It wasn’t the lurid details of the Jerry Sandusky sex abuse scandal at Penn State that first caught Amir Bar-Lev’s attention as a filmmaker. It was everything that came after, including the riots that took place in State College, Pennsylvania after the school’s legendary head football coach Joe Paterno was relieved of his position after 45 years in which students made their feelings known towards the Board of Trustees who dismissed him and the media that flooded into town to cover the crisis by flipping over a news van.

“It was the first riot in favor of authority that I can ever remember hearing about, so I thought that’s interesting,” says the director, who returned last week to State College to present the film at the town’s State Theater. “I needed to find out some more about it.”

What Bar-Lev found was a far more nuanced story than the one that oozed out of Penn State in the immediate aftermath from the revelations that Sandusky had used the power that came with being an assistant coach in the football mecca to take advantage of the young boys who had passed through his charity’s summer camp. Though Bar-Lev would interview a number of key figures in the investigation, including Sandusky’s adopted son Matt, who became a pivotal figure in sending his father to prison, Paterno’s wife Sue and sons Scott and Jay, as well as three of the victims and deposed president Graham Spanier who didn’t make the film’s final cut, his aim with “Happy Valley” wasn’t to chronicle the stunning crimes that were committed or to assign blame to those who might’ve known about Sandusky’s transgressions, but instead to examine the culture that gave such clout to Sandusky in the first place to feel as if he were above reproach.

As in his previous films “The Tillman Story” and “My Kid Could Paint That,” Bar-Lev explores society’s tendency to create idols to fit their own needs rather than reality, but elides the easy explanations for how this happens in favor of witnessing how people rationalize what they know to be true with what they’d like to believe. However, once more, the filmmaker doesn’t only engage with audiences by allowing them to come to their own conclusions, but also in the entertaining ways in which he explores that duality, discovering perhaps the most perceptive critic at Penn State is one of its youngest and most die-hard fans in 2013 graduate Tyler Estright, and that a mural in the town’s center once extolling the virtues of Sandusky and Paterno has been turned into an ever-changing canvas that reflects the community’s continual soul-searching. While Bar-Lev was in Los Angeles recently, he spoke about the mural, why he’s no longer daunted by following subjects that have already endured extreme media scrutiny and how his ideas about “Happy Valley” changed as he made it.

I make these movies because they can be good exercises in building empathy. For me, the story that seems to be the most efficacious in building empathy was the story of the people who might have been able to stop this, but didn’t do enough for reasons that, to my mind, don’t have to do with protecting the Penn State brand or Jerry Sandusky or trying to maintain revenues for their football program. Rather, they’re much more commonplace – the idea of seeing, but not seeing and willing oneself to push to the periphery that makes one uncomfortable. Those are things that I think we’re all guilty of and I’m interested in the failings that I have that are a part of all us. That is what’s worth it for me to spend two years doing it, so it’s worth it for my audience to spend 90 minutes watching.

When you went down to State College, you weren’t the only camera there. Was that a different experience for you as a filmmaker?

I’ve had this experience on a number of films because I tend to choose subject matters that attract a lot of cameras. But a long time ago, I had a lesson once in not backing off. I read “The Lost Boys of Sudan” article in the New York Times and by the time I got around to calling the requisite people, they said “Hey, get in line, there’s 11 people in front of you.” I [thought I] missed the boat, and when finally a film or two came out about that subject matter, I realized that they had actually looked into it after I had made that phone call, so it was a lesson: never back down if there are other cameras swimming about.

Obviously, there were plenty of news cameras, but my other takeaway from doing this a few times is that those news cameras are gone not long after the event, so if you just have some patience and stick around, people will see that you’re there to tell a story in a far different way than the news tells it, and you’re going to have patience to hear them out in a way that the news won’t.

I felt it was an incredibly wise decision to focus on the community rather than the investigation. Was that where your thoughts for the film began or did it evolve over the course of making it?

It evolved. It feels like everybody says that, but in my opinion, if you come in with too many preconceived notions, you’re not going to make a good film. I chose to look at the cultural aspect of this because I’m interested in lessons and truths that are universal. Watching what happened as their sense of identity shifted in Happy Valley, as the person who they had held as the “town father” [in Joe Paterno], the paragon of the town’s values, as they reassessed him and his legacy, it felt like this story touches on some paradigmatic truths.

