A few weeks before Zeshawn Ali was close to locking picture on “Two Gods” after filming for close to five years, he received a call in which he learned that one of his subjects had lost a loved one. He didn’t think twice about going back out to film for as long as it would take to capture the gravity of the situation.

“This film was never about us making a film that we needed to lock and release into the world,” says Ali. “It was like how to we reflect the journey as holistically as possible. How do we encapsulate all the details and changes in life and perspective that our subjects had and our editor wasn’t always thrilled because I’d call and be like, “You’ll never guess what happened. I’m going to be filming for the next month” – and the act three of this film got delayed a whole year because of many changing circumstances – but it was worth it because we captured the full breadth of this chapter of their lives.”

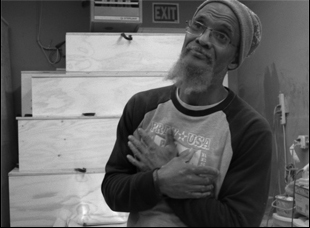

As it would happen, death loomed large over the making of “Two Gods,” but accepting it as a part of life was something that Ali and his brother Aman, who produced the film, picked up from their central subject Hanif, a casket maker in Newark, New Jersey where tomorrow is hardly promised in a city where more Black men are killed than anywhere else in America. While that statistic is sobering, there is a relative calm around Hanif, who has found a steady living in a place where many turn to crime to make ends meet, as he once did, and has found purpose in his Muslim faith, helping those who have died safe passage with a proper burial as well as those young men in his community just at the start of their lives who can look to him for stability and guidance. While his relationship with his own son is strained when he couldn’t be there for him while serving time, Hanif has become a better man to serve as a father figure to the 12-year-old Furquan and the teenager Naz, both of whom have strong women in their lives, but no other men around to look up to.

While Ali’s stark black-and-white cinematography is stunning, “Two Gods” allows one to settle in and simply lets life take its course, celebrating the moments when its subjects can feel content with their circumstances, but observing how much is out of their control, leaving systemic issues abstract but present throughout and rather than insisting how hard life is, it honors the fortitude to keep going. After premiering virtually last year at Hot Docs, the film is now available to all at virtual cinemas, supporting your local arthouse, and every virtual screening is accompanied by a conversation the Ali brothers had with Vice co-founder Suroosh Alvi. Still, the Alis were kind enough to talk about how they made such a beautiful film, letting go of any of their own ideas as the story started to take shape and how they hope the film makes it easier for people to have the typically difficult conversations about planning for the end of life.

Zeshawn Ali: Aman and I were already in the process of telling stories [with] nuanced portrayals of Muslim-Americans. Aman had done a really great series called “30 Mosques in 30 Days” where he was telling Muslim stories during the month of Ramadan, and I came onboard for the tail end of that project to help out a little bit, and we were like, “There’s got to be more out there.” We had our ear to the ground and that’s where we got introduced to the casket shop in Newark.

Aman Ali: We just had a fascination about the business of casket shops and the Islamic burial process. We are Muslim, but very often you don’t really know about these traditions until they happen, so there was definitely a tremendous amount of curiosity, just learning about how this all works, but Hanif is such a refreshingly vulnerable, tender loving person and [someone] we just wanted to spend hours and hours and hours and days and days and days with. So as soon as we met him, lightbulbs just go off. Like this is a guy that I want to spend an hour-and-a-half with in a theater and learn more about.

You find a far more sprawling story here – was it easy to keep track of with a small crew?

Zeshawn Ali: It was a really organic unfolding of events. The entry point to this world was definitely the casket shop and then Hanif and the openness that he had and through that close relationship that we formed with him, we met Furquan and then we met Naz, and the film takes all of these detours in our subjects’ lives, all of these things you could never plan for, and it was hard because at the time they were extremely difficult situations in their lives. You had to care about the well-being of these people that you grew to care so much about, so really navigating that unexpectedness was challenging, but when we were editing the film, it was like we needed to keep all of those detours there, even if it didn’t feel narratively perfect or linear in any sort of way. Life throws you those curveballs and what the film hopefully shows is there’s a reckoning with the [unpredictability] of life that really teaches you about what our journeys mean. That was the mentorship lens that Hanif always had — his life was a series of detours, some of them really challenging and some of them really beautiful and meaningful, and we wanted to hold both of those with equal weight — so once we grew so close with our subjects, we were following them every step of the way.

When it’s your first feature, was it a different experience feeling things out and finding the sensitivity points when you’re spending as much time with your subjects as you do?

Zeshawn Ali: Yeah, there’s a level of comfort. The film was secondary in many ways. The camera was really a way to reflect back the closeness that our subjects had with each other, but also ways in which we were navigating these moments in shared spaces, so the sensitivity and vulnerability was there in what you see in the film. There were also days of time spent where there was no camera rolling because we were just there navigating these waters together and the ways in which the cameras were used was to capture the moments where our subjects were wanting to capture a very specific part of their lives. It was always this constant conversation of how we were going to show those challenges and moments of real honesty and vulnerability and that’s how we talked with each other. We talked about the good things, we talked about the really hard things, we talked about everything in between, so that vulnerable space was we had to hold it with as much care as possible, not only in the filming, but how we crafted that editorially.

