In the early moments of “Free for All: The Public Library,” co-director Dawn Logsdon recalls when a hurricane blew through New Orleans when she was just a child in the 1960s and her mother dutifully raced out for supplies, not from the local grocery or hardware store, but rather the library where she could pick up “The Little Engine That Could” to read to her kids to keep them occupied while the storm blew over. It was a memory that the filmmaker would hold onto forever, but was particularly vivid when it seems as if storm clouds have started circling again around public libraries far and wide, a place that was long a place of comfort for Logsdon, but in recent years has been under attack by conservatives who have wanted to cut funding and remove books seen as controversial from the shelves.

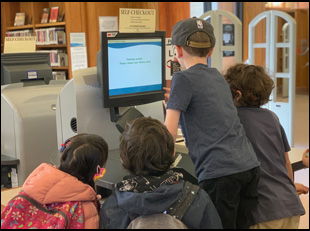

The fear that this grand American tradition of offering free access to a wealth of information was enough to push Logsdon to start out on a decade-long, coast-to-coast journey to capture how vital an institution public libraries remain for so many communities across the country. Ultimately bringing on a co-director in Lucie Faulknor for the doc, the filmmaker shows opera singers belting out from the rafters at Salt Lake City’s cavernous central literary hub, dance classes in San Francisco’s state-of-the-art facility and the Muehl Public Library in Wisconsin where the Kirschberg family of 19 regularly pile in to supplement their home schooling with a mountain of books to carry home.

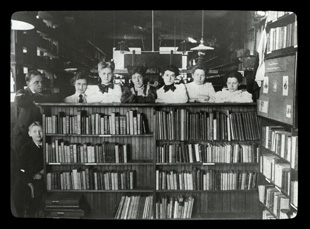

As immigrants are made to feel right at home at the Seward Park Branch Library in Queens, acclimating to the culture, the library system looks to be one of America’s greatest achievements as an egalitarian ideal in “Free for All.” Yet as the film reminds, the tough times they face now are not a new phenomenon when libraries have long been a barometer for social progress, largely built up as a practice by women who were once forbidden from accessing them for fear that they might be as knowledgeable as their male counterparts and further made a measure of equality as they became desegregated as a result of the civil rights movement. Logsdon and Faulkner make a strong case for why people should continue to fight for the freedom of libraries when celebrating so many that have in the past, singling out a number of crucial figures in their development who saw a cause much greater than themselves in fostering such a central public space and while the filmmakers show the demands placed on library staff has dramatically changed, the purpose that has inspired so many hasn’t wavered.

In the same spirit of the libraries that open their doors to all, “Free for All: The Public Library” is making its debut tonight on PBS’ Independent Lens where audiences far and wide can enjoy a magnificent history and Logsdon recently spoke about putting the film together during a turbulent time for libraries and the U.S. as a whole, discoveries made along the way and finding that putting herself into the film was the best way to tell the story of a public space that has touched so many so deeply.

Because people were telling me that we don’t need libraries anymore. I kept hearing that over and over again. The country was just coming out of the recession at that time, and libraries were actually full of people. They were at their all-time high in terms of visits. But that’s not the story I was hearing in the news, which was more like, “Oh, they’re obsolete. They’re just about the printed word. We don’t need books anymore.” Budgets were getting slashed as a result, so I wanted to highlight how important they have been in our past and how important they still are today.

I saw an initial pitch for the project that seemed very different, where it was going to follow various people in the present. How did this evolve?

