“Welcome to Bomber Territory,” it reads above Richland High School football field in Richland, Washington where the school’s mascot is intended to honor the history of the area, home to a middle-class community that could count on a steady paycheck as an industry town at the service of the U.S. Department of Defense during World War II, creating plutonium for the possibility of nuclear war. One might think a mushroom cloud might be the last association anyone would want, but here it is adorned to varsity jackets and helmets when it brought prosperity and there remain plenty with parents or grandparents that worked in the factories, handling the hazardous material but able to provide for their families.

Irene Lusztig isn’t one to take away from the region’s civic pride in “Richland,” observing the festivities on the 75th anniversary of the Manhattan Project during Atomic Frontier Day in 2019 and walking down streets in Richland and the adjoining town of Hanford such as Proton Lane to meet with locals who generally make light of the town’s main claim to fame. But there is quite literally something lurking underneath the surface in a place where gardens cannot grow and although atomic age recreations such as bowling alleys persist, they host cancer fundraisers for people who appear too young to have such concerns. In reflecting such a complicated place, made more so by the fact that it’s real estate that indigenous communities have a rightful claim to after it was appropriated by the U.S. government, Lusztig takes the simplest and most direct approach to giving a lay of the land, gracefully moving from one part of the community to another to learn of their connection to the town’s history, with quiet encounters in cafes and outside homes showing the profound reverberations for better or worse that plutonium production within their city limits has wrought.

Both an entertaining portrait of a unique burgh and a fascinating consideration of how people appreciate their present comfort versus confronting an uncomfortable past that can’t be easily rectified, the film not only digs deep into Richland history, but serves as a showcase for the depth that Lusztig’s unconventional approach can yield from people who might not otherwise have the opportunity to give such thought to their surroundings. With the film recently making its premiere at Tribeca, the director spoke about how one film has led to the next, both in terms of subject and her distinctive style of filmmaking, as well as how she found ways to start uneasy conversations and brought a little bit of harmony into the film.

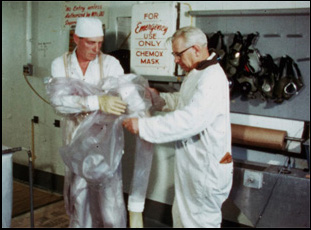

Yeah, my previous feature film was called “Yours in Sisterhood” and it was a road trip film that I was filming all over the U.S., following the trail of these letters that I found in an archive that were sent to Ms. Magazine and basically, I was showing up in communities one after another. I had found a letter in this archive from the ’70s that was written by a daughter of Hanford workers that talked about losing her dad to radiation-related exposure. [Initially] the project was inviting people to perform these letters and respond to them and I was doing a lot of matchmaking, looking for interesting people to read different letters. Someone connected me with Trisha Pritikin, who was the first person I met in Richland and she’s a downwinder activist, someone who grew up in Richland, and also lost her parents who were Hanford workers to radiation-related illnesses, and suffered from a lot of illnesses herself and she read this letter [for “Yours in Sisterhood”], but also really generously drove me around town and showed me around a little bit. She showed me the house where she had grown up and also led me behind the high school to where there’s this 40-foot mushroom cloud that you see in the film that’s the Richland High School logo, which is where she wanted to be filmed for “Yours in Sisterhood.”

I was just there for a day in 2015, but it really just really stuck with me as a place I had a lot of questions about. I tend to make work and be interested in spaces where it feels like there’s some kind of unresolved history or questions about the past that feel very present in terms of how people are thinking and wrestling with things. So I had a lot of questions about what is this community that has a nuclear weapon as a heritage symbol, especially as the Trump election happened and conservative nationalism became more and more visible as a really powerful force in the U.S. My curiosity about Richland started to feel connected to a lot of these bigger questions about what are the structural forces that shape conservative worldviews.

It’s interesting to hear of the letters being a facilitator for conversations because in the film, you use the poem “Plume,” which seems like it gets the ball rolling for a lot of people to speak to their own experiences. How did that text come to the fore?

