Though they arrived separately, Natalie Kottke Masocco and Erica Sardarian could smell the town of Crossett a mile away. The small town in Arkansas has the distinction of being “the forestry capital of the South,” making it a hotspot for the pulp and paper industry. Yet as Kottke Masocco and Sardarian’s “Company Town” shows in recent years, Crossett has become known for something else entirely, with many of the residents describing the scent of akin to rotten eggs as just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to toxicity they’ve come to call “Crossett Crud” that has poisoned the community.

“Once you get into that town, you can feel the pollution on your skin and on your body,” said Sardarian. “The hydrogen sulfide immediately just hits you in the face, so I personally felt sick. Edgar, our [director of photography] and editor got nosebleeds.”

“This is what [the residents of Crossett] experience 24 hours a day, so for us as filmmakers to be there for a short period of time and leave, we felt so much compassion for what they’re going through,” adds Kottke Masocco. “Our scientist, Anthony Samsel, describes the pollution as World War II mustard gas. That’s how bad it affects these people living in this day in and day out.”

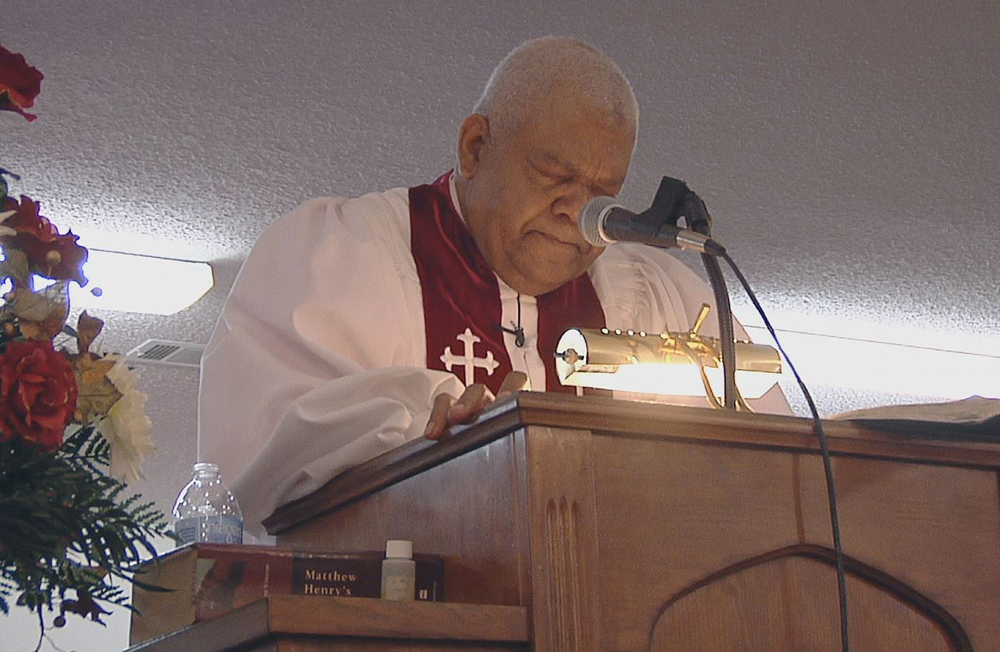

That feeling is made tangible in “Company Town,” a blistering expose which Kottke Masocco and Sardarian dedicated themselves to for the past four years, charting the crusade of Pastor David Bouie as he rallies Crossett to bring deliverance from the sickening pollutants thrust into the community every day by the Koch Industry subsidiary Georgia Pacific. With an estimated 45 million gallons of waste water pumped into the Ouchita River that runs through town on a daily basis, Bouie can no longer use his own hands to count the neighbors on his street that have contracted cancer, with many either working directly or connected to someone working for the company with their right to a healthy life compromised by their need to make a living. The filmmakers watch on as Crossett is systematically disenfranchised, all but ignored by the Environmental Protection Agency and disregarded by Georgia Pacific, which sends people door-to-door to buy residents’ “health rights” for pennies on the dollar.