Just before November 2011, having a Joe Paterno T-shirt was like having a Santa Claus T-shirt. It meant that you were embracing the values of a beloved, avuncular figure, but by the time we were midway through shooting, having a Joe Paterno shirt would be the equivalent of having a Judas Priest T-shirt. It was a kind of “fuck you” to the rest of the world. That’s interesting for me, because what I like to do with documentaries is cultural anthropology and to watch the semiotics of a Joe Paterno shirt change from Santa Claus to Judas Priest was fascinating.

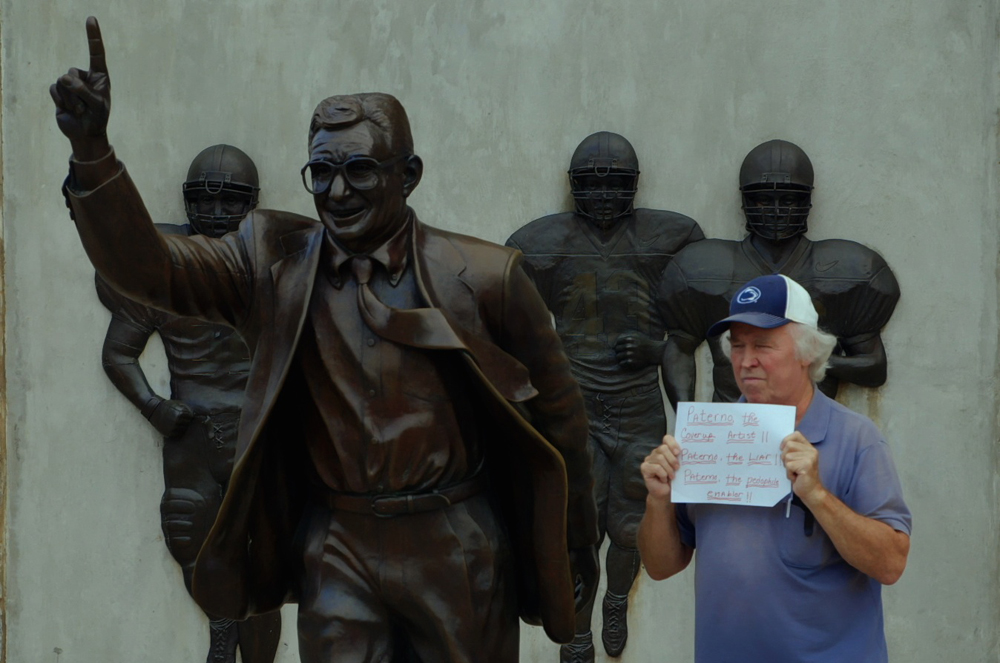

I can’t imagine a documentary filmmaker seeing that mural being revised and not instantly understanding that that was something one needed to track, for the reasons you already said. It’s a story about a town reevaluating its mythology, and the mythology was enshrined in this almost a totem pole of a mural that had all the town’s paragons enshrined on the wall there. Of course the first thing they did was to paint Jerry Sandusky out and [between that] and the knocking over of the Joe Paterno statue, it is a living, breathing example of the way that we change our mythology when it no longer works for us.

There does seem to be a connective tissue across your non-music nonfiction features in terms of having this collision of what people want to believe versus the reality of the situation. Is that purely coincidence or is that something of continuing interest?

It’s not coincidence at all. I think, whenever possible, human beings live in a symbolic world and they are more comfortable with their symbols than messy reality. “My Kid Could Paint That” was about the collision between our sense that Marla Olmstead’s paintings were the embodiment of innocence and childlike wonder and reality. “The Tillman Story” was about a family trying to rescue their son from the Hero myth that has fossilized around him and stripped him of his reality, or stripped the family of their ability to connect with who he actually was. Even “Fighter,” my first film, was about two older guys making their way through a road trip and one of them is challenging the other guy’s crystallized memories, which have perhaps strayed from the reality of what happened to him in World War II.

“Happy Valley” is about the collision between the father myth and actual fatherhood. It’s about a town realizing that their symbolic father is actually a human being. All of us have that moment where we realize our fathers are not these towering figures that can protect us from the world. We all get to a point where we realize that our fathers are frail and can also make mistakes and that the outside world can get to us. That’s what happened in Happy Valley.

“Happy Valley” is now open in New York at the Cinema Village and will open in Los Angeles at the Royal Theater on November 21st before expanding across the country. It will also be available on VOD on November 21st. A full list of theaters and dates is here.

Comments 1