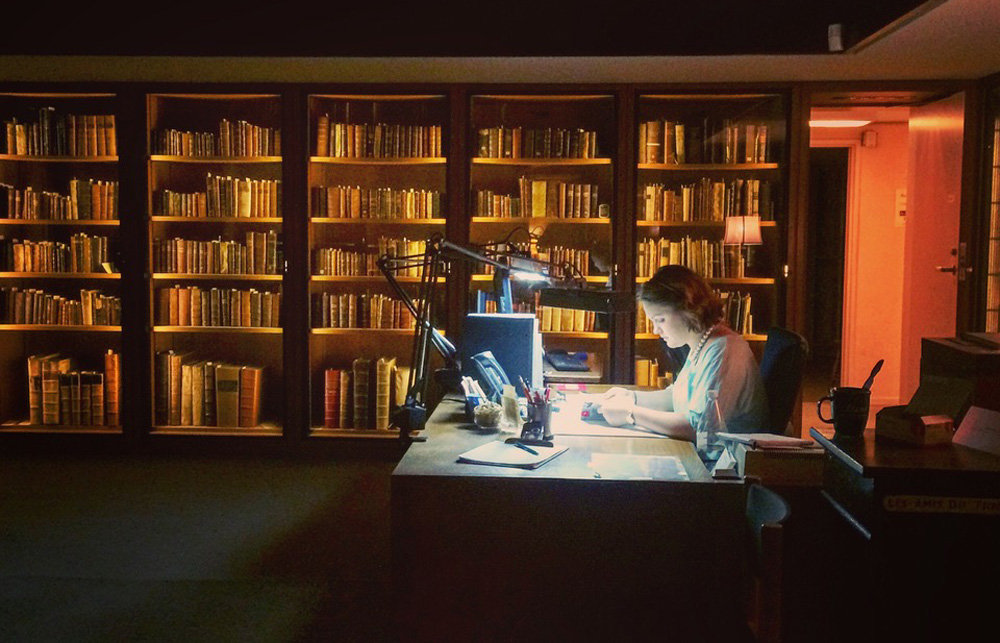

Totally different movie. The spirit of the film is still the same. But what happened is I fell in love with the history. As we traveled around and we’re filming these contemporary stories, I was just like, “Wait, let me just spend a little time in the archives.” I’m a history buff, so the more I learned, the more intrigued I got and I was especially fascinated by how many of these battles keep coming around. A lot of us thought book challenges and censorship are issues that a lot of us have resolved in our own minds a while ago and that we think are part of history, but they’re not. They’re always with us and they keep coming, popping back up. Same with women’s role in society and their role in shaping the library, and then who’s allowed in? Who’s welcomed? Who’s not? Whose ideas are allowed in and welcomed and not? And I found that storyline taking over the whole film.

And for some reason at the beginning, I wanted to not have one central character tell the story, but to have the institution be more of the central character. But that’s a really hard thing to do in one documentary. The way we ended up tying it together was having me be the thread that guides us from one story to another, even though there are all these amazing, fascinating men throughout library history to try and tell the story mostly of the women who played really critical roles and who’ve been totally forgotten.

Were you planning to have as much of a presence in the film as you ultimately do?

I am like the last filmmaker who ever wanted to put herself on the other side of the camera, and I went kicking and screaming. If it had been a different filmmaker, we probably would have finished this film a long time ago because I was resistant the entire way. Fortunately, I had a really great editor who [insisted] these are all great little stories, but we need to shape it into a story. And she kept pushing that. And I think she was right in the end.

You’d think that they would keep a lot of information about themselves since they’re so good at keeping all of our other stories and often they hold the whole community’s history. But we found some stuff in some surprising places, like an old photo album of a library back in the 1920s under a kitchen sink. One of the things we learned along the way is that librarians are not necessarily the best tooters of their own horns,. You don’t go into librarianship to be a star or be in front of the camera. They tend to be more humble and helpful people, people who want to help you find your own information, so we got to tell their story.

Were there specific libraries you wanted to visit in your travels?

There’s almost 17,000 of them, so It’s like, where do you start? Originally, we wanted to tell the story of one big main urban library that was a big melting pot of people from all different walks of life, so we filmed a lot in San Francisco and in Queens and in Chicago. Then gradually we started realizing, “Okay, those are fascinating places. They’re super busy with all kinds of things happening, but it’s these smaller, quieter libraries that are under the media radar that are often the last public places in a small community where people come together that are facing the biggest challenges right now, whether it’s budgetary or political divides or book challenges. that’s really where the heart of the story lies to me.

It seemed like you really were able to dig in at the small-town library in Wisconsin. How did you end up stopping there?

Wisconsin is where all of my mom’s side of the family has been for many generations and it’s actually where I was born, so I have a lot of memories of little Wisconsin libraries when I was growing up, visiting them all the time. But the main reason we decided to really hone in on Wisconsin is that it’s a very politically divided state. There’s a lot of political tension and conflict there and it’s also one of the fastest growing homeschooling states. We were surprised to learn that these small town libraries are hotbeds of homeschooling activity, so there’s this Mayberry thing going on at the same time as a lot of political tension that intrigued me as a filmmaker.

If I’d been better at keeping a rein on my own tendency to go off and explore this new shiny thing, we would have finished the film about six years ago. [laughs] So we definitely fell into that pit of “Oh wait, things are changing so much and so fast.” But I’m glad we did actually. I think it made it a stronger film and a more timely film. But I’m also really, really glad at some point we were like, stop. Okay, there’s still all kinds of developments happening in this story, but now is really the time to get it out there in the world.

Was there anything that really changed your ideas of what this was?

It was mainly just stumbling across all these fascinating women and little glimpses of their lives in the archives. When we found Annie McPheeters and her oral history, and I just love her accent in the story that she has to tell, so it was like “Let’s fold that in.” It almost like the joy of discovery when you’re in the library. Our film company is called Serendipity Films, and we had a lot of serendipitous moments along the way with this.

You really do feel it. When you’ve been carrying this with you for some time, what’s the process like of letting it go and putting it out into the world?

We’re not letting it go yet. As one of my early film teachers told me, there’s the getting pregnant, there’s the having the baby, and then there’s the raising the baby, so we’re in the raising the baby stage right now. And what’s really great is how many libraries are responding. We have our broadcast coming up on the 29th, but before that, we’re screening in almost 400 libraries all around the country, a lot of them really small libraries in small towns, which is exactly that community that we wanted to hit and try and spark some conversations about what’s happening in their libraries right now. So I’ve been enjoying it. I like being on the road and I love going to libraries. And now I’ve got a new reason to go.

“Free For All: The Public Library” airs on Independent Lens on PBS on April 29th. It will be available thereafter to stream via PBS.