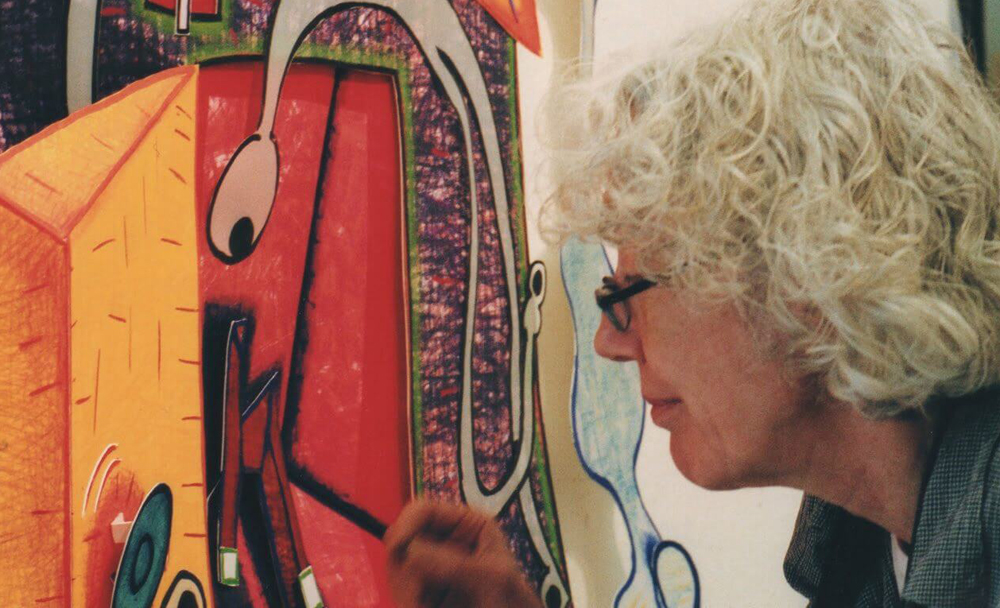

Kristi Zea knows about positioning things just the right way. One of the most sought-after production designers in Hollywood for the past three decades after coming up in the industry as a celebrated costume designer – you can blame her for the cut-off shoulder craze of the ‘80s after dressing the actors in “Fame,” her first film – Zea long had wanted to tell the story of a female artist in a way she hadn’t seen before — in full. While these women, who deftly maneuvered careers and their personal lives, were all around her, Zea only needed to take one look at the often unruly yet entirely captivating oil canvases of Elizabeth Murray to know she had found an artist who could eloquently express all the issues that women face in such a portrait.

“It’s so important to me that people understand all elements of this – the women’s issues, the family issues, the art issues, the period of time in New York — I was growing up in that time, so it was an amazing trip for me to take, revisiting the haunts of the Lower East Side,” says Zea. “It speaks to women like her, like me, who are trying to do it all.”

With such ambition shared by the film “Everybody Knows… Elizabeth Murray,” Zea’s documentary debut is as electrifying as Murray’s work, spilling off the edges as the artist’s oil paintings often do into every facet of her life that informs it, from the stylistic changes that set in from her move from San Francisco to New York, the revolutionary fragmentation of canvases that derived from the tension of starting a family while continuing to pursue a career, and the strong sense of humor and color that democratized her art, reflecting her desire to break it free of theoretical discussion into the human experience. The film surveys many of Murray’s closest friends and colleagues, but it is through journals (the words lovingly inhabited by Meryl Streep), interviews with the artist before her untimely death in 2007, and of course, the art itself, which Zea and her crew allow to envelop the viewer in their skillful use of camera pans and overlaid imagery that bring out the vibrancy of every brush stroke and brings the audience in thrall, as it would in person.

