It is rare for a biography of a deceased subject to feel as if it’s speaking to the present moment, but then again Stieg Larsson, who enjoyed his greatest success with “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” from beyond the grave, was always ahead of his time. With “Stieg Larsson: The Man Who Played With Fire,” director Henrik Georgsson fashions an invigorating profile of the late writer that feels like it could easily be an additional chapter for Larsson’s “Millennium Trilogy,” in which he drew upon decades of experience as a journalist tracking far-right movement in his native Sweden to craft a bewitching crime saga in which he could channel his skepticism towards authority into Lisbeth Salander while getting the details of the tireless muckraker Mikael Blomkvist just right.

While their adventures tracking down a serial killer already captivated millions, Georgsson reveals that Larsson had perhaps an even more fascinating life, albeit one spent largely behind a desk. After being raised largely by his grandfather who was imprisoned during WWII for speaking out against the rise of Hitler, he set about tracing the insidious forms that Nazism began to take around the world once shame and defeat had forced it underground until it could be brought back into the mainstream. Tracing the CD pressings of a white power band called Ultima Thule that was embraced by the far-right party New Democracy in Sweden, Larsson found an international conspiracy that sought to undermine democracy and would tirelessly record his findings for Expo, a magazine he started in 1995.

Burning the candle at both ends — writing “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo” started as a way to simply blow off steam after hours — Larsson died far too young at age 50, but as becomes obvious from the friends and family Georgsson speaks to, the reverberations of his life and work continue to ripple through their daily lives as it does us all when the global resurgence of neo-Nazis and authoritarian leaders has made it sadly all too relevant. While Georgsson was at Sundance for the film’s premiere, he spoke about being thrust into his own globe-trotting thriller in connecting all the dots that Larsson has so diligently uncovered, sifting through his voluminous archives and the unusual ways he found to defend himself against death threats.

Everyone knows Stieg as a writer of crime novels, but It was just writing the books the last two or three years of his life. And actually, [the film] started off in another direction. We had an assassination of a prime minister, Olof Palme in 1986. Stieg was interested in that because they never found who did it in Sweden, and it’s still unsolved, but he was looking into it and we had an idea to do a film about that, but when we did research, we thought it was more interesting to do a film about his interest in the extreme right because that was the subject for most of his life and it was a relevant story to tell now because there’s so many movements in that direction in Sweden and the rest of the world.

Did that relevance shape how you wanted to tell this story?

Yeah, for a while, we were thinking about including the present time a little bit more, but because he died in 2004, we didn’t want to go on because then we would lose Stieg’s perspective in the film, but it was very interesting because [going through his archive] was like going through 30 years of Swedish history and European history. He was into a lot of things and he was really a researcher that collected things and just knowing about things [was a passion]. In the beginning at least, that was more important than telling other people about it.

Was there any artifact that really opened things up for you?

He did these maps where he had circles around names and drawing arrows to another circle of names [where] he put the names on the organizations and he [drew] the line to who they were connected to in different countries. Actually, he had a document that was put together from I don’t know how many [other] documents because it was like two meters wide and four meters long or something like that — he put it out on a board and then he had all the organizations and the names of the extreme right in Sweden and Scandinavia and Europe and all the connections to U.S. That was kind of crazy. When we found that, we felt like yeah, we have to do this because he’s so obsessed with these organizations.

There are at least three journalists with their identities concealed – was getting their participation tricky?

Yes, one of them is from Searchlight, a sister magazine to Expo, which Stieg started, and he’s living under death threats and the other two were tricky to find actually because they’re hiding out.

Off course, we wanted it to be thrilling in a way, but we didn’t exactly try to copy the style from the Fincher movie or anything. But there was suspense in his life because of what he was doing and he was working undercover, so there were threats. There were several things of course that we didn’t know about him and one funny thing I think was that he taught his colleagues at Expo how to protect themselves if they got attacked in their homes, creating these small weapons to use in their tiny apartments. He thought that everyone should have a baseball bat at home if someone attacked them at home and they lived in such tiny flats [that] he had to create smaller baseball bats so they wouldn’t hit themselves in their heads or their walls. He wasn’t a pacifist in that way. He thought if someone attacks you, you have to fight back. But otherwise, he was friendly and he was a journalist. He felt it was important to separate those things from each other. He was looking for facts. He was very careful with facts.

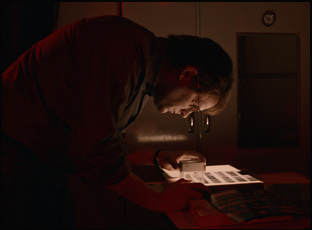

With the interviews, we [also] tried to create a mood in those pictures. It wasn’t really important to us where they were or how it looked in their home or their office, so we tried to make that fit into the overall tone of the film, some kind of a thriller feeling around the pictures. I usually do more fiction/drama series, so I could [also] work with sound in a creative way, even if it’s a documentary.

What’s it like getting to the finish line with it?

It’s exciting to see if it works with an international audience. It’s really a story about Sweden mostly, but to see it’s attractive to people in other countries [has been] very interesting to see how that works.

“Stieg Larsson: The Man Who Played with Fire” does not yet have U.S. distribution.