“I saw these guys doing whatever the hell they wanted to do and thought that was the job for me,” says Samantha in “Tomboy,” recalling coming of age during the ‘80s right when Motley Crue burst onto MTV, making the radical enough notion that she’d have access to cable in the suburbs that much more unbelievable. It would’ve truly blown her mind to let her imagination drift to the point of believing she could ever sit where Tommy Lee was, just behind Vince Neil, on the drums, though after a stint in Hole during their rise to prominence, she’d ultimately come to fill in when Lee left the band, more incredulous than anyone else that a woman would ever play onstage with the famously testosterone-heavy hair band.

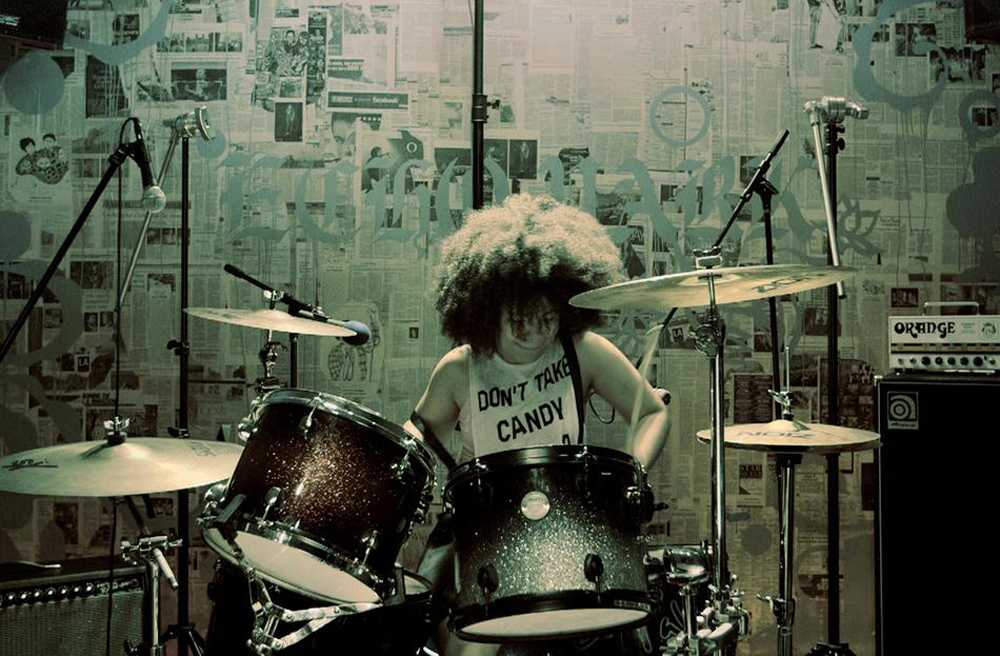

It’s a lonely road, but not one that’s entirely unique as Lindsay Lindenbaum illustrates in her ever-intriguing and impressionistic paean to female percussionists. For a story of women who set the rhythm, the director/cinematographer quickly establishes an unusual one for the film, drifting in and out of the lives of four drummers at different stages in their lives and careers, from Bo-Pah, a teen who was given pots and pans to bang on by her parents when her three sisters picked up guitars, Chase, who can be seen touring with the grrl group Boytoy, Samantha, who has retired her drumsticks for the life of a music exec, and Bobbye, a pioneering studio musician for Motown at their height. Lindenbaum doesn’t immediately introduce any of the women with their credentials, slowly letting the realization dawn on those unfamiliar that Samantha was there for Hole’s commercial breakthrough upon seeing intimate backstage videos of Courtney Love and others fooling around backstage and the wicked riff that underscored Bill Withers’ “Grandma’s Hands” (and later became the hook for Blackstreet’s hit “No Diggity”) was all Bobbye’s, but that serves to put them on equal footing, traveling the same uncertain path at different times.

Reminiscent of Alma Ha’rel’s similarly elusive and sensational meditation on heartbreak, “Lovetrue,” “Tomboy” shrewdly acknowledges that to give shape to a deeply personal experience would be somewhat dishonest when it could feel so amorphous, yet occurs commonly enough that there are relatable touchstones and it gradually takes hold as you see how music can put things in perspective for its characters and also is what throws things out of whack when Bobbye can look at a picture of touring with Bob Dylan and think only about the time she missed with her young daughter while out on the road and Chase begins to wonder if all she has in common with her bandmates is the music they play. There’s both slight comfort and concern in Lindenbaum’s coverage of an entire age spectrum of artists where both survival and regret can be seen at the end, organically implying all the sacrifices that inevitably had to be made that you can never see for those just starting out, but in subtly and effectively making this point among many others, the rock and rock spirit is what shines through in “Tomboy,” as distinctive and singular formally as any of the women it follows.

“Tomboy” does not yet have U.S. distribution.