“Sometimes it’s hard to get excited to draw something a million times, especially a redrawing of something you did three times before,” says Dash Shaw, the celebrated comic book artist who was still basking in the warm reception he received at the Toronto Film Festival after the premiere of his animated feature debut “My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea.” “But if you’re playing at the Ryerson to a thousand people, you want to try to make it as awesome as you can.”

Though the adjective might be overused these days, “awesome” seems like one of the only words that could actually do justice to what Shaw and a small team of animators have accomplished with the comedy that at once feels as if every frame has been handcrafted while it continually opens up the mind with the ever-expanding world it creates, bursting with splashes of color in its artwork and its ideas as a dogged journalist for the Tides High Gazette named Dash (voiced by Jason Schwartzman) and his pal Assaf (voiced by Reggie Watts) uncover sketchy plans for a new auditorium addition that have destabilized the school, which sits upon a hill. Dash aims to reveal such plans as the school starts to be flooded, but to do so he must scale the equally precarious hierarchy that exists within Tides High, with freshmen, sophomore, juniors and seniors each fiercely protective of their own individual level, making it difficult for him and an increasingly motley group of characters who join him, including his editor Verti (Maya Rudolph) and the school’s lunch lady Lorraine (Susan Sarandon), to get to the top.

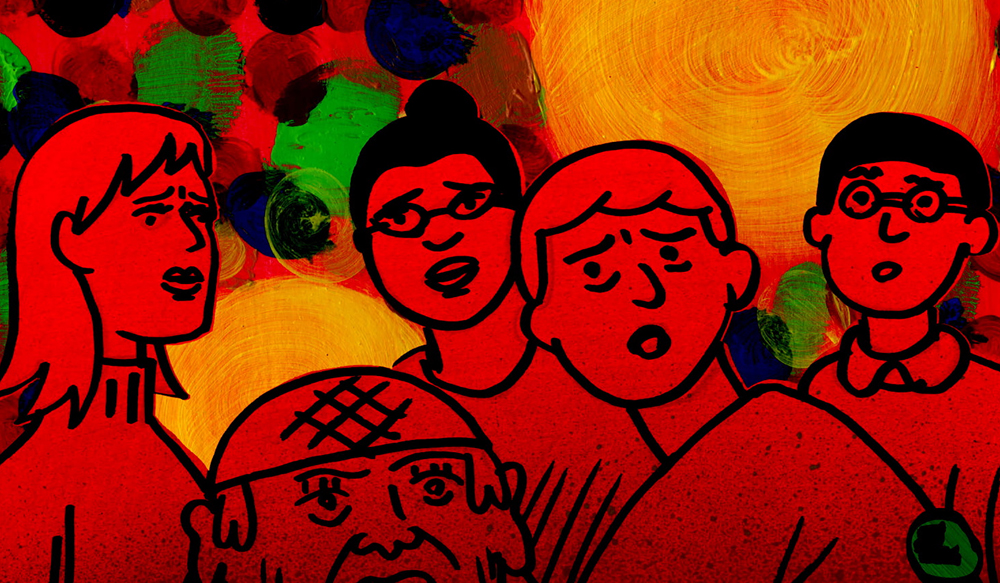

Nods to side-scrolling video games and juvenile non-sequiturs bring a tactile authenticity to the proceedings, but “My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea” finds a transcendent way into the emotional turbulence of that particular age, with Shaw’s evocatively trespassing the formal divide of the foreground in which his characters exist as line drawings often waiting to be filled in and the background where the bold red, blues and golds of the environment impress themselves upon the characters, signifying the continual shifting of moods and influences, some of which are likely to stick well after the they graduate, if of course they don’t sink first, either to their literal death in the ocean or simply by blending in so much where they no longer stand out as individuals. As Shaw brings in other artists to animate flashbacks, the film uncannily replicates the occasionally beautiful, occasionally frustrating and altogether surreal experience of the formative teenage years, finding the humor in the absurdities and indignities of daily life that are only more amplified without the wisdom to properly handle them.

