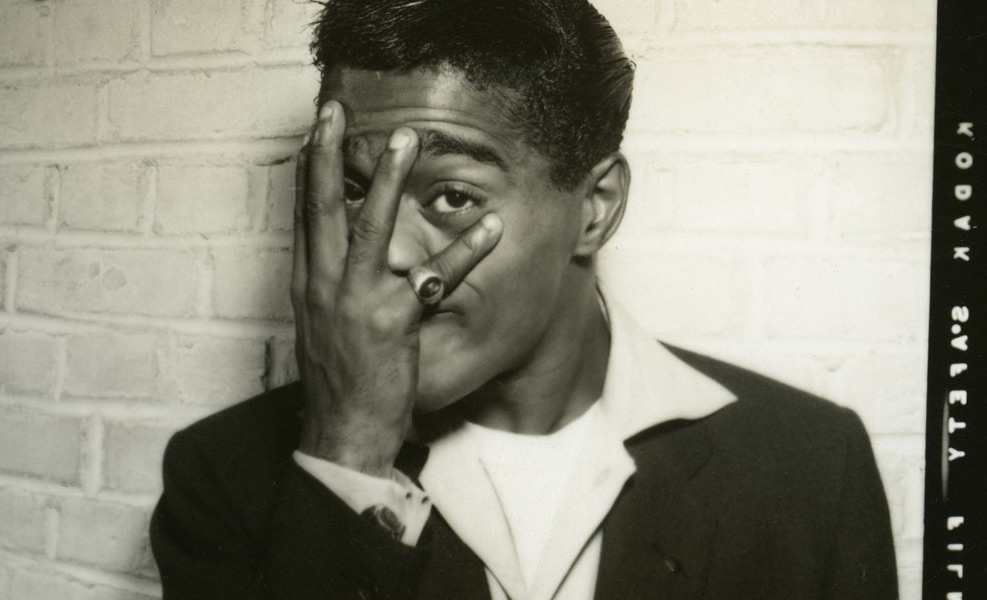

After spending years working towards a documentary about the consummate entertainer Sammy Davis Jr., it is not surprising that when “American Masters” producer Michael Kantor and writer Laurence Maslon needed a director for the project, they turned to the current hardest working man in show business, Sam Pollard.

“I’ve got to say, it’s been a pretty decent year,” said Pollard during a rare break for the editor/director before his latest film “Sammy Davis Jr.,” I’ve Gotta Be Me” premieres at the Toronto Film Festival. “Last year, I ended up with a film I directed called “Two Trains Runnin’” about the search for these two great blues musicians and I finished up the Sammy film at the same time the ACORN film [“ACORN and the Firestorm”] was being finished [for] Tribeca, and I just finished a film about the first black mayor of Atlanta, Maynard Jackson, and I’m working on a film I directed about voter suppression and voter fraud called ‘Rigged.’ So I’m feeling pretty pleased with how things are going at the moment. They can always change.”

Pollard has often been an agent of change himself, often delving deep into African-American cultural history to inform the present and his latest is no exception. A vibrant and compelling portrait of a man as famous as he was misunderstood, “Sammy Davis Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me” draws on the singer/dancer/actor extraordinaire’s considerable archive to speak to someone who was thought to transcend race as a member of the Rat Pack but spent his life using discrimination as inspiration for creative invention, whether it was becoming a wicked impressionist when he realized it was more effective than his fists at defending himself in the military or singing standards by white composers and made them into his own. With fancy filmmaking footwork that the brilliant tap dancer no doubt would admire, Pollard and editor Steven Wechsler shrewdly organize the film around Davis’ many talents, charting how each of his professional skills were birthed from his personal life, leaving plenty of time to enjoy performances from his heyday that remain jawdropping while not shying away from how his political naivete left him vulnerable to those wanting to take advantage of his popularity, such an an infamous hug he gave Richard Nixon on the eve of Watergate.

Featuring countless interviews with friends and associates, not to mention considerable insight from Davis’ own testimony, “Sammy Davis Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me” proves to be as engaging as its subject and recently, Pollard spoke about how he corralled a career that spanned nearly six decades into an electrifying hour-and-a-half profile.

Originally, there was a different director onboard, but had to leave and I took over and to me, it was a great honor and a pleasure because I grew up watching Sammy performing, so I was very familiar with his life. The thing that excited me – that always excites me when I’m doing these kind of films, [since] I’ve done other “American Masters” – is that when you think you know a subject really well, you do some more extensive research, and you see how much you don’t know about a person. I knew [Sammy] was a great dancer, a great singer, and a great impressionist. But I didn’t really know the extent of what he had to confront as an African-American male, growing up in the ‘30s, the ‘40s, and the ‘50s and the [cultural] breakthrough he had, dealing with the loss of his eye, his conversion to Judaism, his skyrocketing to fame and his relationship to Sinatra and Dean Martin, and the pushback he got from being involved with white women and his marriage to Mai Britt. All those things I didn’t really know the details [about] until I got involved in the research.

It’s inspired that you organize the film into chapters around his many talents and different facets of his persona rather than follow a strict chronology. How did you figure that approach out?

That was one of those things that happens during the editing process. Larry [Maslon] had written a script, which looked at his life in a pretty chronological perspective, but then as myself and my editor Steve Wechsler started to put the film together, we started to think even though it’s going to be chronological in many places, why don’t we look as his film in terms of the themes that stand out — his work as a dancer, his work as a singer, his work with wanting to be on Broadway, his relationship with Sinatra — and as we start to build up a structure, we started to really focus on those things. It was one of those things in the editing room where I’m like, “Why don’t we put a card in here that says Sammy as a dancer, Sammy as a…” We had some early titles that we changed along the way, but it gave us some grounding to be able to jump around chronologically within certain segments, which is something that’s always surprising to me in the editing process – how you come up with some new ideas and make things happen.

Despite having interviews with virtually anyone you’d probably want to talk to, you seem to allow Sammy to tell as much of his own story as possible. Why was that important?

One of the big finds in the research about Sammy was all his audio tapes that he had done when he was doing a sequel to his book, “Yes I Can,” with the writers Burt Boyer and Jane Boyer. It was very insightful to listen to all these audio tapes of Sammy as he’s talking to these two other writers about his life and his trials and tribulations and we all felt — myself, Larry Maslon, the writer and Michael Kantor, Sally Rosenthal, the two producers— that it was important that you heard Sammy in the first person and you heard Sammy’s voice. We went through those audio tapes three or four times, trying to find the best moments that we thought would add nuance and different perspective to his life where Sammy could really give you some insight and depth in terms of what he was thinking and how he was feeling about what he was involved in at that particular moment.

For [“Golden Boy,” which Sammy performed for three years, on and off, on Broadway] there wasn’t a lot of footage — there was a great amount of stills that we used and Paula Wayne was great at talking about the show, and we had the Playbills and stuff like that — but this is one of the places where Sammy had done some really interesting audio about working on that show, working with Arthur Penn, who became the director of the show before it went on Broadway. And the [other] example that I would give is his response when he was disinvited by the Kennedy [Inaugural] Gala in 1960 [while the rest of the Rat Pack, as well as Harry Belafonte and Nat King Cole were on the guest list] and the pain and the feelings of hurt that Sammy articulates, talking about being disinvited to the gala [after] being so prominent in helping John Kennedy become president of the United States, along with Sinatra and Dean Martin and other members of the Rat Pack.

Again, that was one of those things in the editing process [where] we probably had three or four different ways of opening the film. As we started to really hone in on the final structure, the one thing that we always knew we wanted to deal with from the very beginning was that Nixon hug because it’s such a big moment in Sammy’s life. It caused such tension and conflict for him and then the response that he got when he went out to Chicago to Operation PUSH [event “Save the Children” in 1972]. Because that was a pivotal moment that we didn’t want to wait to keep it till the end of the film and we wanted to give you a tease and make you understand why Sammy Davis, the title is so appropriate – “I’ve Gotta Be Me.” No matter who he was, he was going to be the man that he had to be no matter what the reaction was from his audience, from his fans, from those who disagreed with him, he still had to be Sammy Davis and he took the brunt of that hug, which is very painful as you see in the film.

