD.