Just after Berlin is reduced to rubble towards the end of World War II in “Never Look Away,” director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck intersperses a static shot of crumbled tin foil that takes up the entire screen amidst painstaking recreations of the fall of Nazi Germany, a juxtaposition in which the simple imagery is allowed to carry a far more weighty and direct sensation than the far more technically complex scenes which the filmmaker had to spend months preparing for, yet all in the service of a film that you could feel, both in the depths of the soul and at the tip of your finger.

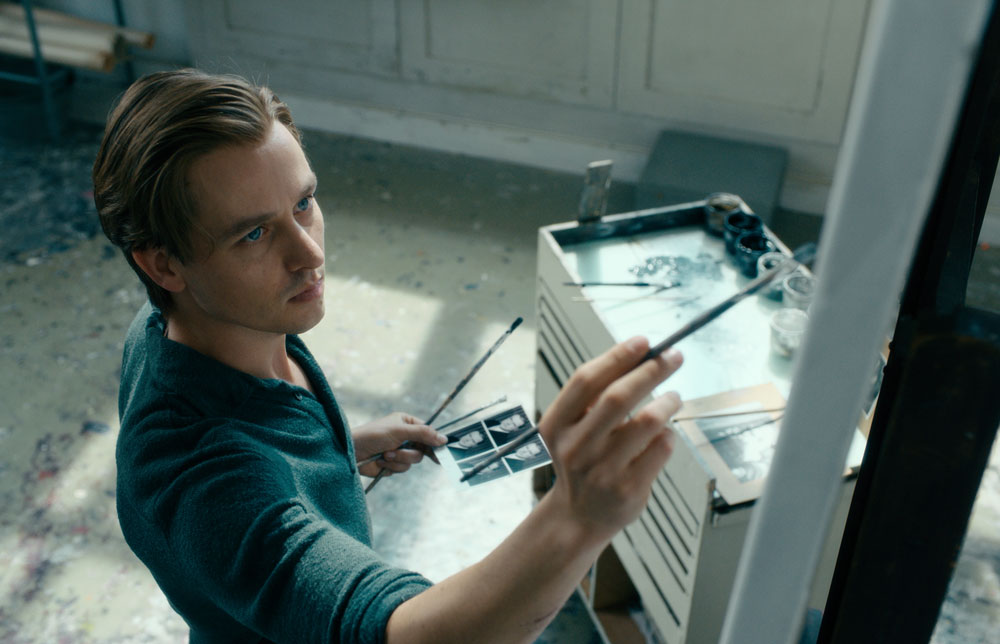

“With artists, we think of them as somebody who just uses their eyes, but making art is very physical, so I wanted to give the film a very physical dimension,” says von Donnersmarck, not exactly referring to himself but rather Kurt Barnert (Tom Schilling), the aspiring painter at the center of “Never Look Away” through whom the writer/director takes a look at his nation’s tortured history and celebrates the power of art as a way of making sense of it.

In returning to his native country for the first time since the Oscar-winning “The Lives of Others” in 2006, the filmmaker shows the same level of ambition that one would expect of Kurt in the early stages of his career while displaying the skill that has come with time. A drama that spans the rise of the Nazis during the 1930s to the swinging 1960s, “Never Look Away” follows Kurt from when he’s just a boy in Dresden, inspired to consider art as a career from a museum visit with his aunt Elisabeth (Saskia Rosendahl) and finding himself taken with a Kandinsky painting, as well as perhaps the mention that it’s price tag of 2000 marks is more than most German workers make in a year. While he’s quickly disabused of the latter reason to pick up a paint brush, the way the art can stir the emotions inside of him never leaves, pushing him towards art school at a turbulent time for all of Germany when many of his peers faced the choice of using their talent as a powerful tool for rebellion and risk persecution from the Nazis or assist the propaganda efforts to seemingly assure their survival.

