There’s a new piece of equipment that Eric Branco picks up before every shoot, one that has nothing to do with the camera he shoots on.

“It like a running joke with the white Adidas, but I do find I operate much, much better in running shoes than when I’m operating in boots,” says the cinematographer, whose fresh pair of kicks has no doubt contributed to the fresh perspective of the films he’s worked on. “People maybe don’t think about the athleticism that it takes to operate a camera handheld and to be moving, but it really is about being able to feel the ground underneath your feet and be hyper-aware of your own movement. I was also a gymnast before getting into the film, so all of that emotional and physical awareness and being in control of one’s body definitely contributed in a major way to my operating [the camera].”

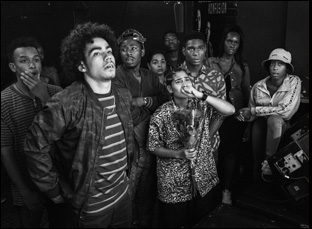

Branco needed to be fast on his feet to keep up with writer/director/star Radha Blank in her debut feature “The Forty-Year-Old Version” about an Black playwright making moves after her career has stalled, once seeing her name bandied about on “30 Under 30” only to find that in order to get her work produced, she’d need to bend to a system where her work was largely reduced to what white gatekeepers, however well-intentioned, were willing to produce. She finds inspiration in freestyle rapping where no one but a young producer named D (Oswin Benjamin) is around to cut her mic, dropping fierce rhymes about being forced into the corner of writing “Poverty Porn” at night as she spends soul-draining days tending to the upcoming production of her play “Harlem Ave,” and Branco’s dynamic camerawork plays no small part in the gradual recognition both externally and internally of what the onscreen version of Blank is capable of as an artist, following her lead in unearthing grace wherever she can.

Quite literally capturing all the shades of grey that occur on the journey to makin’ it with a savvy use of monochrome, Blank and Branco give the camera as strong a personality as its central character, full of snappy whip-pans and gorgeously composed shots of the New York City at night where the possibilities seem endless. The versatility within the film is remarkable to segue from outrageous comedy to tender introspection, but Branco, who is as agile creatively as he is physically, shows considerable range a year removed from his haunting work in Chinonye Chukwu’s death row drama “Clemency” where he captured a warden’s decisions from one devastating angle after another. With “The Forty-Year-Old Version” now on Netflix following its premiere at Sundance earlier this year, the cinematographer spoke about finding the right cinematic language to match Blank’s way with words, how his background in acting has helped him create an environment for those in front of the camera to lose sight of it and the preparation that went into working with film stock to yield a work that’s luminous in so many different respects.

The whole interview could probably be this question, but every director is different. What was different this time because she was wearing so many hats on the set was that camera movement was really under my purview. A lot of times directors will be directing the movement, you’ll do rehearsals and they’ll watch the rehearsal and you’ll take notes and make adjustments, but that was much harder because [Radha] was in the scene herself probably for 95 percent of this movie, so my biggest responsibility was handling the movement of the camera. All of the conversations about this movie were really centered on that documentary feel, shot on 35, black and white, and the idea that the camera should lead your eye. The camera should tell you what’s important right now, and handheld was always part of that mandate. It’s one of those things where I can’t see the movie any other way in my mind aside from the movie that we did shoot.

You establish the comic tone early on with whip-pans, but as the movie wears on, you’re able to use the move for dramatic purposes. Was that elasticity of visual language something you had to consider from the start?

Radha and I both have a really strong sense of story and hopefully when you’re watching a movie that I shot that Radha directed, the audience is not going to be left on their own to sort things out, so from a dramatic standpoint, there was a very, very clear understanding of what the camera was doing, what new information we were presenting and how we wanted the audience to have this information presented to them, and then a layer beyond that is using comedy to probably soften audience expectations and hopefully leave people vulnerable to the real emotional issues of the film. In our case, the handheld whip-pan language is not often used to land big dramatic blows, so part of the fun that we had developing the language of this movie was that maybe the first two-thirds of the movie are really about setting the audience up and then in the last act, it’s really about like these big emotional and real feelings. A lot of people are calling it a comedy, which it is by all means, but I think it goes beyond that into talking about this feeling that a lot of artists have of “Am I good enough?” “Am I doing the right thing here by continuing this life?” “And will acceptance in my field even bring me emotional stability that I’m seeking?”

It’s a tribute to how you’re able to allow a real vulnerability come across on screen given that I’ve heard you started out as an actor, are you conscious of how you’re creating those spaces for them to work in?

Yeah, you very often hear that people are an actor’s director, but I definitely like to think of myself as an actor’s DP. I put a lot of thought and care into how the actors are going to feel in a space and how I can build a working environment that’s full of trust and will allow actors to feel safe and really do their best work uninterrupted. I don’t know if I would have the skill set if I hadn’t started in acting myself.

No, I will say that the opposite of what you just said actually necessitates me using larger equipment and bigger lights and bigger rigs in order to do the same thing without the lights interferring. Sometimes there’s no way around it and you have to put a light almost between two actors, which has to affect their emotionality in a scene, and every actor is working at a caliber where they can get the job done, but rather than putting a smaller light closer to an actor where it might be in their eyeline.

