When Alla Kovgan moved to the United States from Russia, and while her background was in languages, she had a difficult time trying to articulate exactly what she wanted to in screenplays, a realization that drew her to dance where no words were needed. She would go on to become a founder of Kinodance, a multidisciplinary artist collaborative based in Boston and establish the St. Petersburg Dance Film Festival not long after where she was having a conversation with the filmmaker Charles Atlas, one of the longtime collaborators of Merce Cunningham, when the subject of making a film about the avant grade dance choreographer came up.

“I remember talking to [Charles] and I was like, ‘I can’t even imagine how you approached that work because with Merce, it’s like 16 people going in different directions,’” recalls Kovgan.

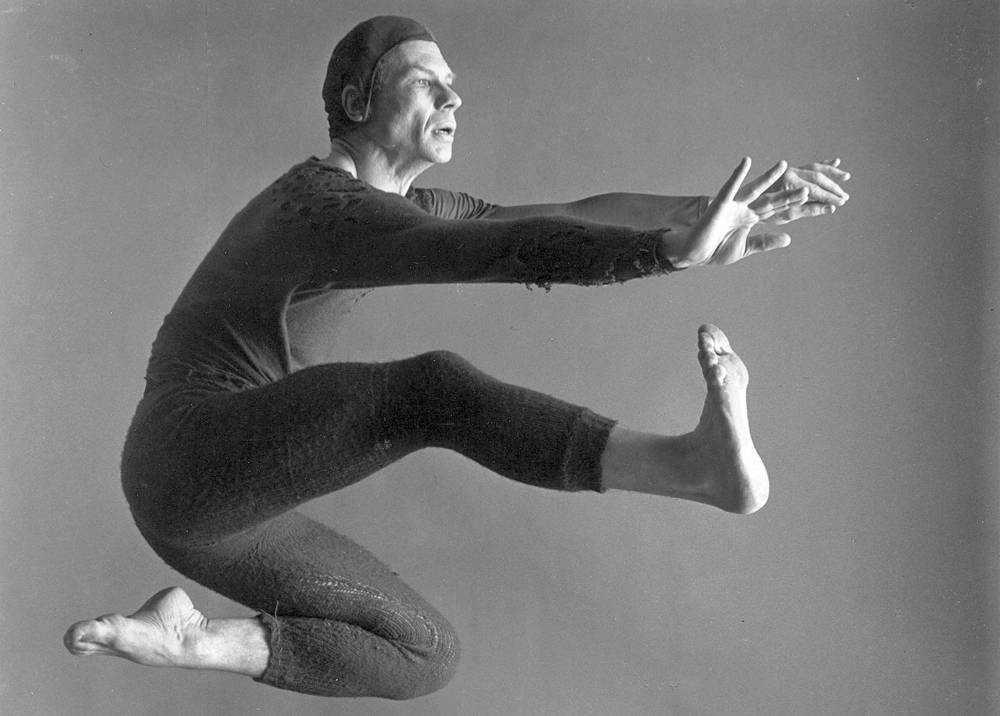

It was the turn of the century and Kovgan would spend much of the first decade of it establishing herself as a talented film editor in addition to continuing to work with dance, and while she had put aside that conversation with Atlas, it would snap back into her mind upon seeing one of the final live performances of Cunningham’s company, which he still danced with until his death in 2009 at the age of 90, and realized there might be an appropriate way to preserve his groundbreaking work for generations to come in all its complexities — despite insisting on a purity of the form that involved often only adding music after the fact, he employed the remarkable flexibility of the human body to explore fully all the ways its can be used to express the emotions inside.