After seeing Elisabeth hauled off as a child, all but knowing she was consigned to death for her mental instability by a regime that sought purity in its citizenry, the choice isn’t a difficult one for Kurt, but expressing himself is since he has yet to discover what makes his voice unique and the influence of various mentors and peers may be tainted by political considerations as much as personal preference. Matters are complicated further when he falls in love with Ellie (Paula Beer), a fellow student who works towards a career in fashion design and whose father Carl (Sebastian Koch) is a prominent member of the German medical community. Beyond the tension of her dad disapproving of the financial returns from the life of an artist, something else doesn’t sit right between Kurt and Carl and in pitting them against each other as well as drawing a parallel between them, von Donnersmarck crafts a compelling portrait of cultural attitudes as well as a bewitching mystery in what they come to represent, one trying to open people’s eyes to move towards the future and the other desperately trying to hold onto secrets of the past.

During our conversation, von Donnersmarck alluded to finding himself at a similar chronological crossroads, not in geopolitics, but in cinema, boldly making a three-hour-plus epic that many over the years likely suggested would be a better fit for a streaming service like Netflix and to be broken up into episodes. Yet “Never Look Away” is the grand immersive experience people have sought from the movies since the medium’s earliest days with a story that deepens with the filmmaker’s assiduous attention to historical context and the sense of discovery within Kurt’s evolution as an artist that feels autobiographical for von Donnersmarck. While the director was in Los Angeles for AFI Fest, he spoke about the time it took to get “Never Look Away” off the ground, recruiting the legendary cinematographer Caleb Deschanel to come onboard and how he could bring some of what he learned from his first foray into Hollywood with the Johnny Depp-Angelina Jolie thriller “The Tourist” back to Germany.

There was this quote that I read from Elia Kazan — “A Life” is one of my favorite books on filmmaking and he talks about his work with Marlon Brando and Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. He’s generally worked with geniuses and he says that he felt that their artistic talent was merely the scab that had formed on the wounds that life had dealt them, mostly in childhood. I thought that was a really interesting way of looking at art – that basically, the grand gesture of the artist is trying to protect their wounds, and it’s an analogy that you can carry quite far because if the wounds are still bleeding, you can’t create art. If it’s healed, you can, but if the wound was significant, the scab will be big. So I thought I’d love to find a way to explore that theme in someone’s life and show how the terrible things we all go through in life are somehow put to use in a positive, productive way, almost a little bit like in in “Slumdog Millionaire,” [where] all the terrible things the guy went through suddenly mattered because he could answer all the quiz show questions. It’s like that in real life, except the quiz show is life.

So I first looked for this story of an artistic genius in opera because somehow I thought it would be really cool to have a composer who has misfortunes in life and love, but goes back home after we’ve experienced all that and puts that all into music, and I looked if there was a story somewhere in one of the operas that I liked, but there wasn’t anything [in history] because it was mostly composers writing on commission some libretto that was either a best seller or a famous play. Then a journalist I met had written an article on the painter Gerhard Richter and had found out one of his paintings — of a very beautiful young woman who is holding a little baby — and was of his aunt who was murdered by the Nazis because she was schizophrenic and the baby was him. Richter was 30 when he made that painting, but the journalist found out the father of the woman that Richter ended up marrying was an SS doctor who went undiscovered and unpunished and he’d been in charge of the euthanasia and forced sterilization program, and [only] found out when he was already an old man. I thought this was really interesting because I liked the idea of this rich, powerful super-intelligent doctor and this young artist who has no money or power, and maybe is not even particularly eloquent or brilliant, but still manages to find out something that this guy has been trying to hide all his life, so that was the starting point.