While Kottke Masocco and Sardarian returned home without the ending they wanted, they are working on changing that starting with the film’s recent premiere at the Los Angeles Film Festival and after a triumphant premiere, the two spoke about how they first learned of Crossett and became a part of the community, conveying such a complex and arcane pollution scheme in dramatic fashion and trying their best to avoid becoming part of their own film.

Natalie Kottke Masocco: About five-and-a-half years ago while I was working on “Koch Brothers Exposed,” a documentary directed by Robert Greenwald of Brave New Films, I met the main subjects, Mr. David Bouie, [his wife] Barbara Bouie, and Cheryl [Slavant] the Riverkeeper, along with other residents, [in] researching Georgia-Pacific’s pollution. I spent a couple years building trust and learning about the really horrible cancer and illness that’s been going on in this town, and knew there was a bigger story here than just this five-minute piece on the Koch Brothers. I’d never directed a feature, but we wanted to make a full film about this community’s decades-long fight for clean air and clean water, something that should be a human right, and what it was like on the inside, so we started laying the groundwork. The residents became very close to me, like my friends and family and Erica and I teamed up to begin this four-year journey of following this story of how this pastor, with the government’s involvement, organized [a campaign] and it just unraveled with all of these stories.

Was this difficult to get your arms around as filmmakers?

Natalie Kottke Masocco: It’s a very complex issue, socially and politically. The jarring thing upon meeting the people is this total disbelief that this is their life – that this is the air they’re breathing and the water they’re drinking and to wrap your mind around living in that day in and day out. That’s what really led to this obsession of getting to the bottom of things, and trying to make something right out of something so wrong. As we’ve learned more about their plight, it became clearer and clearer why this is happening. The pollution is astronomical and the government, just like we’re seeing in Flint, Michigan, isn’t doing anything about it.

Erica Sardarian: It was very tough as filmmakers because we were all so emotionally invested in the people in this story, and [it was difficult to] separate ourselves from being part of the community and and then also being filmmakers. There were times when we were very frustrated with the government and their wrongdoing and seeing how things were unfolding and not understanding the full picture until we were actually there. When the EPA was on the ground and they wouldn’t investigate any further, that’s when it became very obvious to us that there was something wrong here.

Natalie Kottke Masocco: As filmmakers we really wanted to blend this vérité approach with documenting the internal ongoings of how you build a movement in a true company town like this without putting the filmmaker’s voice in the story. That’s why we didn’t use narration. We really wanted to tell the story from Pastor Bouie’s perspective, as he’s representing the citizens of the town, so we would strike that balance of not revealing our voice within the story and, as much as possible, letting their voice resonate.

Natalie Kottke Masocco: We documented this in real time, and when I first met Pastor Bouie, he was the most vocal. He’s a pastor and he’s a deputy sheriff, so he embodies this leadership naturally as who he is, and he’s a really fascinating character. There’s so much fear in the town and when I first went there, not many people would talk, but right away he was talking, and right away he was speaking truth. On his street alone, there’s 11 out of 15 homes that have cancer deaths. He lives right near the pollution, so he was the first to come out and really inspire others to follow his lead, so authentically he was leading this environmental movement there and as this investigation unfolded, [we learned of] Cheryl [Slavant] the Riverkeeper, she’s like the Erin Brockovich of the story. She was hugely impactful in his fight.

You also have a whistleblower who worked at Georgia Pacific who comes forward through the course of your film. How did you meet him?

Natalie Kottke Masocco: It took years to get someone to come forward, but we really wanted to show that inside man’s perspective. We searched and searched and Cheryl Slavant, the Riverkeeper, met a novelist writing a story about the town, and she connected us to the whistleblower.

