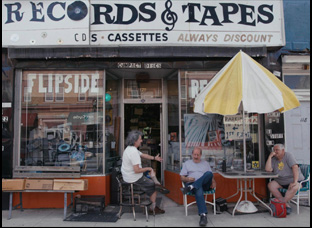

In documentaries, access is generally thought of as a matter of trust between a filmmaker and a subject, which could still hold true in the case of “Flipside,” but it was a matter of Chris Wilcha trusting himself with all the material he had collected over the years. Since turning the camera on himself in the late ‘90s for “The Target Shoots First,” in which he sought to expose the corporate culture draining artistry out of the music industry by taking a job at Columbia House, only to believe he’d been consumed by it whole, Wilcha had intended to make a number of other films where he’d be tucked safely behind the camera – a profile of the jazz photographer Herman Leonard, a travelogue following Ira Glass after the two had worked together on the TV version of “This American Life,” and the most personal, a tribute to Flipside, the record store where he worked as a teen in New Jersey and would tell the story of its owner Dan Dondiego, who kept it afloat even as the popularity of vinyl waned, and its colorful clientele like local legend Uncle Floyd, a vaudeville-style comedian who was ubiquitous on regional daytime TV.

What Wilcha couldn’t have known as he abandoned all those projects, overtaken by the need to put food on the table as a constantly working commercial director, was that he was gradually building up to tell a story that perhaps only he could tell, though so many have lived it themselves when combing over the material to understand why exactly he couldn’t bring himself to finish them. The result is an extraordinary achievement, if for no other reason than Wilcha can now say he has a second feature film in the can, but moreover, it’s rare to see any artist so openly grapple with why a career in the arts plays out how it does, balancing professional and personal pursuits, shifting cultural headwinds and simply the energy it takes to see any given project through. Wilcha has the good humor to see perceived disappointments in a lighthearted way, but he doesn’t skimp on the deep tissue work of examining what led him to let certain things fizzle while starting more work, steadily accumulating hard drives filled with odds and ends that would never come together — except it does with a perspective beyond any one individual project.

Delightful and heartrending in equal turns, “Flipside” may be a breezy watch, but one with all the richness of a film in the works for over two decades and after premiering at last year’s Toronto Film Festival to much fanfare, it is starting its theatrical run this week and recently, Wilcha spoke about inadvertently making the film of his life, the additional personal investments he made to complete it and what it was like to return to moments in his life using a more interrogative lens.

Yeah, there was definitely a moment where I thought, “Wow, imagine if it was like four or five half hours and you’d have like a David Milch half-hour and you’d have a Herman Leonard half-hour” and basically you treat it as a collection of case study documentaries. Then at one point, someone said, “You should do it as a podcast, sell the IP and then try to make it as a fictionalized feature film.” It was so convoluted, and it was a really hard film to describe on paper, so at a certain point, I was just like, “You know what? if I don’t just make this damn thing it’s never going to get done. So that’s when it became a standalone documentary and I actually think it’s probably exactly the length it needs to be. You don’t need five half-hours. Ultimately the documentaries within the documentary all ended up finding their best length.

Was the record store always at the center of it?

I started shooting at the record store out of pure love for it. I just loved being there. I loved making images of it. I loved talking to all of the crazy characters who passed through the place, and Dan the owner. But there came a point where I would return there every year and spend some time shooting and I realized that there wasn’t a feature length documentary to be made about the store. Maybe it could have supported a short film, but that material of returning home and to this fountain of youth from my past inspired starting to sift through all these old hard drives and seeing all the projects that never came to pass and languishing either on Hi8 tapes or MiniDV tapes and the record store provided that anchor. That’s like the time travel machine that you go in and out of and come back to, to then spin out and tell these other stories.

I think it did confirm something for me personally, which was I have this instinct to document stuff, which is a compulsion I think a lot of people have, but I often have this moment almost like a street photographer who goes out and takes pictures where I want to start documenting this and I’m not even thinking about how it will get funded or what the end product is, but something in front of me demands it. I’m worried that it’s going to disappear or it’s never going to happen again or that it’s so special and unique that it should be documented. So when I started to look back and assemble all of these disparate things, I actually felt like I should have more faith in that instinct because most of those impulses were good — the impulse to go and shoot with Herman Leonard, the impulse to try to document Uncle Floyd and where he’s at in his life, even to revisit David Milch, [which] felt like a very meaningful thing to shoot with him at this particular moment in his life. It affirmed that I should listen to that inner documentarian that says, “Go out and shoot the thing.”

Did you know you had to be at the center of this? After “The Target Shoots First,” I imagine you might’ve been more comfortable in that position, but maybe not at first?