Aman Ali: That care was supercritical because very often when it comes to communities of color, they’re very often talked about in terrible, very hurtful, racist ways and for us, especially in a city like Newark, New Jersey, there’s a lot of skepticism when anybody comes in the community with cameras. Our lens was there’s a reason why people live here and why people take genuine pride and joy in being a part of this community, so let’s see people the way they see themselves. Let’s strip away all preconceived notions and narratives that we may have and that speaks to the film we have [where] as filmmakers, you have direction and places where you want the story to go, but at the same time, you’ve got to be open. You can’t just have this preconceived story in your head and try to force something down a particular path. You have to see people the way they see themselves and be open to where the journey of their lives take them.

Zeshawn Ali: Yeah, I wanted the film to feel like as intimate as possible and the proximity that the camera has to our subjects was really just a reflection of that care. It was always framing people in the most soft, tender ways that we could because we are talking about really difficult things in the film sometimes and for instance, when you’re in a car with Furquan and there’s rain falling on the window and the camera is right in his face, you want to reach out and give that person a hug, so the camera is a reflection of the level of care that was existing in the environment all around us. Furquan and Naz were young protagonists, so we wanted to be at their eye level, see the world through their eyes, always making sure that our camera was meeting our subjects where they were.

There’s not that many wide shots in the film because we felt that we’d lose the intimacy in some ways. We wanted you to feel as close as possible to what was happening, so some of that was in the edit, and our editor Colin [Nusbaum] always jokes, “There’s not a lot of headroom in your film. Your film is just right up in the moment” and that’s because of how I filmed. I was right next to people when I was filming them. I never wanted to be far away from them. And we found more meaning in it as we reflected on it in the edit. It was really an important way to look at the footage and understand what type of story we were telling.

The sound design is really complementary when it’s bringing the community into the film without seeing them when you have the close focus on your subjects. What was that like to work on?

Zeshawn Ali: We had such an amazing team that were working on it and we wanted it to feel really textured and layered. This film is so much about the physical relationship that people have with one another, the rituals of death and the casket shop – there’s such strong visual language, but all those visual languages have such strong sounds associated with them, so the sound of a sanding down a casket, the sound of people breaking their fasts at a mosque, the call to prayer echoing through the streets, it’s all these sounds were details that were inherently part of every day lived experiences of our subjects, so we really wanted to layer that.

The score was a layer as well that we wanted it to feel as richly textured and intimate and reflective of the spaces that the camera was being present in and our composer Michael Beharie did a really incredible job making a score that felt like sound design. It’s not always a melodic score. It’s a score that reflects the movement of water and reflects the call to prayer and the textural sounds of wood in a casket shop.

Was there anything that happened that changed your ideas of what this could be?

Aman Ali: There’s so many things. We realized the impact a story like this could have and just from our own experiences in filming, how grossly underprepared people are when people talk about death. We saw this film not only as a film we were getting out into the world, but as an opportunity for people in their own homes and in their own lives to start having these conversations. Very often, we don’t talk about death until these things happen and we want to use this film as a tool. For example, we’re partnering with a lot of organizations around the U.S. not only doing screenings, but [doing] what we’re calling life planning workshops and death preparation workshops where we want to normalize conversations about putting together a will, talking about end of life care decisions and health care directives with your family because when these things happen — and they will happen to everybody — we want to have these conversations now so when they happen, we can comfortably grieve. Initially, we didn’t think about those things or realize how much people need a story like this, especially during these times. We couldn’t have anticipated the pandemic or how much this film resonates with people because we all have these experiences in our lives, but it pulls upon so many threads.

Zeshawn Ali: And the turning point for us when we were making the film was it became very quiet and reflective as we continued understanding this tangible beauty of these rituals. On a personal level in the middle of editing this film, our father passed away and we had to do these rituals in our own life and that radically changed the film that we were making. In addition to the changes in our subjects’ lives — [when] we were going to North Carolina and filming with Furquan and Hanif was not building at the casket shop for a period of time because of difficulties in his life — we were navigating our own reckoning with loss and suddenly there was this inherent desire to just let everything stay still and be very reflective. That’s when the film takes on this tangible thread of quietness and holding grief in a way where it feels experienced, even if we don’t talk about it directly. The unplanned details of our own personal experiences really played into the film we ultimately walked away with, which was something that felt really intimate and reflective and quiet, holding joy and grief with equal weight. That was the tone we always really wanted to walk in the edit.

Aman Ali: We had an idea of where we wanted the film to go, but life happens and things just kept coming up. We weren’t really chasing a superficial [deadline], so we had a lot of flexibility because the story we were trying to tell wasn’t so linear, [though] obviously with budget and mechanics, we can’t film for years and years and years and years, but we were super open from the get-go of wanting to be a part of this journey with our subjects.

What’s it been like getting it out into the world?

Aman Ali: Obviously with COVID, it’s been a challenge, as with any film, but it’s been such a rewarding journey and just hearing people’s responses has been incredible because naturally with a film like this, it’s going to bring up so many different reactions based on your experiences. At first, people go into it not really knowing what to expect and then the takeaway is they’re really, really moved by it and we aren’t expecting people to feel a certain way. As open as we were with filmmaking, we wanted people to be as open as they can and reflect on their takeaways with the film.

“Two Gods” opens in virtual cinemas, supporting your local arthouse, on May 21st. A full list can be found here.