Ever since Doug Pray first saw W.T. Morgan’s 1986 rockumentary “X: The Unheard Music,” a profile of punk pioneers, he could never forget the indelible and inexplicable sight of the band playing the film’s title song inside a house that’s being moved across Los Angeles on the freeway.

“I’ve always been fascinated by large-size, heavy load kind of things like when they move a house down the street,” says the accomplished documentarian, who notably satisfied that interest previously with the 2007 film “Big Rig.” “[“X: The Unheard Music”] just struck me as that is the ultimate L.A. film because the band and the punk rock movement are just so very, very L.A. in a great way.”

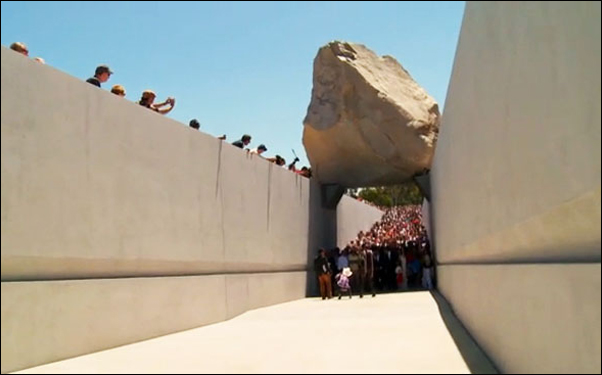

It is a different kind of rock being moved in his latest film “Levitated Mass,” which premiered this week at the Los Angeles Film Festival and makes an equally convincing push to be a quintessential Los Angeles film classic. Detailing the unlikely transportation of a 340-ton boulder from a pyrite quarry in Riverside to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in the heart of the city where it will become the centerpiece of Michael Heizer’s large-scale sculpture of the same name, “Levitated Mass” pulls off the extraordinary feat of illuminating the conceptual artist’s work, which has long dealt with the tensions between nature and industrialized society, without the artist present for much of its duration.

Instead, the film centers on the community effort that forms around the gargantuan piece of shale through a process that’s mired in bureaucracy and logistical concerns but ultimately results in a cultural event that pierces through the typically impenetrable veneer of metropolitan life. Over the 105 miles the rock has to travel, Pray captures the unusual sight of Angelenos lining up everywhere from Cerritos to Long Beach to watch a 206-wheel vehicle carry the rock as if the circus were coming to town. Yet it’s the people who Pray meets along the way who make “Levitated Mass” impossible to look away from, whether it’s the wealthy donors who helped fund the $10 million move to those able to watch it on the streets because they’re unemployed, the crackpots who theorize about the boulder’s possible alien origins to the naysayers who dismiss the rock as simply sediment, or the city officials who puzzle over how the move will affect their city as the residents see a rare opportunity to congregate as one.

Thanks to Pray’s film, this place and that moment in time have been captured forever and shortly before the film celebrated its world premiere, the filmmaker spoke about what led him to trail the boulder’s big move, discovering the unknown places in the city he currently calls home and what’s so special about this particular rock.

How did this film come about?

I got a call from Jamie Patricof, who’s the producer, probably two years ago and he just said, “Apparently, they’re moving this massive boulder, like way bigger than a house, through L.A. and they have to take down all the street lights. It’s for an art project.” And I just said, “Okay, I’m in. I want to film this.” [laughs] I really didn’t know anything about Michael Heizer and I was a fan of LACMA, but just like any casual Angeleno, so it was mostly just this idea of moving a big boulder, which I thought was cool because my dad’s a geologist. I grew up around quarries and have never done anything with it in film, but I thought that was a cool juxtaposition — a giant rock in the middle of this ultra-modern city. As the project developed, I got more and more fascinated in the actual art and Michael Heizer himself, so the film isn’t a biography, [but does] get into who is this guy Michael Heizer, who makes this big art, and why?

The film incorporates a few archival interviews with Heizer, but you spend very little time with him in the present day. Was that a choice to speak about him through his art almost exclusively?

I would love to say it was a choice we made when we began the project, but the truth is he really doesn’t actually like talking about art. He just likes making art and some people call him reclusive, but it’s more that his art is really, really loud and he just isn’t. So I had the choice of either only focusing on the boulder and what it did to these neighborhoods or doing some kind of a biography with no central character. As the project progressed, I felt like I could try to straddle both and in the end, I opted for a chronology that was reality-based. It started with the discovery of a rock, then how are you going to move the rock and fight bureaucracy and what happens when you try to make art that nobody understands because it’s so large? It just doesn’t fit into their preconception of what art could be. Then act two is the movement of this thing, which is really much more about L.A., technology and engineering this great feat and then act three, literally, is Heizer.