I will fully admit that I wrestled with it. I started to assemble it and I just got a little cringy and uncomfortable because nobody wants to hear the midlife musings of this dude, right? I still felt I needed to narrate it, but I really pulled back and wasn’t in it nearly as much. Then we started to do some screenings for friends and family. Basically they [said] “You have to put yourself in it more. We’re feeling the coyness of you, not being fully vulnerable and present in the footage.” So at a certain point I gave over to this and started to kind of incorporate some more observations about family and the experiences I was having midlife and the stuff started to echo a little bit more with the footage that we had assembled of the other characters. It was a real balancing act and there are days where I feel like I got it right and then there’s days where I’m like, “Ah crap, should I have included this or that?” I definitely struggled with it.

I was very worried because once this became legitimate and it started to cohere into a film the people I was working with said, “You have to go back to all of these people and get releases and even if you got a release back then you have to go back and get a release now because there’s no way some ancient scrawl on a napkin I asked for at the time would hold up.” So I was very worried that Ira Glass might say to me, “I don’t actually want to be a part of this” or Herman Leonard’s estate might say, “Thanks but no thanks.” But after a lot of really delicate conversations and love letters to people and sending links [of cuts of the film] and waiting anxiously for responses, everyone pretty much said that they were pleased to be a part of it. They gave me permission to finish, so it was really tricky and a very weird part of the process where I was like, “Oh damn, these people thought I shot this thing ten years ago and not even thinking about this [now] and here I am as a voice from the past saying, ‘Hey I want to use that footage again.'”

In this funny way, I think Ira had almost had forgotten about that experience or it had just really receded in his memory and he’s been really supportive. He’s coming out and doing some Q&A’s in for our New York screenings and Herman’s daughter has been so generous — I think she likes the idea that maybe a different generation of people might be exposed to his photographs again. We know that the audience for this is modest, but even just to get the word out there about him and his photography, making sure that his archive doesn’t disappear has been really meaningful. I also had a really lovely conversation with David Milch’s wife, which was really meaningful for me and I hope for her about this funny experience that I had that seemed to resonate with her as a familiar tale.

When you’re putting all of this together from the past and present, was there a moment you knew it worked as a story?

One breakthrough for me was when my editor Joe Beshenkovsky started to experiment with the recurring voices — the idea that you see a profile or portrait of a character and then they go away for a while, but then all of a sudden they recur and eight or 10 minutes later this voice pops up and it’s kind of disembodied and they’re no longer talking about their story but they become a voice hovering over the documentary, like a philosophical overview or a guru that’s weighing in on the other themes or topics that are related. Once we started trying that and it started to work, that was a big moment. We realized that we could break certain character profiles into different pieces, so you didn’t just sit with one single Uncle Floyd section. There’s a couple of different times that Uncle Floyd appears in the film, for example.

Something really interesting happened that had to do with technology, which is I would often record my voiceover in completely informal circumstances, literally sitting in my car or in this a little office space or on my kitchen table because Joe the editor constantly needed refreshed voiceover. My co-writer Adam Goldman and I kept revising and changing and tweaking the writing so every day I’d have new voiceover to send him and by doing that it just became a thing I had to do and I wasn’t self-conscious about it. We had a date on the calendar where I was supposed to re-record all of the voiceover and I was actually a little freaked out [because] I [thought] “What if that day the performance of it isn’t good or I sound tighter all of a sudden? I’m in a studio and we have the meters running and it’s expensive.” But our editor and our sound mixer did a pass at the voiceover where they managed to completely unify all of these totally disparate takes that came from different time periods and recording circumstances and the mixing was such that all of some of that casualness or off-guardedness or unselfconsciousness was able to be preserved. So it didn’t turn into “I’m in a VO booth with a $20,000 microphone, totally freaked out about just rushing through this.” But we actually got to use that VO from [over the course of] the year we did it.

It’s part of what makes this film so personal and inviting. What’s it like to finally have something to share with audiences after all this time?

What has been an amazing breakthrough for me is just having finished it. We joked that when my name comes up as the last credit right after the last line, it’s part of the plot of the film [because] these things that I’ve been carrying over this long period of time and the sustaining belief that they were maybe worth keeping or preserving or assembling into something has provided an immense sense of relief that it was worth doing. Now, I want to do it again right away. I don’t want to wait another decade to make another film. That’s been a really lovely consequence is simply just the feeling of completing it and not carrying around these half-baked ideas anymore.

“Flipside” opens on May 31st in New York at the IFC Center, June 7th at the Monica Film Center, the Laemmle NoHo 7 and the Laemmle Glendale, and in Seattle at the Grand Illusion Cinema before expanding. A full list of theaters and dates is here.