A lot of the night exteriors on “40” — our street scenes and things like that, the lights were coming from buildings across the street, so hopefully when the actors are on set, they’re not seeing my cranes. They just feel like they’re in the world, hopefully. Specifically, there’s a scene maybe halfway through the movie where after the first or second rehearsal [of “Harlem Ave,”], Radha and her agent Archie [played by Peter Y. Kim] and Jay Whitman [the producer, played by Reed Birney] leave a rehearsal and have a brief conversation on the street outside the rehearsal building, and they notice that D is waiting for Radha, so to light that scene, we actually rented office space in the building across the street [to] set our lights up in the windows – I think it was the 10th floor – and lit entirely from the building across the street. They weren’t large lights by any means. They were smaller Lekos, and they all fit in a bin we took up in an elevator, but it’s that solution-oriented thinking I’m proud of where you’re making a small movie in New York and we’re like, “Okay, we can’t lock down the street, our permit won’t allow us to have a crane up here and our shot needs us to pan like 270 degrees, so where am I going to put a light here?” Every time I see that scene, I’m proud that it looks like night in New York, it looks real and the lights are hidden.

You’ve said in other interviews that you were actually becoming quite interested in how to capture a variety of skin tones on screen before the script for “40-Year-Old Version” came to you because of your work on another black-and-white short, Marshall Tyler’s “Cap” – what went into getting the right mix to get this look?

Yeah, I shot this film “Cap,” which was a very low budget thing on my usual filters that I use. I primarily shot it using orange and red filters and while I’m very happy with the way “Cap” looks, it spurred in my this idea that we could go a little bit further and I could develop my own filtration techniques for darker skin. One of the things that I had been using when shooting in black and white was color filtration, which had been a standard part of the language prior to the invention of color film, but it had become a niche thing [today], and one of the things I discovered through my own studies was that darker skin people had not really ever been photographed with the care that caucasian people had. By the time African-American filmmakers were making their own movies, black and white was a thing of the past, so while filters had been developed to improve complexions or make skin tones pop with whiter skin, we did not have the same thing for darker skin.

As a filmmaker, it’s one of the few art forms that you can’t practice alone and you’re always trying to hone your skills and keep your muscles strong, but the decisions you have to make in these moments just can’t be done unless you’re on a set, so you have to find other ways to hone the skill. One of the ways that I had been practicing on my own was I had decided I had been using color too much to draw the eye, so I actually sold my digital camera and bought a film camera and a kajillion rolls of black and white film and I really just spent probably a year just photographing in black and white. Then I was actually at a rental house in L.A. just testing these filters on my own when I got outside and got to my car, I checked my e-mail like you do, and the script for “40 Year-Old Version” was sitting in my inbox. On the title page, it said, “A New York Tale in Black and White,” and it can’t get more serendipitous than that.

With “40,” it was one of those things where we tested filtration a ton and it was really a matter of digging through the basement [at the rental house] because a lot of these black-and-white in-front-of-the-lens filters, since the move to digital, has fallen by the wayside a little bit, so a lot of the filters that I knew and had used when I was in film school or worked with very early on in my career are now relegated to the basement storage. When we started “40” and we started testing, I was like an old record collector in the basement of TCS in New York, going through all these filters and finding all these things I thought I could make combinations of work for darker skin tones. While the solution was never a one-size-fits-all filter, we developed several kinds of cocktail recipes for filters that I think worked really well for us.

Yeah, Radha and I dealt with some pressure early on to not shoot on black-and-white film. Most movies that are black and white don’t actually originate on a black-and-white negative, even discounting black-and-white films that are shot digitally say like “Roma” or “Frances Ha.” Modern films that you think of like “La Haine” or “Good Night and Good Luck” were actually shot on color film and printed on black and white stock, which when I found out “La Haine” was shot on color, my dreams fell apart. [laughs] So shooting on black-and-white not only locks in choices on the set, but also committing to the fact that you’re going to have a longer turnaround between shooting something and seeing dailies.

In our case, not to throw anybody under the bus here, but there was another filmmaker working in town by the name of Steven Spielberg, who was doing the “West Side Story” remake at the exact same time as we were shooting and he really had tied up every bath at Kodak in New York with his processing, so Kodak didn’t really have the ability to switch over an entire tank to black-and-white for this little indie film. That necessitated us finding Colorlab in Maryland, who were over the moon that we were going to them, and they were instrumental in developing this look with us. I can’t say enough how amazing the experience of going with them was and we had extensive conversations about the look and what we could do in processing, but it was probably a four-day turnaround, maybe at times five between shipping the film down, getting the film developed, getting the film shipped back. Then we scanned the film in New York at Metropolis Post and then those were all uploaded then to an online center where we could view dailies.

Unbelievable. It’s just remarkable what made it onto the screen.

Yeah, and for me, if the dailies take longer than a week, I guarantee myself one week of job security. [laughs] If it was a color film, they could’ve fired me on the second day, but on this one, they had to wait as long as five days to fire me. [laughs]

“The Forty-Year-Old Version” is now streaming on Netflix.