This is something you make look so easy, but it’s likely pretty difficult when you’re presenting a variety of different perspectives in interviews that are at odds with one another about Sammy’s motivations or his intentions — how do reconcile them in a way where you can either guide the audience to the truth of what happened, if there is such a thing, or let them come to their own conclusions?

I’m a believer that you try to grab the audience so that they have their own opinion. You’re always going to try to shade it to what you think you want the audience to feel, but you try to give it a little nuance. You don’t want to articulate what these people say in interviews and just make it black and white. Because life isn’t that way. And Sammy wasn’t that way, like most human beings. So as a filmmaker, I’m always trying to shape the film with the interviews and with the archival footage in a way where the audience has the room to have an opinion about it. It doesn’t clearly say Sammy was bad to hug Nixon, it doesn’t clearly say Sammy was good to hug Nixon. We leave it to you, the audience, to decide. And Sammy tells you, “If you want me to sing, I’ll sing. If you don’t want me to sing, I won’t sing.” And the audience, even though they may have had issues with him after the Nixon hug, they said, “We still respect you as an entertainer, so sing.”

When you have so much material at your fingertips, is it actually easier or harder to connect the dots?

It’s like a plethora of goodies. There’s so much material of Sammy Davis Jr. that I looked at – the live performances, the taped shows he did, the movies he did, the tours he did in Europe. We watched so much material that sometimes you could feel overwhelmed, but we felt it was great to have access to so much stuff which we’re able to pick and choose the ones that we thought were the most tangy and the most interesting in terms of Sammy’s life and career.

There’s such great stuff of him in the ‘50s on “The Eddie Cantor Show” and “The Ed Sullivan Show” that every time we watched his performances, we were looking at, “Is this moment going to be good for the dancing [section] or his impressions?” We would watch him doing the different impressions over the different decades and we’d go back and really analyze which one we thought was the most provocative, the most engaging. The same with dance. There’s a beautiful dance segment in the film that we really let play for like two minutes – it’s from the 1950s, where he’s just phenomenal and you’re just watching him dance with these two drummers and he dances by himself as the drummers play in the background. It’s just magnificent to watch him at the height of his career, and the same thing with the singing. I listened to all of his records, making sure I listened to see which songs really made Sammy stand out. I grew up on all those standards that he sings so well, so it was a real pleasure to go back to listen to him singing Gershwin and Cole Porter, and all these different songs from the different composers and find the ones that we thought helped connect you to his life.

I’ve got to tip my hat to Larry Maslun, the writer. He knew some people from the Gershwin estate, so he and Michael Kantor reached out to them and we still had to pay them a licensing fee, but not as much as we thought we’d have to pay to get them to come onboard. We wanted to use that clip, but as you know, “Porgy & Bess” is rarely seen, so it was great that they came onboard and let us use a clip of that great moment in that film.

Since you expressed surprise earlier when you dove into the research for this, did the film evolve into something different than you thought it’d be?

I walked in knowing that I always thought Sammy Davis was a great entertainer, and probably after so many years, he had dimmed in my memory, so this was like a reawakening, a reacquaintance with this great man, this great talent. The other thing I came away with was that Sammy Davis Jr., no matter with all the skills and talent that he had, he struggled mightily every day to be a human being, to engage with people and to interact, to be accepted, to feel rejection, to deal with hurt, and to deal with pain. And those are things that I find fascinating about any person that I deal with in making a documentary – that you see that at the core of them, we’re all human. No matter how much money we have or talent we have, we’re all human and we all feel some kind of pain in our lives. And that, to me, no matter how many times I do it on a film or with a subject like Sammy Davis Jr., is always a revelation.

“Sammy Davis Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me” will premiere at the Toronto Film Festival on September 11th at the Scotiabank 13 at 9:45 pm, September 13th at the Scotiabank 2 and September 15th at 9 pm at the Scotiabank 13.