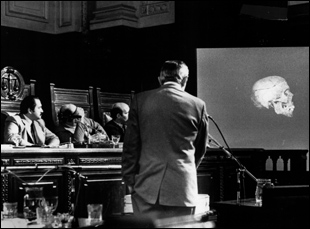

If the military dictatorship that presided over Argentina from 1976 through 1983 had wished to bury their history, quite literally leaving the thousands that were seen as political enemies in unmarked graves across the country during what became known as “the Dirty War,” they didn’t count on the arrival of Dr. Clyde Snow, a forensic anthropologist brought in by the government that succeeded the previous one to conduct a full review. Dr. Snow, an American who had been used to exhuming remains to piece together cases against serial killers such as John Wayne Gacy encountered a workload unlike any he could even fathom in traveling to South America, not only faced with an unthinkable amount of bodies to identify, but the additional challenge of being able to recruit assistants when the threat remained of the military coming back into power as a fragile democratically-elected government was attempting to seek justice for the families who lost loved ones.

When it would be difficult to put a face on those that would become known as “The Disappeared,” director Bernardo Ruiz manages nonetheless to find a compelling, all-encompassing human story amidst the most inhumane of circumstances in “El Equipo,” chronicling Dr. Snow’s efforts to build a team of anthropologists who could help with uncovering evidence of the atrocity when experienced professionals were hard to come by. With the help of his interpreter Morris Tidball-Binz, Dr. Snow looked towards college campuses to find volunteers in archeology courses who could learn on the job, an undertaking that would require both patience when kitchen utensils and window screens were all that could be afforded in the early days and great emotional detachment when they were unearthing fellow Argentineans of their age and younger. Still, for then-students Mercedes “Mimi” Doretti, Luis Fondebrider and Patricia Bernardi, the personal toll it could take took a backseat to how their work could ensure that this history is preserved so as never to be repeated.

“El Equipo” is powerful in achieving the same goal while tracking how Dr. Snow’s team would eventually grew into a more formal organization — the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF) — that unfortunately hasn’t had to lack for work in the years since completing their search for bodies in Argentina, responding to war zones around the world from Haiti to Bolivia where they aim to give families the peace of mind of knowing what happened to their relatives. Beyond profiling some remarkable characters led by Dr. Snow, a cigar-chomping Texan who died shortly after Ruiz began the project nearly a decade ago, the director is able to convey how the past is very much alive, not only in the minds of those who spend their days conducting archaeological digs but in how it continues to shape the future. With the film recently premiering at the Santa Barbara Film Festival en route to a bow at Big Sky Film Festival in Missoula, Montana later next week, he spoke via e-mail about how challenging it was for himself to piece together a history of the EAAF given their scrappy start and the specious historical record during this time in Argentina, the gift of getting to know Dr. Snow before he passed and letting go of a story that still is very much ongoing.

What got you interested in this?

What got you interested in this?

In the mid-2000s, I met a young forensic anthropologist who told me about Mercedes Doretti and the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF). A story about Latin American forensic anthropologists working on behalf of families of the disappeared felt like it could be a fresh way into the true crime genre – and also a way to get at some very important political history through the story of one scientific team.

After completing my first feature documentary “Reportero” in 2012, I contacted Mercedes Doretti and expressed my desire to make a film about her team [and[ she suggested an opportunity, which in retrospect was clearly a test of my resolve. She said that if I were serious about making a film about the team’s history, I should immediately interview Dr. Clyde Snow, who was then 84, so in January 2013, I traveled to Oklahoma and filmed Dr. Snow in his home, conducting an extensive on-camera interview with him. I believe that is the last known recorded interview with him, and it was the beginning of a decade of work.

What was it like to film with Clyde?

What you see in the film is what I experienced with Clyde Snow. He was eccentric, funny and able to size people and situations up very quickly. Newspapers, magazines and television shows loved him because he was such an interesting character — and part of why we have so much good archival material about him. But once he captured media attention, he knew how to reframe issues. As an example, regarding Guatemala, he told the Washington Post in the early ’90s, “It’s too bad Jeffrey Dahmer didn’t come to Guatemala because he’d be a general by now.”

Snow understood that media outlets tended, then as now, to lavish coverage on “lone wolf” serial killers. He was very savvy at keeping media attention focused on human rights issues that would otherwise be ignored by big outlets. And when you learn that Snow chose to have his ashes buried in places where the disappeared are memorialized in Guatemala, Argentina and Iraqi Kurdistan, you know exactly what his life’s work was about.

Was this actually the most archival-heavy story you’ve done? As someone who generally does verite, was it different to approach a story in this way?

It’s true. This is the most ambitious archival project I have undertaken as a director. Producer Gabriela Alcalde and editor Fabian Caballero did outstanding archival work for this film and deserve most of the credit. We were also lucky to work with excellent researchers in Mexico and Argentina. One aspect that is fascinating about working with archival material is that you can clearly see how every point in history has its own storytelling conventions — and it makes you think about how contemporary events will be documented and remembered.

The work of this particular project was about assembling fragments, working with pieces of media, so there was an aspect of it that was like solving a mystery [as the scientists are doing]. In a very modest way — and in no way on the same level as the work of the EAAF scientists — our team had to create order and meaning out of fragments and editor Fabian Caballero was particularly adept at creating scenes from the pieces we had collected over the years.

I was taken with the story of Lilyana, a young expectant mother who was abducted by a death squad, leaving her mother to wonder what happened to both her and the baby. When there must be so many individual stories like that and yet so many unknown as well of the disappeared, was it difficult to decide how much of those stories you wanted to tell without taking focus away from the team?

There is obviously a version of this film that is focused on the testimony or experiences of family members of the disappeared. What I ultimately found the most compelling for this specific project, was the relationship between Clyde Snow, who would have been about 56 when he first traveled to Argentina, and this group of Argentine students, some of whom were as young as 19 and the way that relationship evolved over time is fascinating, a real world story as moving and dramatic as anything a fiction writer could come up with.

Were there unexpected directions this took that changed how you thought about it?

I don’t want to overstate this, but when I began the film, there was maybe less of a sense of urgency in the U.S. around stories that have to do with unchecked authoritarianism and the consequences of powerful governments dehumanizing the opposition. Obviously the events in the film are specific histories, but I have noticed that the themes and ideas in the film resonate with people in the U.S. in a way that feels more urgent than when I started a decade ago.

With all that time put into it, what’s it like to start getting it out into the world?

I think it is increasingly hard to make films like this, given the current market pressures to make explicitly commercial or celebrity-driven films. I don’t say this in a self-righteous way because I have a foot solidly planted in the commercial TV/streaming universe. But one thing I have learned from past experience is that these smaller films have a way of sneaking through the cracks, and generating unexpected impact. Screening PBS’s Independent Lens at the end of year will help us reach a broad audience in the U.S.

“El Equipo” will screen next at the Big Sky Film Festival on February 20th at 7:45 pm at the Missoula Community Theater in Montana and will be available to stream virtually throughout the U.S. from February 20th-25th.