Luckily, I had a few terrific artists consulting us on this and then we had a really great painter who actually was a star student of Gerhard Richter’s and a long time assistant to [him] who created the paintings for us. But [overall] it was a long path towards finding them so they’d have artistic integrity. What was really interesting was reconstructing the Degenerate art exhibit at the beginning [of the film] since a lot of those paintings were destroyed by the Nazis, so there were only little black and white pictures of them. We had to recreate and paint them again in full size, working with the archives of these painters and with art historians, trying to reconstruct them exactly as they would’ve been, so we employed a lot of artists [to do that].

Speaking of artists, how do you bring on Caleb Deschanel as your cinematographer?

He’s great, isn’t he? Yeah, I always knew I wanted to work with Caleb — and I also know he passes on almost everything — [because] probably my first experience of cinema as art was “The Black Stallion.” I saw that at an open air theater in New York at age seven or so and it was Caleb’s first film as a DP. I was blown away. I thought, “How could someone look at the sun like this? And at shadows?” It was unbelievable and when I had this idea, I wrote to Caleb and said, “Could I meet you just to tell you about an idea that I have?” And in the end, I ended up telling him the whole film scene-by-scene. I think it took five hours because I described it in even more detail than is in the film. [laughs] I told him every little last bit and he said, “Okay, I find this very interesting. I’m in.” It was really quite extraordinary because it was a tough and complicated shoot that we had, but he’s really a genius and for him to go to Germany for half-a-year, I’m glad that you mention him because he deserves so much to be recognized for this.

Yeah, I don’t like it when you have to make a virtue out of a necessity — I think there should only be virtue throughout, but it was a really great, interesting experience making “The Tourist,” and I had experienced what incredible makeup can do. [We had] these unbelievable Italians who do all of Baz Luhrmann and Paolo Sorrentino’s films, so I said to them, “Look, I saw what you could do on “The Tourist,” how would you like to put this in the service of a German art movie?” [laughs] “It’ll mean a lot less money, but it’ll be satisfying and you will accompany characters through 30 years.” And they said, “Okay, we enjoyed working with you [before] and this seems like a fun challenge.” So that was one thing, though they weren’t quite expecting how cold Germany could get. And the incredible experience of Caleb Deschanel helped us tremendously in that he’s not someone who’s willing to make any compromises. He knows what a perfect result can be, so if you can’t solve it by throwing money at it, he’ll find another solution, so I do think the experience of “The Tourist” helped me in seeing what the top standard of technical filmmaking is and not accepting any less.

It’s interesting to hear about that you walked through the film beat by beat with Caleb Deschanel because I understand for even roles that have a single line, you’ll want to have a conversation about the part. Is that a two-way street, as far as developing the characters?

I always pay very close attention to the actor’s reaction to anything. If the actor has a problem with a scene, I try and explain it and if he or she still has a problem, then I know there’s something wrong because the actors’ understanding of a scene is deeper than anybody else’s because they have to live it. I’ve often eliminated lines or scenes or added them because of the reaction from an actor, so absolutely it’s a two-way street.

To go back to Caleb Deschanel, one of the most important things in his work is not just the unbelievable light that he does or the great storytelling that he’s capable of through images, but the fact that he has a deep understanding and love for actors – being married to one and having two actor daughters, he gets that’s the most important thing in a way that I haven’t seen with other directors of photography. He understands that we’re all just putting our work in service of what truly creates the emotion – the acting.

After carrying this with you for some time, what’s it like to put out into the world?

It felt very good. We’ve had very, very positive audience reactions and that’s a great thing to experience because any form of artistic expression is communication. I say “Okay, here is the way that my actors and I see the world” and if someone else says we like seeing the world that way, then that makes us feel like less alone. In that way, it’s been a beautiful communal experience, which is one of the great things cinema can do, and it’s why I’m not yet willing to accept this type of cinema is supposed to move completely to OTTs and television. There is a beauty about the collective experience, about the way that it raises our perception and intelligence. I feel a lot smarter sitting in a movie theater than I do watching something alone at home. [laughs]

“Never Look Away” opens for a one-week awards qualifying run on November 30th in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal. It will open in wider release in 2019.