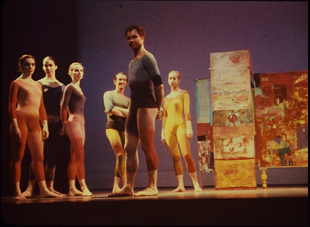

For an artist whose creative streak often cross-pollinated with others to birth an entirely new way of thinking about art – with the musician John Cage and the painter Robert Rauschenberg, he was one of the chief co-conspirators of the abstract expressionism movement – it was entirely fitting that Kovgan latched onto 3D, recently reinvented by the likes of James Cameron’s “Avatar” and Wim Wenders’ “Pina” at the time she began in earnest on “Cunningham” in 2011, to properly convey the layers of the choreographer’s work. The ability to better replicate the experience of seeing Cunningham’s events live is one benefit of working with the latest technology, but the filmmaker truly honors her subject with actual innovation of the form, using the depth of the frame to show the different ideas and influences that went into each dance sequence Cunningham created by occasionally superimposing different images on top of one another, exposing both the contradictions of a complicated artist and the genius of bringing disparate elements together in such a beautifully complementary way.

The result is something that truly makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand on end, perhaps even more so upon learning that Kovgan was working with just 18 days to film the extraordinary dance sequences that bring Cunningham’s work so vividly into the present, and shortly after the film made its premiere at the Toronto Film Festival, I spoke to the filmmaker about the seven years that went into getting those two-and-a-half weeks of filming go exactly right, what limitations were placed on her by having a subject who placed so few on himself and being able to resurrect “Changeling,” a dance piece thought to be lost entirely until it was recreated for the film.

I feel like it found me versus I found it. There was a commission from the Rockefeller Foundation’s Dance Films Association,to make a film about New York-based choreographer using 3D-based technology. I was working on another film, so I didn’t quite want to get into all this, but then I went to see the Cunningham Company’s last performances in 2011 and I’ve seen Cunningham before, but when I looked at it, I remember sitting there and feeling like, “My God, Merce in 3D could be really good.” Of course I had seen “Pina” and there was one “Rite of Spring” sequence in where I remember what 3D can do for dance. In 3D, I think our perception slows down neurologically, so we have more time. We can have longer shots. We can let people dance longer in a single shot. From there on, the company was closing and I thought, “Here are these 14 dancers who are going to be out of jobs next week and they’re the last generation trained by Merce himself,” so I felt incredibly sad these people who were still incredibly capable and in their prime as dancers, they’re just going to be gone. That was another big push for feeling this ephemerality of the moment, so that’s how it began.

And it feels as if it’s about a moment, rather than a life, though it illuminates so much about him. How did you figure out what this would cover?

Yeah, it’s not a biopic. It’s a film that tells a choreographer’s story through his work, so the work is first, and then all the archival [material] gives a sense of who he was. We’re actually following the chronology very carefully from ’42 to ’72, because it was very interesting to [see] the evolution of his ideas was because according to him as a human being, you are at your best when you’re actually moving and I wanted to keep that, and we only gave as many facts and as much information as was needed to keep you engaged. And many people remember Merce as an old guy. They say, “Oh he danced in his seventies and he took the stage when he was 90 and that’s true, but at his prime, there were very few people there when he was at his best, so I wanted to bring that back and I didn’t want people talking about Merce in the past tense. Now some of the interviews are from a later time, but they are really ruminating about what happened to them and it’s a time of struggle for them. They didn’t know if they were going to make it or not. It was constantly a state of uncertainty and that gives an energy and grit to this experience. There’s actually a lot at stake for them. You tell people now you work for 30 years without knowing what’s going to happen, they’re going to quit and become a physical therapist. [laughs]

Did the idea to use 3D as way of showing how experience can layer itself on top of one another come immediately?

Did the idea to use 3D as way of showing how experience can layer itself on top of one another come immediately?

For the 3D, the camera is sort of stupid. You have to tell it what to do. When you are watching the dancers onstage, you are the one who chooses where to look, but here we need to choose [where to focus] as filmmakers, so we have to choreograph the camera in connection with the dancing. Of course, Merce works in space, and it’s not like one person standing, going into some crazy state. It’s about the relationships between bodies and space and time, so 3D is perfect for that. I had two amazing people working with me – Jennifer Goggans, who is the director of choreography and Robert Swinston, who is the supervising director of choreography, and they’ve been with Merce for all these years, so it was a process of trying to make choices [for the dance sequences] and focus viewer’s eye.