At just an hour long, the film is playing this week at Film Forum in New York, where programmers shrewdly paired it with Alison Klayman’s equally bold and affectionate “The 100 Years Show,” profiling the century-old Cuban-American artist Carmen Herrera, who has found success late in life for her geometric paintings that direct the eye to reimagine spatial relationships in seemingly simple design. While Herrera and Murray couldn’t be more different in their approach, the double bill illuminates a connection they do share in the unspoken but persistent activism inherent in their work and pioneering techniques which went unappreciated for far too long. Fortunately, with the two films now in circulation, proper attention can be paid and for the occasion, Zea spoke about her decade-plus struggle to get her film about Murray to the big screen, showing the practical life of an artist as well as her creative genius and how this truly special double feature came to be at Film Forum.

I’m actually pretty shocked when I think about it, but it’s been in process for 12 years. I was on a trip with Joanne Akalaitis, a playwright and director of plays, and she and I were contemplating creating a Mormon opera, if you please, so we were going out to Utah on research missions and we would usually include friends to join us. We would then go hiking in the canyons and have downtime with like-minded women dishing and downloading about our lives. Elizabeth joined us on one of those trips, like 25 years ago, and it was fantastic.

[The idea for the film] started to gestate [because] I do a lot of production design for directors of all kinds, including Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme, and both Jonathan and Marty did wonderful biographical docs about Bob Dylan and Neil Young. When I saw those, I said to myself, “Damn, I want to do a movie like that about a woman who I think is talented and artistic?” So I said to Elizabeth, “What do you think? Would you be interested if I did a documentary about you?” And she said, “I would love that.” She gave me a list of people she wanted me to interview and I, in turn, started to try to get some money to put it all together. The Warhol Foundation came through with a very sizable grant, which enabled me to get started.I had never done a doc before, but basically, we created these day-long interviews with all the people on her list coming in every two hours or so in front of a nice brick wall that a friend of mine had in his loft. That was back at the end of 2004 or the beginning of 2005 and then not too soon after we got started, [Elizabeth] realized that she had stage four cancer. Suddenly, things started to take a very different turn in terms of the kind of film we were doing and also how we were even going to do the film because we weren’t sure about how this was all going to affect her. Simultaneously, the Museum of Modern Art had been planning a retrospective of her work, so they started to kick that into high gear so she was going to be able to be a part of that and we kept going on. It all swelled into this gigantic effort with me interviewing her friends and her going to doctors and having all kinds of tests. Unfortunately, Elizabeth, passed away in 2007, so we had about two years of interviews and talking to her and being a part of her life.

It sounds like the focus may have changed before Elizabeth passed, but after, did you come to it with a different perspective?

It was a definite influence on everything. When she passed, we were all very surprised because she seemed to have rallied and [we] thought oh, maybe things are turning in a better direction, so when I got the phone call from Bob [Holman, her husband] telling me that she had passed in August of 2007, there was obviously a period of pause. But there was also a desire that this be done [because] now it was going to be about continuing her legacy. Many of her dear friends – people who she had wanted me to interview – were very upset by what was happening to her [at the end of her life] and really found it very difficult to be interviewed, but later [agreed], and in some instances, the conversations that we had when she was still alive are different than the ones we had with people after she passed.

We started editing the piece together and realized there were some question marks that we felt needed further explanation, so we [would do more] interviews later and then other things would happen like when the new Whitney opened, we found out that one of Elizabeth’s pieces was in the first show, so that suddenly became a big reason for us to scamper down to interview Adam Weinberg at the Whitney about Elizabeth’s paintings. When we found out they had about 45 other works of her art, that was very exciting and there would be different reasons why we would suddenly pick up the camera and add material. Some of the people age in front of you – from the time we started to the time we actually finished, it is 12 years – but a lot happened during that time that shifted the tone of the piece. It was a crazy process, I’ll say that.