That’s how I ended up with this film and in some ways, it was a little bit schizophrenic because I wanted to tell the social documentary of the rock moving through neighborhoods and on the other hand wanted very much to do something where people could actually appreciate where Heizer’s coming from. It helps to appreciate the art if you do know some of Michael Heizer’s backstory from the 1960s and the more I’ve learned about him, the more I really like his art. What happened to me making the film is what I hope happens to audience who might come to it going wow, it’s about that big boulder and then in the end, they come out thinking wow, that’s really interesting art.

The film touches on a surprising amount of cultural and social issues, encompassing everything from concerns about the economy to religion, many of which are discussed by the onlookers. Did you have certain ideas before filming about what the movie would be about and did that change as you came into contact with people along the route?

There were all sorts of sub-stories. The biggest thing is just the idea that the rock is affecting people and I really liked the different ways that happened. There were people who took it literally as a religious miracle and there were people that took it as just a pure feat of engineering that could make them emotional. Then there were other conspiracy theorists thinking it can’t even be a rock. There’s got to be something else going on. So a lot of it was just entertaining.

I don’t want to try to sound profound here, but what kept happening was this idea that if art is what we make of it and if it’s something as massive as a boulder [hovering over] this 450-foot-long trench and you’re standing under this boulder [at the museum], it’s going to reflect on you. You can’t help but think about your life and who you are. There’s a couple quotes in the movie even like that. But it really is true. Good art is like a mirror. It makes you feel something about your own life.

What was cool was that the rock being transported isn’t really art, but it seemed to have a similar effect. I enjoyed that a lot. So whenever we heard stuff [about how] this is someone’s life being affected by this crazy thing rolling down the street, it made sense. Again, I can’t speak for Michael Heizer, and I’m sure he’s not that interested in what happened during the transport, but like someone says in the movie, “It’s our rock now. It doesn’t matter what he thinks.” To me, that is interesting and it is viable.

With “Big Rig,” you probably got in some good experience under your belt with how to frame such a large vehicle in transit. Was it a help here with the framing? There are some amazing shots, whether it’s inside a diner as the rock passes outside or my personal favorite where you see the tip of the rock hovering over a TGI Friday’s at night.

When I heard about this boulder, I really wanted to be in different homes or cafes — I wanted to get as many remote POVs as possible because there really were people sitting in cafes who looked over and there’s the boulder. It’s just the ultimate juxtaposition. I’m really into that and it was fun to plan out and think about, but mostly it was fun to just find them. We were just following the boulder and it was me and usually one or two other cameras, we just wanted to cover it in every way. I scouted the route quite thoroughly before, so I knew what was coming, like there’s this great rooftop or this cafe or there’s this valley or there’s these really cool oil pumps that we can see in the foreground, so I had a lot of fun visually. And with “Big Rig,” I wasn’t a stranger to large rigs moving and the idea of putting cameras on trucks. We had fun and we shot way too much, but that’s documentary. You just shoot a lot more than you need and the film looks a little better for it.

As an Angeleno myself, I always wonder about these places that are a part of the city, but I’ll never get out to. Was there one of them that you visited for the first time that came as a surprise?

The film is not in-depth enough to really have gotten into the communities as a true social documentarian [would have], but I just like the differences. When you go to Riverside, you really feel much more the history of L.A. because there’s ranches and goats and chickens. You feel much more like that’s what all of L.A. was like. It was quieter and that’s why that part of the movie is a little quieter. There’s that guy who has the little campfire by the side of the road and that wouldn’t happen on Western [Avenue]. I liked going into Rowland Heights [where] it’s fully Asian culture. You really just go through these neighborhoods and you realize the diversity of L.A. is not confined to the city of L.A. at all. It’s almost the opposite. Some of the suburbs are the most diverse places on the planet. It’s really interesting and you just couldn’t help but realize that when you are out there because the rock brought everyone together with total disregard of who you were. It was really an amazing cross-section. But to answer your question, I never quite knew there was a Bixby Knolls [in Long Beach] until the rock went there. They had this massive all-day long party. I was like, wow, this place has energy.

“Levitated Mass” will open in Los Angeles at the NuArt on September 5th before opening in limited release. A full list of theaters and dates can be found here. Of course, the “Levitated Mass” exhibit at LACMA is ongoing.