I’m really interested in the way that a performance or something called a performance in a documentary can just just create more agency and more of a participatory space with people and with community members, and pretty early in my research, I had read “Plume,” this book of poetry by Kathleen Flenniken, who’s also from Richland, and initially, I would just try to have people read it, curious if it would bring stuff up for them and in the film, it does this work of bringing the community into this more active space of choosing the poem [within the book] and thinking about how they’re finding themselves in someone else’s words and I think it shifts a the power dynamic a little bit of what might happen in a more conventional documentary.

Was the film ultimately reflective of your own experiences of the conversation that was happening in the community when you filmed over so much time?

It’s not 100% in chronological order, but the structure of the film definitely moves into more and more complexity, but also more and more intimacy with people and I think some of the most moving narratives or testimonies in the film happen near the end. That was true to my process that it took a while to get there with people, and I hope people have that experience when they watch the film that they come into thinking about a community like Richland with a lot of knee-jerk reactions or preconceptions or ideas of what think a weapons production company town might be. But I hope that as people watch the film, they also move as I did into a space of more and more complexity, holding a lot of different perspectives and points of view.

I tend to go into a project not with any kind of fixed idea of what I’m going to find or even what the film is about, and I want that as I’m working. I hope the film feels like that. Constantly, I was pushed to change my views and think about things in new ways and certainly I didn’t know very much about nuclear things before I started working, so there was a huge learning process that I had in terms of understanding the subject matter and Hanford history. It’s both simple and complicated, but my biggest lesson was that if you listen to people with generosity, you can create a really meaningful conversation space with all kinds of people, including people that might initially seem to be very different in their politics or their lived experience. That was was a commitment for me from the beginning of the project that I wanted to challenge myself to spend time with people who maybe were more conservative or had a different viewpoint, but to do it in a way where we could just make a space where we were listening to each other.

It seems to move from individual conversations to group talks towards the end. Was that a different way of engaging with people?

Maybe there’s intimacy that can happen when you’re one-on-one with someone that’s a little different, but on the other hand, there’s a dynamic in the group and that can also be a conduit — like the guys playing cards in the Spudnut shop, that was just random and we just got very lucky. We were doing something else in that diner and they play cribbage together every week and have done forever, and I think just that relaxed banter between them came from how comfortable they are with each other. But there’s different kinds of intimacy that can happen in both kinds of spaces and some of the spaces in the film are more public facing and those also feel different. I was interested in looking for and threading through the film spaces that felt different, either [in terms of] storytelling about history in different kinds of ways or thinking about reconciliation with the history that’s difficult.

You also shake things up with a few curveballs like the singers that you get out onto the highway. How did that come about?

That’s funny. Those women are in a band called Trillium 239, which is a Richland folk [group] and it’s actually a trio, but the cellist got COVID [before our shoot], so I ended up just filming with the two of the women and Mary [Hartman], who plays the banjo is a Hanford hydrogeologist, so she’s also a Hanford worker, and they have a real personal connection to the song [they’re playing]. But I actually learned about this song from those guys playing cribbage in this Spudnut shop. [One of them] sings a capella “Termination Wins” [in the film] which I’d never heard before, but then of course I went home and Googled it and then found a YouTube performance of Trillium 239 doing this [song], so then I just reached out to them [asking] “Do you want to make a weird music video with me where you play the song?” And they were very cool about it and up for it.

What’s it like to have the film at Tribeca?

It’s been amazing to get into Tribeca. I’ve made work for 20 years, but I work extremely independently and I’ve been a little bit uncompromising in terms of thinking about form and really just making work the way I want to make it, so it’s really fantastic to get into what I think of as a mainstream festival. And what’s most meaningful to me at the end of the day is for the community to really feel good about the project. That’s been incredibly gratifying. People from Richland who’ve seen the film so far really love it, and really feel like it’s as complicated as they understand their own history to be. There’s a bunch of Richland folks coming for the [premiere] and Kathleen [Flenniken], who wrote “Plume,” and Yuki [Kawano], who made the amazing sculpture at the end of the film, is coming, so hopefully [screening it] will feel just like a special moment for Richland of being seen in a way that’s more complicated.

“Richland” will screen at Tribeca Festival at the AMC 19th St. East on June 14th at 8:15 pm.