One of the things I loved so much about this was the discussion of the practicalities of being an artist, which I think could only happen if another artist is telling this story. When you’re hearing the Museum of Modern Art’s director Glenn Lowery talking about the home/life balance…

One of the reasons why I wanted to do this film was because of the absolute conflict that a lot of women have between family, home and work, and how do you manage all of those things? How can you be a great mom, a great wife and a great artist? That was one of the first questions I would ask anybody who I interviewed, and men don’t necessarily have that kind of a problem as much as women do, so I loved that Glenn said the things that he said. What was also so great was that we also had access to all the family archives. Bob Holman, her husband, shot all of those wonderful films that you see, and he just said, “Take them all, use whatever you want.” So that was so much fun to go through all of these family films and take these great moments and pepper them in, like seeing those kids run through those big galleries with all her paintings behind them – [there’s a moment with her daughter] Sophie lying down on a blanket with her little feet in the air and there’s this monstrous painting behind her – that’s what I loved. I loved watching how a fantastic artist can also have a great life.

Regarding the archival materials, particularly the journals, did you know they’d be such a foundational element of the film?

Bob Holman was extremely open about it and he just gave me the key to the farm house and said, “You go up and pick the photos and you can bring it all back when you’re done.” And he let us take all of her journals – and there were like 80 of them – and we had those with us for a long, long time [because] I realized [when] we didn’t have Elizabeth with us any more, I couldn’t ask her any more questions, so the journals became a surrogate for her and we started to weave these bits of the journals as another character almost in the film.

In an odd way, it’s the voice of the inner Elizabeth and then of course, by luck and chance and probably some art goddess up there, I ran into Meryl Streep, who I had worked with already on “Manchurian Candidate,” at an Academy screening of another film and [when] I saw her, I said, “It’s really funny that I’m running into you like this because I’m doing this doc about Elizabeth Murray and there are these journals that I wondered if you might be interested in reading.” And she said [in a perfect Streep impression], “Oh, that sounds interesting. Send it to me.” I didn’t hear from her for about two or three weeks – it was around Christmas, so I thought oh God, she’s probably away for the holidays – but I got an e-mail from her, saying “I’m so sorry. I’ve been all over the place, but I’d be honored to read Elizabeth’s journals.” That just made my day, my week and my year and we arranged it so we had two hours of her time and she came in and did them all and it was the most remarkable thing ever.

It works so incredibly well. Did Elizabeth’s style of art inform the style of the film? I loved the way that images are overlaid in the editing and the way you’ll zoom in and out as if you were looking at a piece in person at the gallery.

Absolutely. [Elizabeth] said to me, “I don’t want a movie with a whole bunch of talking heads.” And I remember thinking, “Well, I’m going to need to have a few talking heads,” but [in terms of] embodying her work, I think what happens is when you get in front of one of these paintings, you don’t have a choice [in engaging with it] because you’re staring at it and you realize that it’s not just flat on the wall – it’s coming out at you, so you can walk around and see all the little different things that are at work. It invites that kind of exploration, so I would say to the camera people that I worked with, “Make sure you have a nice wide [shot] and a nice closeup, but just move around them and peek around the corners of them because that’s what they invite you to do.”

Even the sit-downs that you do have are lively. During a section on Elizabeth’s activism, you speak with one of the Guerilla Girls, who wears her gorilla mask for the duration. Was it even a discussion that she’d take her mask off?

It’s funny. We shot all of that at Joanne Akalatis’ house and when we were setting up for [the Guerilla Girl] to come over, we were wondering if she was going to walk in with the mask on. I kept thinking, “How’s this going to work?” But she walked straight in as a normal human being, and then I suddenly thought, “We have to protect her!” The reverence that you have for this group of women doesn’t go away, so when she put the gorilla mask on, there was a whole discussion about how we’re going to record her sound underneath a mask and there were some practical issues that happened – she got hot under there, so she had to take it off and walk around and we had some tea and water. [laughs] But it didn’t matter – she was just another wonderful human being, and when she put the mask on, suddenly this whole persona just happened. And I loved that. I just thought it was the best.

You directed another film before, but was doing a documentary any different?