But of course, everybody asks, “Why do you film this [particular dance] on the rooftop or why do you film this in the forest?” and we reviewed 80 dances between ’42 and ’72. Out of 80, we picked 22 and most of the iconic works were collaborations with Rauschenberg because it was a very important period where [he, Cunningham and Cage] were like a family, and from those works, we also picked excerpts. Behind each work, there was a physical question because Merce never worked from a narrative. He worked from a physicality, so he’s interested in action of falling, of being close together, of layering, but also in the action of Dostoyevsky, so he would ask those questions and then he would find a way to work with them. We would identify each question and then we tried to think of how to work with it within cinematic terms because we are in cinema with a big C.

We’re making a cinematic experience away from stage, and hopefully, we’ll get an idea of Merce, but it won’t be a replica of what’s happened on stage in any way. And once we picked the locations – I call them metaphorical locations because they came as a result of this analysis basically of trying to create a space that would help us translate Merce’s ideas into cinema, it was a constant process of refining and you storyboard to death. By the time you get to the shoot, everything is worked out a hundred percent and rehearsed.

You mentioned at the premiere that because the financing came from Germany, you had to shoot there. Did that become a blessing in disguise, having limitations as to where you could shoot?

No, I looked at 35 opera houses or something…

It’s still an entire country. [laughs]

It’s a huge country. If I were to choose, I would shoot this in New York City, just because it’s so important for Merce and we storyboarded everything in New York, but then there was no way to make it work. It’s interesting because when I began, everyone was thinking I’m nuts. How do you make a 3D movie about an avant garde choreographer Merce Cunningham? And with the Germans coming onboard so strongly, I incredibly appreciated it because without them, it never would’ve happened. But it wasn’t easy. We had to shoot in different provinces because of the funding, so we actually had to go to these places and it would be much easier if it was in one place, so we researched [various] locations. There were massive location scouts and many, many trips, trying to find a place that would basically resonate with what we were looking for.

I was intrigued with how you discovered the existence of “Changeling,” a dance thought to be lost, and you could interpret it anew, which made me wonder did you have to complete the archival portion before shooting the newer material?

I was intrigued with how you discovered the existence of “Changeling,” a dance thought to be lost, and you could interpret it anew, which made me wonder did you have to complete the archival portion before shooting the newer material?

When I decided to make a film about Merce Cunningham, I didn’t know what kind of film it’s going to be. I started researching and the period I got interested in was the early period about how Merce became Merce, about a young dancer who came to New York and then finding his [footing]. So I [went to] David Vaughan, the Cunningham historian who met Merce in 1950 to whom the film is dedicated, and David had index cards of every single performance or recording, and of course, the Merce Cunningham Trust gave us a license, so I immediately got access to a lot of the material that was known and available. But then I started realizing there was some material that nobody that got lost or nobody researched, and I was an editor for 15 years, so I know how to work with archive, and basically, I was like “We’ve got to look. We have information, we’re going to go through this archive and we’re going to make them find it and we’ll just push forever. When they say they don’t have it and we say, ‘Okay, keep looking.’”

That’s how “Changeling” was found. I couldn’t believe it myself when they said, “Yeah, there’s this ballet [with] credits that say “Merce Cunningham” and when we found that dance, it was a real tide-turning moment. All of a sudden, people saw this as not only a movie – and a 3D movie, which nobody could imagine, honestly — but [as something] that really contributes to the legacy of Merce. That dance was on that shelf for 50 years and nobody had seen it, but we realized it was the same dance in home movies, and actually it was something several years earlier that one of the husbands of one of the dancers showed in their studio, but nobody knows it was that dance, so I wanted to bring it together [through editing] how close actually it was. Then of course, we recreated it with the live dance because it was part of the world tour, so that was what film can do is it it can connect the dots over time.