In the midst of a barnstorming fall festival run that’s included Toronto, Fantastic Fest in Austin and sets up this week at the New York Film Festival, Shaw spoke about realizing his own ability to make a full-length feature after experimenting with animation for shorts and music videos, the unexpected influence of video game logic, and how music help make the movie.

The story was [from] a short comic story I had done in 2009 and for some reason, my mind kept going back to it because the initial impetus was to combine the two main modes of comics when I was a teenager in the ‘90s – the autobiographical, alternative comics on one end and the mainstream boys’ adventure stories, [which] were opposing schools at that time, but I really liked both of them. This little short story had the seed of mashing them together in a funny way where there would be a character who’s named Dash and it would be based on real experiences, but it’d be warped or stylized into an emotional realm. I felt that lent itself to animation because it felt in between Hollywood cinema [as a high school-set film] and the DIY, experimental cinema I enjoy if myself and this small team of alternative cartoonists that I know did it, so I found that this really goofy premise could carry all of these different things I wanted to do.

I was trying for many years to make a movie in a more traditional way where I would get financing and actors attached at the beginning and I went to the Sundance Labs with that project. I really learned everything I know about film from the Sundance Labs, but it never came together – that’s how it goes, and I wouldn’t trust it if the first thing I was trying to make immediately worked out [since] I believe you have to fail before you decide to keep going on anything. So I kept thinking why can’t I just be drawing this movie? I have the tools here and as soon as I saw that you could make GIFs in Photoshop – taking preexisting drawings and line them up and have them play at six or 12 frames per second – my mind went to “oh, you could make a movie” because the technology I saw that I could make animations with basically the same tools as I make my comics.

A scanner can function like a camera and these programs like After Effects and Photoshop can line up the drawings – I guess I knew that was possible before, but whenever I saw something computer animated, my mind went to Flash and these other kinds of computer-y looking cartoons. When I saw I could make traditional animations just using the computer how Disney used a multi-plane camera, I was very, very excited. The goal was to immediately take advantage of this technology to do something that uses old techniques, but in a new way.

Just the high school setting seems like such fertile territory because of how you can convey the crazy conflicting emotions of that time, which you in such a fascinating way with the way color is used throughout the film in the background. Did you know from the start how the background and foreground would interact with each other while often being completely different stylistically?

That very first comic was colored in a very strange way where the line art was literal and the colors were these almost Mark Rothko-like abstract shapes that were smashing into the line art, and I was trying to get at some kind of existential pain of being a teenager, so I thought those existential crisis painters of the new school of painting – Rothko, in particular – would be funny and strangely appropriate to smash into this story about these kids and the heightened drama of school. I also thought of it as a film score where there’s what’s happening in the scene literally, but it’s like a Bernard Herrmann score, so like there’s a woman driving and that’s what is happening [visually], but there’s this huge abstract strange element colliding into it – it’s not subtle at all. It’s really dramatic, so I was trying to run with that in the way I color comics.

I did that for a book called “New School” in particular where the [background] coloring would be photos that would align with the line art in strange ways, so the background/foreground collision was there and it was extremely exciting, and [in general] the movie came from interpreting things that I liked in my comics. I wouldn’t say they were experiments, but it was honing in on some language. Not to compare myself to him, because I think he’s the absolute greatest, but when [Osamu] Tezuka did the first “Astro Boy” series, it was rad how he used all of these things that he knew about composition, lighting and character design from his comics and applied it to animation. It makes the first season of “Astro Boy,” where the compositions are really bold, as cinema really hold up. They’re on par with Saul Bass. Like the very first episode of “Johnny Quest” is great because Johnny Quest was drawn in a semi-realistic style, and they would have to animate it, so they couldn’t really simplify it and they would attempt to transpose these noirish drawings onto this other world and what resulted looks fantastic. I think very highly of the world of limited animation that is made by comic book artists, particularly Japanese comic book artists.

You’ve got these great flashback scenes that are done by different animators – was that as much a stylistic decision as a practical consideration to finish the film?