It definitely was a new form of filmmaking. I’m used to getting the script, looking at it and deciding what you need to do. The thing about docs is that for the most part, you never know where it’s going to take you. You have a goal in mind, which is to tell a story about a given circumstance, whether it’s an individual or an event, but you don’t know how it’s going to unfold until you start to talk to people and really get into the nitty gritty. That was a little alarming at first because experienced editors and producers kept saying to me, “You’ve got to keep the camera going all the time. You never let it stop running,” and “when you’re doing an interview, even though you’re going to say thank you and cut, don’t cut, keep it rolling, because something could come out of their mouths when they don’t think they’re on the camera that’s better than anything that you’ve gotten!” [laughs]

There were all these kind of rules and I remembered all of those dos and don’ts, but when the bottom line came to putting it all together, it had its own flow. It also had its own length, which was another issue that has come up since it’s been done [because] a lot of people are terribly concerned about the length of a doc, particularly in view of the fact that docs are now so popular, they all have to be feature-length. At one point, I tried to make it longer and I kept saying this doesn’t push our story any further, so we just landed on [an hour-long running time] and no matter how hard we tried, it just wouldn’t get over 60 minutes. I just said that’s the length, and of course, that knocks you out of the box of just a regular theatrical run because most theaters in the United States, except for a couple of arthouses here and there are really chained to a 75-minute [or more] length film, but what’s really fascinating about the length that it is is that it made it possible for us to get the Carmen Herrera film to play with it at Film Forum and it’s an absolutely marvelous double bill.

It really is. How did you even know that was a possibility for you?

I’ve done three films with Brett Ratner as a production designer and when I was working on this Elizabeth Murray doc, I would occasionally come to him and say, “Aren’t you interested in this for Ratpac’s documentary group?” And he kept saying, “No, it’s too short. Netflix always wants them longer,” And I said, “Okay, fine,” and I went about my business. Then at one point, I was out in LA and he said, “Well, we’re doing this movie about a hundred-year-old artist,” and I said, “Oh, that’s interesting,” and when I was back in New York, we were on the warpath to find the other film to work with our film and I just texted him and said, “Brett, how long is this movie about the artist that’s a hundred years old?” and “Who is it?” [laughs] And so he said, “30 minutes. Carmen Herrera.” And he sent me a DVD and I looked at it and went, “Holy shit! This is incredible.”

At this point, Karen Cooper [at Film Forum] was also pulling her hair out because she wanted to find the right film [for a double bill] and we had been calling every film festival in the world to say, “Send us your shorts – any shorts that you’re going to screen or have decided not to screen. We want to see everything.” When we sent her “A Hundred Year Story” and suddenly, she said, “This is great. I think this absolutely works.”

What is the plan from here? You’ve said you’ve actually been thinking about pairing this with Elizabeth Murray exhibits – how do you see the afterlife of this film?

We don’t know which comes first – the chicken or the egg, but in this case, I think the chicken is getting the shows up in different parts of either the United States or Europe [but] mounting an exhibition is a long, drawn out affair. Up until the end of January, the Canada Gallery in New York is actually having an exhibition of her paperworks that’s on right now. Then at the end of this year, Pace Gallery is going to have a big show of her work as a kind of retrospective and we now have to run like bunnies to find out where we can actually screen the film while this is going on. This notion of combining the real art with the movie is a fantastic one, so what I’ve talked to my other producers and distributor about is hopefully being able to set up gallery or museum [screenings].

There was one experience I had like that at the OMI International Arts Center in Ghent, New York – I got a phone call one day out of the blue from the organizer up there because they were going to hang three of her works in their large gallery and she asked if I had a film. At that time, we had [an assembly of the film] that was about 20 minutes long and I said, “Would that do?” She said that could be perfect, so we brought it up there and of course the screening capabilities weren’t ideal because they didn’t have an actual theater, but we got a big television monitor, put it on a stand and screened the film. After we were done, we turned on the lights and the whole room was filled with Elizabeth Murray paintings. It was such a special moment. You just got up and walked over to the paintings and stared at them – right there! It was very, very cool.

“Everybody Knows…Elizabeth Murray” and “The 100 Years Show” are playing in New York at Film Forum through January 17th.