In general, [Merce] was so lucky to work in this era of amazing American art, so there were all these avant grade filmmakers, and I come from a background of experimental film, so of course, [D.A.] Pennebaker and [Ricky] Leacock were all around, and I knew of Stan VanDerBeek, who did this “Variations V” with Merce, which is this multimedia performance in the ‘60s and I [knew] VanDerBeek must’ve shot him in his studio and sure enough, we were digging in the MoMA archive and here’s all this footage of Merce on 35mm. It was like a bottomless well and Merce always said yes to things. One of my favorite discoveries is Dick Fontaine’s film called “Sound??” that’s between John Cage and Rahsaan Kirk Roland, a jazz musician, and Dick Fontaine juxtaposed [the two] because he wanted to prove that not only white musicians were working with electronics, but African-Americans also, and these guys never met, but it’s a fantastic film we found in the Harvard Film Archive. Nobody knew where it was, and it became a journey on its own of unearthing those kind of gems that created another layer [for the film].

This may be a naive question, but since he choreographed without music, did it become tricky deciding what music you wanted to attach to it?

This may be a naive question, but since he choreographed without music, did it become tricky deciding what music you wanted to attach to it?

It’s a very complicated question. At first, when Merce and John got together, they’d agree on the length [of a piece]. They’d say, “Okay, this dance is two minutes. I’m making two minutes of music and maybe even there’s points [of coexistence].” Then it got completely separate. They didn’t even talk, but at the same time, “Second Hand,” lots of dancers were there [and said] it is choreographed to music. Originally, it was supposed to be choreographed to “Death of Socrates” by Satie, who Merce loved. And he loved a lot of other [musicians], so it’s not that he always avoided [music], but it was true, he believed movement had its own rhythm. In a sense, you don’t need music to cross the street. You cross the street by yourself. Nobody plays along. So that’s where he wanted to start. He didn’t want to be distracted [by the music].

Whenever in the film you hear music in the film that associates with the dance, like for instance “Septet” or “Suite for Five,” that was actually music that was used onstage and I was actually trying to be very religious about that because I can’t put Philip Glass there or anything else. It’s not a free-for-all. I’m working with something that was created. It’s not of my own making, so I cannot jeopardize the integrity of that. But if we’re in an environment [created for the film], I felt we had full license to create a sound environment for a piece because Merce was known for these performances where he’d come to a location, inspect it and figure out what would work for that location. He could pull from any dance and then a new dance is born and he would commission music for that particular performance, so I felt there was creative license in a sense to be open to possibilities and create the environment’s sound.

For instance [with] “Winterbranch,” where we basically create a club downstairs that’s throbbing music that’s coming out of that club, it’s completely created [for the film], but I feel it’s totally within the spirit of what [Cunningham] could’ve done, so it was a very careful process and one of the challenges because of course, you go well, on stage it’s okay to listen to this kind of [avant garde] music, but on film it’s impossible. People are going to leave. There are all these fears because it’s not “Swan Lake,” so there was a tension about that, but I never wanted to jeopardize that.

What’s it like to get to the finish line?

I’m actually moved. I didn’t expect this reaction because what’s amazing about this process with all these amazing people onboard like Dogwoof and Magnolia and so many other distributors is I feel I made the movie I wanted to make. Nobody pressured me or worried that this is going to be accessible or people are going to watch it, but what’s most interesting is I wanted to bring it to people who don’t know anything about dance. Of course, there are Merce devotees, but I really feel dance is something that brings us all together. It’s an underdog of all the art forms because people see it once and that’s it, so I wanted people to have an experience of it through cinema because I think that’s where the power lies.

And the reactions are incredible because they all say it’s an experience. They all feel like they’ve been through something. They are more interested and they may want to see something on stage, and I think the cinema was a physical on-ramp. It’s best at action and images. All early actors come from physical comedy – vaudeville and circus, they are the ones who made cinema what it is. And right now, we have stars who don’t know how to move. They can look good and they can speak well, but that’s not the power. The power’s in the gesture. The power is the body language. The power is how you walk from here to here. You can say so much. That’s what cinema is good at. So I’m on a mission in that sense. I feel like we need to revive that, and it’s incredibly inspiring we could do this with this movie. We could do it with other movies.

“Cunningham” opens on December 13th in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal and the Arclight Sherman Oaks and in New York at the Film Forum and Walter Reade Theater. A full schedule of theaters and dates is here.