Erica Sardarian: [The whistleblower] was the one thing that was missing from our film to really hone in on what is happening in this town, and be the voice of reason in terms of showing us we’re not just speculating, so it took a lot of digging. Cheryl [Slavant, the riverkeeper] found this woman who actually came to her and knew someone who worked at the mill. That’s how we started building that relationship.

Natalie Kottke Masocco: We spent a lot of time talking with him before ultimately he went on camera. He risked so much to come forward in this story – he has spent his entire career working in environmental and chemical plants and chemical cleanup and in order for him to actually come out in the film, he had to leave that career and start a whole other career, which was a scary path for him. But he was horrified by what he witnessed – and you see in the film the pollution that’s buried behind the homes on this massive 400-acre piece of land in the woods. He’d never seen chemical disposed of this way in his life, and he had 25 years of experience. It was a tremendous risk for him to show us this wasteland, and we see the workers out there with the excavation, burying it. That’s one of the things in the film that we really are trying to get across is that this is not only is an air and water pollution issue, but we have a former worker who is showing us that this is how a massive company that everyone knows in America – Georgia-Pacific – is disposing their waste. It’s ruining people’s lives. We have this 9-year-old cancer survivor Simone in the film, who lives near that dump site the whistleblower shows us.

Erica Sardarian: Natalie had worked on the film “Koch Brothers Exposed,” so she knew the town, but I had no idea some of these things were happening in this community. The contract to me is the most shocking, and if that’s not an admission of guilt, I don’t know what is. As things started to unfold, like the EPA being on the land and not doing anything, I was just shocked. There were so many moments where we as filmmakers were surprised and angry, but also at the same time we hold ourselves back and not get involved personally. There were so many times in the film where we all felt helpless.

Natalie Kottke Masocco: The other thing about the health contract is that after we learned about it, we were blown away that a company could buy someone’s health and property rights and on Mr. Bouie’s street, a black neighborhood, they offered [contracts] starting at a few hundred dollars to sign back in the ’90s. A few streets over on Thurman Road, a white neighborhood, some of those folks were paid off a couple hundred thousand dollars and relocated because of pollution. None of the people on Penn Road where Mr. Bouie lived have been relocated, and they were offered substantially less money than the white neighborhood a few streets over. That is where this is an environmental justice issue because the predominately African-American people on Penn Road live right near the waste water discharge. A complaint was recently filed by Tulane environmental law clinic based off of this to ask the EPA to investigate this because these people are disproportionately affected by this pollution.

Although Erica mentions the need to hold back personally, at least did you find yourselves serving as a conduit for information between all these various parties figuring out what was going on?

Natalie Kottke Masocco: Yeah, we all collaborated in a way. It was very interesting because we started gathering health surveys five-and-a-half years ago. At first, there were only 30. Now there’s about 600 and those are funneled to the scientists like Anthony Samsel, Cheryl the Riverkeeper and then Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, so there was this information that we were all feeding each other and still are as it was happening. The Tulane Environmental Law Clinic’s work is really amazing on the issue and they’ve all been very collaborative, so everyone’s on the same page to put the most amount of pressure to building the biggest case we can build.

Erica Sardarian: That was the toughest part in terms of our edit. We wanted it to end, like everyone, with a happy ending, and the town is still working towards getting that resolution. It was really hard for us to say, okay, we need to get this film out there, but with what’s happening now in Porter Ranch and Flint, Michigan, had this film been released six months ago or a year ago, it wouldn’t have garnered as much attention. It came to a point where we were all really happy with where were were at with the story and we’re excited to get it out there.

Natalie Kottke Masocco: I felt really proud of how long we stuck with it and really privileged being able to work with the community so deeply and document their struggle. And this is not over. Our real goal is to utilize this film as a vehicle for change in this town and we have very specific paths to put pressure on the EPA with this film — we want this pollution cleaned up, and we want the affected citizens relocated. This is the same situation as what’s happening in Flint, Michigan. Government regulators are looking the other way, and a lot of people are suffering, so we’re hoping that this film will get people angry to help make change.

“Company Town” opens in New York on September 8th.