It was both. I knew Jane Samborski, who’s the lead animator on the movie, would be hugely involved, but I also thought of all these people from alternative comics that I could cast in specific parts. There’s a million ways to make animated movies, but there’s the school of thought where one person creates the look of the movie and then tries to hire a bunch of people to draw like them, but then there’s what Ralph Bakshi really discovered [which] was casting artists like actors where he knew Mike Ploog would draw in a certain way, so let’s have Mike Ploog do this flashback sequence in “Wizards” and it’ll look awesome. [For this film,] Frank Santoro is a great landscape painter, so I thought it would be awesome to watch an animated movie and have his ocean waves in there. I hadn’t seen that before. So it made sense to treat these artists with respect and, knowing what they can do, incorporate them in a way so part of the movie’s style is the juxtaposition of all these things. That is going to happen in any collaborative process anyway, so I feel like it’s stronger to embrace those juxtapositions.

Since this was based on a short comic, did you have things in mind you wanted to expand on?

Well, the original short story was really nothing – it was just a “Titanic” parody. So there were multiple key components as I thought about it more – one was remembering working on a school newspaper and the friendships around the paper and being obsessed with books and writing. Now that the movie’s just come outn I see that people are responding to it as a “Freaks and Geeks” kind of mode or “these people are nerds,” but honestly these were just the kinds of people I knew. It would never occur to me to have a different kind of school experience than these kids, so then it became this entire movie is this kid’s fantasy of it.

Then another piece [of the inspiration] was each floor being a different grade. It sounds a bit silly that that was important, but it gave the whole thing a video game structure [where] could construct different dramatic scenes based on real things. I knew we could have a cafeteria scene in the middle of the movie, like the middle of a school day and the students divide themselves just like they do [at lunch] in real life or these kids have a friend that joins them for a little bit, but she goes to this senior floor before them and that’s like when you have a friend who finds an older cooler person to hang out with for a little bit and you get scared they’re going to leave you. And the video game structure felt appropriate, both relating to school, which is this ridiculous system, and also movies, which typically have a ridiculous amping up of drama.

Yeah, I never played a lot of games as a kid, but my friends would invite me over to their house to watch them play video games and it was very important to them that I see them get to this Metroid level, so I think it was just burned in my brain as a cinematic experience more than an actual participatory experience. Especially the earlier games, which have something that’s very much like limited animation in how the characters moved and how the space was handled. Every time a character moves from one room to another in my movie, it’s this shot of zooming through a door while the door opens that comes from “Resident Evil.” It’s very hard to draw someone like getting larger and moving through into a different room and explaining that, so that [ action in] “Resident Evil” really stuck in my mind as a way to handle that transition in a way that would be elegant and has an experimental film quality to it [since it would be] unusual to steal from that game and put into a movie.

Did you actually record all the voice work after the animation was done or were the processes intertwined?

I want to say 70 or 80% of it drawn before the actors came on, but then once we had their voices, we re-drew a bunch of stuff. If Maya Rudolph comes up with a really amazing thing to say, you have to use it, and it would be foolish not to draw something and put it in, so it was pretty organic.

In general, is this more or less what you thought it would be when you started out or is it different?

The whole thing was exploratory at the beginning, so if I compare the storyboards to the end movie, the seeds are all there of those characters and the graphic style. But I learned so much. There were so many things I hadn’t done before in animation that each one of those was a different head trip. I remember when it really felt like the mission was just to have something drawn, where we were replacing storyboards, and then it was like, “Oh wow, I can’t believe we drew a movie.” That was two years ago and that becomes, “Well, we should change this, that and the other thing.” Then I had never worked with a real sound designer before and I had no idea what the score would be at the very beginning. When the score came in, Rani Sharone, the composer, really clarified the tone of the movie, like this is carnivalesque and fun, but it also has a danger in it. I didn’t have a temp score and when Rani wasn’t there, the tone was way more all over the place [to the point] where we were like, “I don’t know what we have here.”

What’s it been like to send it out into the world?

I wondered a lot before what it would be like because I’ve never had a movie come out. I’ve never premiered at a film festival before and with it happening, I still wonder what I should be feeling, but it’s super cool. I really want to make another one and do it again.

“My Entire High School Sinking Into the Sea” opens on April 14th in New York at the Metrograph and in Los Angeles at the Nuart.