At one point in “Limonov: The Ballad of Eddie,” a potential publisher is trying to help the title character played by Ben Whishaw refine his novel, a clearly personal tale of alienation that might work commercially if it were a bit more like the hit of the moment “Taxi Driver,” actually wishing that he was a little more like Travis Bickle who he felt had at least a couple of redemptive qualities. “The problem is your main character,” he concludes, something that clearly isn’t for Kirill Serebrennikov, who may be more charitable when like Eduard Limonov, his outspokenness has made it all but impossible to remain in his native Russia and has a certain understanding of someone who would abhor being seen as heroic, but interesting and defies easy categorization, making this exhilarating and occasionally exasperating profile of the irascible iconoclast feel like a fair reflection.

When your main subject picks a pen name after the Russian word for hand grenade, you can expect a certain level of combustibility and while “Limonov” may ultimately follow a fairly linear timeline, it has the twitchy energy of feeling as if it’s constantly teetering on the edge of exploding as Limonov tires of working in a factory and christens himself as a poet, though he’d be the first to tell you he hardly has a way with words. What he does have is an endless reserve of anger and the kind of self-confidence in his cynicism that makes one think he knows something they don’t, ushering him into hip high-society circles where he can be counted on not to be boring and surpasses his social standing by charming a model named Elena (Viktoria Miroshnichenko), but not all the attention he receives is wanted when the KGB, looking to gain moles within the artist community that Limonov himself has weaseled himself into, attempts to recruit him and when cooperation is never an option, he and Anna depart for New York.

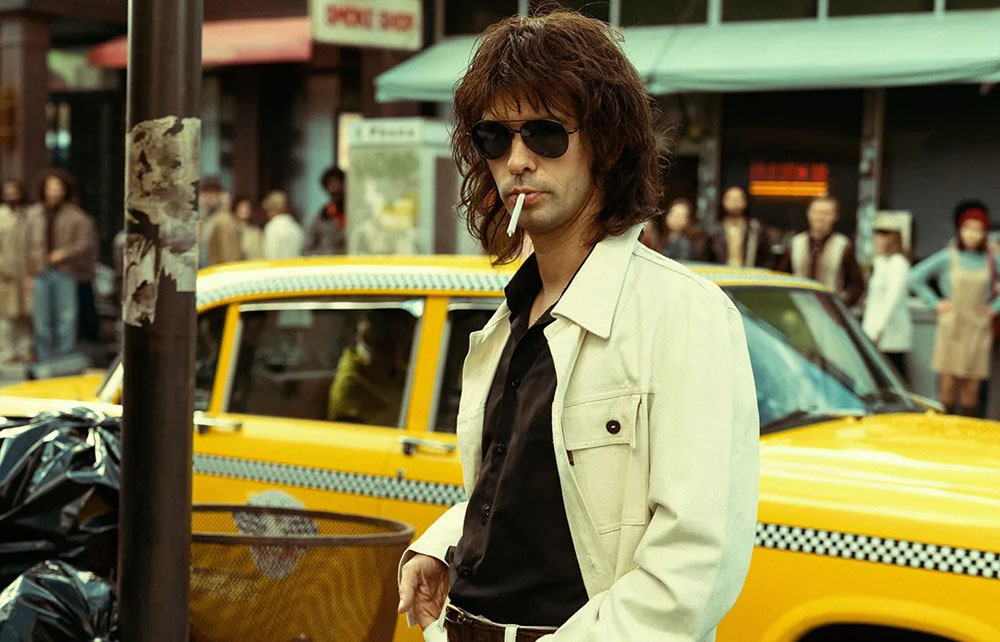

Throughout “Limonov,” the most propulsive scenes are set in the streets outside of the walk-up apartment that Limonov and Anna share near Times Square, a remarkable bit of production design by Lyubov Korolkova and Vladislav Ogay that has one foot in reality and another in the fond retroactive fantasies of the scuzzy charm of the city during its disreputable days in the ‘70s, with Serebrennikov tuning up “Walk on the Wild Side” as if everyone on the street can hear it and dance along. (Even more impressive is a sequence in which the entire Cold War is told via televisions on the street where the general detritus in New York reflects the rubble in Russia.) The director recognizes these moments where Limonov can find a flow are precious and lets them play out in long, invigorating takes where one can feel the freedom he does when he’s allowed outside of his tortured mind. But for better and worse one can feel the labor behind scenes of just getting through his life, unsettled as an ex-pat and at odds with the way society operates on any continent, yet a keen observer of the weaknesses of the system in ways he can reflect to the public and exploit himself, eventually taking a job as a lowly butler that can afford him the time to write and gather juicy material about the bourgeoisie.

Whishaw is magnetic as Limonov, credibly covering nearly 40 years with an aggressive Russian accent that may or may not be authentic but surely feels true to the spirit of the character, and it’s surely a wise decision on the part of co-writers Serebrennikov, Ben Hopkins and Pawel Pawlikowski (who apparently attempted to wrangle Emmanuel Carrère’s biography of the poet into something he could direct himself) to skip any ponderous passages of either writing or reciting his work. Still, in folding his arch tone into the fabric of the film rather than make a plot point of it, mostly resisting the more typical narrative in which how he became a literary sensation in the east, “Limonov” runs the risk of being slightly more brusque than it’d like to be for those unfamiliar when his fame likely excused so much of his bad behavior that isn’t accounted for otherwise on screen. In his first English-language film, Serebrennikov also includes scenes and dialogue that can feel a bit on the nose, pulling one out of the euphoria he’s shown himself capable of conjuring in “Petrov’s Flu,” “Leto” and this film when it’s at its best.

However, “Limonov” would disappoint if it were an entirely easy sit and by the time its main character arrives back in Russia in the ‘90s as a folk hero who ignited a real movement as the founder of the National Bolshevik Party, a mix of radicals from both ends of the political spectrum, his appeal is understood. Rather than tell a life story, it’s a story that comes alive.

“Limonov – The Ballad of Eddie” will screen again at the Cannes Film Festival in Competition on May 20th at 8:30 am at the Grand Theatre Lumiere, 9 am at the Cineum Imax, noon at the Agnes Varda Theatre and 1:45 pm at Licorne, May 21st at 4:15 pm at Cineum Screen X and May 22nd at 9 am at Cineum Aurore.