Matthew Heineman has never thought twice about throwing himself into highly charged or potentially dangerous situations, so it shouldn’t have come as a surprise that the director of “Cartel Land” and “City of Ghosts” had been eager to find a way to the frontlines of the battle against COVID-19 pandemic to see for himself the devastation the disease had wrought on hospitals overwhelmed by an influx of patients with no known treatment to save them. Still, it was hardly their first priority to let his cameras in, much as the access might serve as an important historical record to reflect on after the initial panic had passed, and while Heineman wasn’t one to interfere or question their resistance, he did have the tenacity to ask if the Long Island Jewish Medical Center might open their doors just slightly enough to show what was going on in those first pivotal months of the pandemic.

What Heineman was able to bear witness to in “The First Wave” will surely stand the test of time as he gained access no other filmmaker of his stature did in America, chronicling the chaos of those early days of teams of doctors and nurses intubating patients one after another, unsure of what exactly is causing their respiratory issues and fearing that if not properly protected, they will fall prey to the virus themselves. In fact, “The First Wave” comes to follow Brussels Jabron, a nurse from a family that has long dedicated themselves to caring for others and find themselves at her bedside as she struggles to breathe after just having a baby. Also on a ventilator is Ahmed Ellis, a 35-year-old NYPD officer who can’t communicate with his own seven-month-old son when it takes too much energy to talk. They can at least take some comfort in the steady hands of nurse Kellie Wunsch and Dr. Nathalie Doughe, two members of the formidable staff at the New York hospital who put on a brave face for their patients, but as Heineman reveals are dealing with a considerable mental toll as they see the loss of life in all directions, even if they remain untouched by the virus physically.

Heineman and an intrepid crew were faced with the same issues, unable to take breaks from the film’s subject matter even if they could leave the hospital after long days of filming without any idea of when to stop. Ultimately, the decision to contain “The First Wave” to March to June of 2020 and sticking to a single location opens up the film to the visceral experience that Heineman is particularly gifted at engaging an audience in, at first immersing one inside the massive machinery of the medical center from its equipment to its staff and gradually coming to admire how humanity finds a way to break through. With the film opening in theaters this week following a fall festival run that culminated with a hometown premiere at DOC NYC, Heineman graciously took the time to talk about how he was moved to action when first hearing about COVID-19, navigating such precarious filming circumstances and what his hopes are as far as what consideration it may inspire.

I woke up in March and like everyone, I was just terrified about this tsunami that was about to hit our country. I think we were all inundated with stats and headlines and misinformation and I just felt this enormous obligation to try and humanize and put a human face to this epidemic, so that’s what we sought out to do — to actually pull back the veil on what was happening inside hospitals. We reached out to hospices all across the country and we got rejected for the most part. it was a difficult thing to buy into, but we finally got access to a hospital here in our hometown in New York. I didn’t want to tell the story retrospectively or through Zoom or the various ways that most of these news stories and other documentaries were being told [in the moment]. I wanted to put audience members inside the shoes of doctors, nurses and patients on the front lines, so that was a difficult thing to get buy in on, but that’s what we ultimately got.

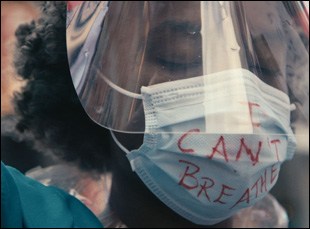

Honestly, one of the greatest tragedies of COVID for me is that it became so politicized. It didn’t have to happen that way. This was an issue that could’ve brought our country together, but instead, it further divided us and I believe that in those early weeks and early months if we had more imagery of what was actually happening inside hospitals, all the conspiracy theories and misinformation that started to be transmitted around the country might not have happened to the degree that it did if we all had these images that we could rally around as a society.

It sounds like you hit the ground running, but in terms of finding which subjects to follow, could you do any prep to, for lack of a better word, “cast” this? From what I understand, patients were initially off-limits, but you clearly get the trust of them and their families.

People don’t like to talk about it, but casting is incredibly important in a documentary. It’s as or more important than in a narrative film, so the participants that we follow are all our storytellers and finding Dr. Douge, and Ahmed and Brussels were essential in telling the story. The basic set-up with Long Island Jewish Medical Center is that we would start filming with doctors and nurses, but we weren’t allowed to film with patients. After a week or so in which we proved we had a very small footprint and we were filming with integrity and honesty and with respect, we started to get the green light to start talking to patients and that’s when we started talking to Brussels and Ahmed. I wanted to find human beings that were going through this crisis. I wanted to see how they change and how this impacted them, and in the case of our patients whether they were going to live or die and how is it impacting their families, so I owe an enormous, enormous amount of gratitude for letting us in at an incredibly difficult time.

It was definitely the hardest film I ever made, physically, emotionally and logistically. The whole thing was a massive effort with the incredible team that I worked with and we knew so little about how the disease was transmitted and the science of it all, so at that point, all the things you take for granted when making a doc were weaponized – putting a lav mic on somebody, putting a camera down on a counter, taking your mask off and trying to eat. Everything had the potential of getting us sick and contracting COVID, so we had to develop safety protocols to the best of our ability. The last thing we wanted to do obviously was to get our crew sick and/or worse transmitting the disease to people we were filming with. But we were extraordinarily careful and I’m really proud to say no one on our crew got sick.

Obviously, so many things you learn in the edit room and obviously, the cliched difference between a narrative and a doc is people say that narratives are made in the script and docs are made in the edit room. I don’t think either of those are really true, to be honest, but of course there’s things you discover when editing a doc and as we cut the film together and interweave storylines, there was a real natural arc over the course of the first wave. Coming up with that title “The First Wave” had real story implications [because] we shot past the first wave, through the summer and the fall and every time we put in those scenes, it just didn’t work. So coming up with the title with “The First Wave” and those goalposts from March to June created a very natural arc for all the subjects that we filmed with. Then the ability to open up the film and find moments of humor and levity were really important to keep people engaged. I hope and I think that the film touches on every aspect of the human condition.

That’s why it seems to be having such a strong effect on people. What has it been like to take this out on the road?

Having been so isolated from everybody, all of us experiencing this in our own ways, separated from each other and coming together and experiencing the film together has been a really beautiful, emotional, cathartic experience. It’s been incredible screening the film at festivals. We had our big premiere last night at the Beacon Theater and it’s been amazing screening the film for people in person — some of the most emotional screenings of my career. And I think there’s no question that we’ve all been changed forever by this. I’ve been changed, our families have been changed and the fabric of society has been changed and the way we communicate has changed, so my hope is that the film creates a space to reflect on all that we’ve been through and what have we learned? And how can we apply that going into the future?

“The First Wave” will open in select theaters on November 19th. A full list of theaters can be found here.