Sixteen films in and Klaus Haro still learned something new on the set of his latest “One Last Deal” – that making films in the present-day, his first, may actually be more difficult than setting them in the past.

“I was always thinking well that’s easy – we don’t have to come in here and redecorate if we want to do something, [like] a period piece. Hey, this is present day we can just shoot,” says Haro. “But in reality, it turned out to be much different. We had to ask for permission to do anything – we have trams that we stopped and we rerouted the traffic. That was new for me.”

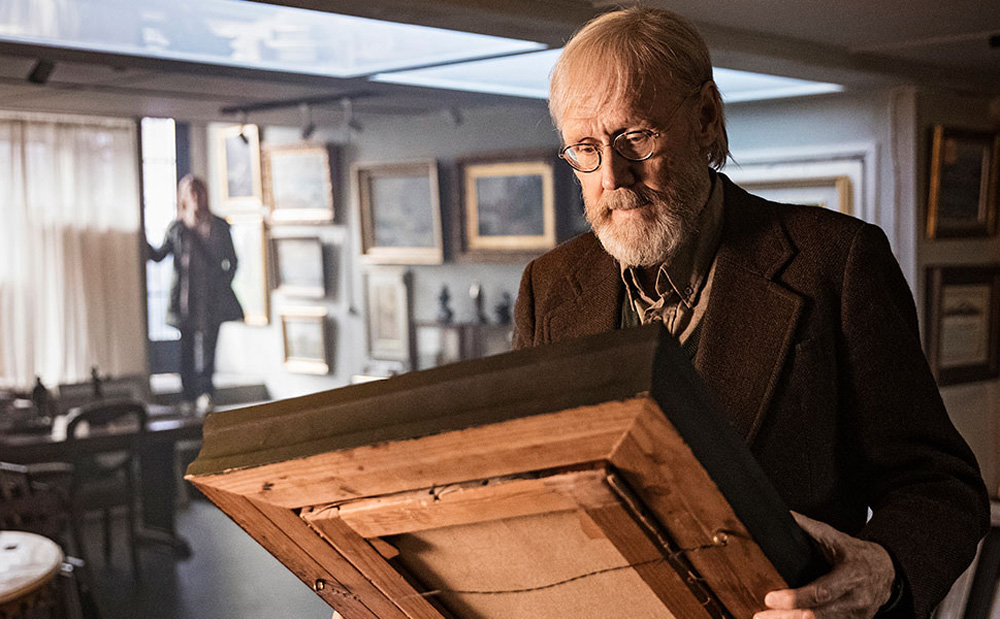

By comparison, Haro is a young man compared to the lead of “One Last Deal,” but the director could relate to having a new experience well into his career as he tells of Olavi (Heikki Nousiainen), a 72-year-old art dealer who isn’t quite ready to head into the sunset despite flailing business. Located next door to a thriving auction house in Helsinki, his eye is drawn towards a painting known only as “Portrait of a Man by an Unknown Master,” though his years of the expertise lead him to have an inkling as to who it is. Although it becomes clear that Olavi could retire happily if he could lay his hands on the canvas, the path to doing so gets complicated, particularly when his daughter foists his grandson Otto (Amos Brotherus), in need of fulfilling some work requirement, to help out around the shop. Still, things go better than planned when teaming with the feisty 15-year-old, searching through old museum catalogs and scouring Finland for clues to the painting’s origin, and as Olavi gets closer to confirming his suspicions before placing his life savings on the line to buy the portrait, he begins to realize the distance he’s placed between himself and his family over the years and all the lost time he’ll never be able to recover.

Haro, who last directed the Oscar-nominated “The Fencer,” knows how to make a crowd pleaser able to wring tears without ever being too sentimental and building upon the punchy rapport between Olavi and Otto, “One Last Deal” is savvy at sneakily tugging at the heartstrings while delivering a diverting caper-sequence adventure, not unlike how the art dealer finds himself more emotionally entangled in his latest acquisition than ever before. Shortly after the film premiered at the Toronto Film Festival, Haro spoke about how he got hooked on “One Last Deal,” reuniting with Nousiainen a decade after their last collaboration and the trick ones of a work/life balance.

It would be so great to say that it was my idea, but it was not. It was Ms. Anna Heinamaa. When we were working on “The Fencer,” she was telling me about his idea she was working with about an elderly art dealer who wants to do one last deal before he retires, and needs to do it in order to prove himself.” It happens rarely, but right then and there it happened like in movies – she said this sentence, and everything goes silent. I’m just thinking, “Did you already give that to some other director or would it be available?” It was only an idea, but she has an extraordinary eye for what works in a movie and what doesn’t, and I thought this was a very classical theme. She knows the art world, she has a past in dealing with art, so like “The Fencer,” she writes about what she knows. So this movie is her baby, and I was happy enough to be able to go along.

Still, there seems to be a thematic connection to your 2009 film “Letters to Father Jacob,” where the central character is torn between their professional calling and their personal responsibilities. Was that important for you to explore?

Certainly, there is the issue of looking for self-worth in what we do, and in “Letters to Father Jacob,” it was very much about, “Are we what we do?” or “do we have a value in ourselves without achievements? Who are we when we can no longer buy our place in society with what we do?” Often, we judge ourself on our worth, but if something happens and we can’t work anymore, does it change the way we perceive ourselves? Maybe it shouldn’t be that way, but usually it does. So if you retire, it’s a big change in your life, but does it take away who you are? It shouldn’t, even if it’s another kind of crisis for sure.

And of course, I got to work with a favorite Finnish actor of mine, Mr. Heikki Nousianinen, the art dealer in our film who played the priest in “Letters to Father Jacob.” For me the Henry Fonda of Finnish cinema. He is a wonderful, most humble man to work with and whatever he does he does it with such subtle intensity that it will draw you to the screen when you’re watching. So skilled and in Finland, actors usually work in theater and then they do film in between. He was in the theater for more than 40 years, and I tried earlier to get him in my films. And he was always, “I can’t, I’m in the theater. I can’t.” Then he retired and we were able to do “Letters to Father Jacob” and he’s been busy ever since, so now 10 years later, I said to him when we wrapped the movie, “I hope we’re doing a film again in 10 years from now.” Regardless of what that movie is, I’ll find something so I can work with him.

He has a great rapport with Amos, who plays the young man Otto. How did you cast him?

Otto [came through a] more traditional casting call for young men. Very early on, our casting director said, “Look, I’ve got a young man here. He might not look like Otto in [your] mind, but I think when you see this guy you’re gonna like him.” He certainly had that innocent charm. At the same time, he has a hard time sticking to the truth and it makes him charming, but also it makes you a bit worried at how’s this young man gonna do, so by the end of the movie we’re thinking, “Okay this young man is gonna do good.”

And they had a great chemistry. You never know. I’ve made films where you have a couple and they really can’t stand each other and then they’re supposed to be in love once the cameras are on. But we had rehearsals and I would soon find out that Amos [who plays Otto] was very inventive, as was Heikki. Heikki’s 73 and was just bursting with ideas and so full of energy, so they would very soon find a chemistry. What I found out as a director is if you get a thing going between two actors and they find a chemistry where sparks start flying, you should not go in there and mess with things. If it works, very gently you can direct them in some direction, but let that be what comes out in the movie. And certainly what you see there is, behind the scenes, is that they had a good time together and they would get along really fine.

There’s so much art in the film. What was it like to do the production design on this, filling all this spaces?

The shop itself is a built set, and the idea of the film is not that [Olavi] is into very valuable art. The reality is that he deals quite mediocre art. That’s his everyday business. Maybe he used to be on another level earlier, but now he’s dealing with whatever he can get his hands on, so this painting he finds is something different. That’s the painting that will take him to the next level, so the art is not that valuable, but it’s a big job. What was more challenging was going to the Finnish National Art Gallery [for] a scene where they’re looking at the paintings, comparing paintings and talking about prices. At first, the Finnish Art Gallery said, “These paintings here don’t have a price. They’re not for sale.” And we had to explain to them, “No, we’re not saying that they do, we’re just supposing if they were for sale.” So we had to convince them, but they were very generous with us. Of course there were huge paintings that [had to be] removed for us so we wouldn’t hit them with a lamp or with a tripod. They’re not the Mona Lisas exactly, but close to that in Finnish measures, so it was like shooting at a church where you feel like there are things that you have to watch out for.

It’s the Finnish National Archives actually. bit it’s supposed to look like an art gallery library. Often in movies, you have to just go for what location gives you the right impression and the Finnish National Archives is this beautiful old building from the end of the 1800s [where] they have these books that are like these big refrigerators. It’s a huge, beautiful place.

Was it interesting for you to have to tell the story about the commodification of art?

It was, first how can you put a price on art, but then if you don’t put a price how can I tell its value. But more than that, it’s really about if we got a second chance, would we able to take it? Everybody says more or less, “I wish I could do that again,” but if we could go back in time and we could redo things, would we able to do that or would we make the same mistakes all over? This is a man who gets a new chance late in life to reconnect to his family and he’s basically lost because he’s a workaholic. His passion for for the business in art, dealing in art is like gambling. And that’s how we thought of it. And you might say to your family, “I won’t gamble anymore,” but then you have a casino there and it takes a lot from you to resist if that’s your habit. So he’s fighting against old habits which is tearing back to his family.

This is a beautiful score.

Matti’s a composer I’ve been following for a while. He did live [scores] with his band where they were playing silent movies — that’s how he started some 15, 20 years ago. And he’s done quite a lot of scores in Scandinavia, and I wanted to work with him for many films, but only now did we get a chance to do it. It was wonderful. He is so sensitive and he was so committed to the movie. At the point when we’ve shot the movie and we’re editing, I might get a little tired and he would give me so much energy with his commitment to the film. He’d say, “Oh, I love the faces of these actors,” and he would be so inspiring to me. That’s how working with film is when it is at its best. The writer will inspire me, I will inspire her, and then her writing will inspire the team. It’s not always like that, but with this particular movie it was. We would inspire each other.

What’s it like getting to the finish line?

I’m always anxious. Even before you get any reviews, it’s done for me in a way [since] I’ve seen it already 50 times before it comes out. I’ve seen it with the editor, I’ve heard the producer’s views and I usually bring in some intelligent friends to see the film and give me some criticism before we lock the cut so we can still change things and make them better. Of course the Toronto premiere was big for us. I was here 12 years ago and I remember that the audience is very attentive and they are people who are interested in films. They are very particular, they choose the kind of films they wanna see and they’ll tell you if they don’t like it. [laughs] Yesterday, I had four or five people coming up to me saying that this was the best film they’ve seen in the festival, or even that they can remember. People were really generous, they were crying because it’s a very emotional film, and for me, film is very much about sharing. It’s not about me telling you how things are, it’s about me telling you this is how I experience things, do you share this? Do you see things the way I do? Now, meeting the Toronto audience, it’s the high point of the journey to be able to come here and share the film with this beautiful audience.

“One Last Deal” does not yet have U.S. distribution.