Tiller Russell still can’t believe he survived the making of “The Seven Five.”

“It was one surreal and strange experience after another,” said Russell, who may not have lived in New York during the height of the city’s turmoil during the late 1970s and early 1980s, but got more than a taste of it while filming. “I remember when I was first meeting [one of the film’s subjects Michael Dowd], he was having me get on and off the train [in certain locations]. I felt like either I’m going to get shot, or I’m going to walk out with a holy-shit story here.”

Even if I wasn’t going by the fact he was speaking to me recently, it’s safe to say Russell got the latter. With “The Seven Five,” the director who last saddled up with the western “The Last Rites of Ransom Pride,” tames an even wilder beast than any of the horses he dealt with on his previous film in the real life story of Dowd, a thoroughly dirty police officer who with his partner Ken Eurell and associate Henry “Chicky” Guevara turned a $600-a-week job into an $8000-a-week gig by aligning with the cocaine kingpins he was supposed to be putting in prison.

Filled with the kinds of details you couldn’t possibly make up, Russell flips the phrase “in too deep” from a damning statement of the integrity of the crooked precinct in Brooklyn, into an affirmation of his doggedness, tracking down every one of the major players from the cops to the criminals to testify to Dowd’s illicit adventures, beginning so humbly with a routine traffic stop-turned-shakedown to eventually staking out locations that the DEA had an eye on to rob them at the behest of Puerto Rican drug kingpin Adam Diaz. “The Seven Five” allows the audience to experience the same rush as Dowd did without having to serve time, thanks to lively interviews and actual footage from local and federal investigations. (It’s no wonder the film is already being adapted to a narrative feature by “Out of Sight” scribe Scott Frank and “’71” director Yann Demange.)

Shortly before “The Seven Five” hits theaters this week, Russell spoke about his ability to find people who don’t want to be found, an unusual interview process that gave the film its electric energy and what it was like to bring everyone together – including those who had turned on one another – for the film’s crazy DOCNYC premiere last fall.

I had the chance to work with a couple of great producers, Eli Holzman and Aaron Saidman, who had a longstanding passion for the project. They asked if I knew about the story and whether I thought there was a film there, and I said, “Look, give me a couple of months, and let’s see what I can find and who’s willing to talk.”

I began using the software that bounty hunters use to track people down because many of these people wanted to disappear. They’re cops, so they knew how to do it in a pretty sophisticated way, whether it was assumed identities and or buying social-security cards or whatever it may be. I knew they were going to be super-skeptical and paranoid, but I also knew that no matter who you are, whether you’re a celebrity or a homeless vet, you’re going to answer a FedEx if you get it. So I started writing these lengthy personal letters to each one of these people that I could track down, using a matrix of their known associates and previous residences and criminal records. Little by little, I began to hunt people down.

Universally, to a man, they completely flipped out when I got them. They were like, “Who the hell are you? What do you want?” But weirdly, exactly the right amount of time had elapsed where these guys had done the crimes, they’d done the time — still young enough to tell the story, but enough time had passed that it wasn’t too raw and sensitive either. So I said, “Look, meet me eye-to-eye, man-to-man. If you think I’m full of shit or you don’t trust me, walk. If you think that I’m the guy that can tell your story in an honest and compelling way, then let me make a run at it.”

I started jumping on planes and meeting people in strange, almost like drug-dealery kind of scenarios where they change locations and have me move from one venue to another, so they could check me out and make sure I wasn’t being followed and I was who I said I was. Then it was the sweet spot where everybody was oddly confessional and willing to tell their story in a shameless, direct, bloody and direct way.

Once I began to meet these people, it was like stumbling into the middle of a Scorsese movie where you’ve got not just one or two [characters], but a crazy cross-section of characters that are equal parts hilarious, harrowing, horrifying, and riveting. It was like, “Holy shit, this is a really fascinating world,” and as far as I know, nobody has ever really been able to penetrate that and tell, from an insider’s perspective, what it’s like to be in a crew of dirty cops. After that, I wanted to find a way to make it feel like you’d been kidnapped by Michael Dowd and were blasting through the streets of Brooklyn in the late ‘80s and early ’90s at gunpoint, high on blow, and have the experience of what it was like to run with these guys.

You’ve said Dowd was one of the last to agree to an interview. Were you worried you might not have a movie if he didn’t want to be part of it?

Yes, we knew that it was going to live and die on Dowd and it was one of these things where there’s a certain amount of bullshit and manipulation that happens from a filmmaker’s perspective, where I had to tell people, “Look, I’ve got so and so. They’re going to tell their piece, so did you want to tell yours?” That process of being hustled by hustlers and hustling them back one by one led to one another. Eventually, when Dowd signed on board, the first question anybody else we would ask would be, “Who the fuck are you, and did Mikey bless this?” Once I was able to actually say yes, it really opened up the nexus even further in terms of getting to [drug kingpin] Adam Diaz, some of the informants or other members of the crew that I had been able to identify, but not necessarily get to.

When we went to shoot Dowd’s interview, it was like either we’re going to walk out of this and it’ll be a dud or this guy will be riveting. In a weird way, the humor was really a compelling part of it because you’re talking about really dark shit, and yet he routinely made me laugh. I’d be horrified one minute and then laughing out loud the next, and I thought, “Okay, we’ve got something here.”

Is it true you did all your interviews twice, once sitting down and then a second time allowing them to tell the story however they wanted to tell it? If so, did it yield different results?

It was very interesting. What ends up happening is if you’re a print journalist telling the story, if it’s a good story, it’ll play on the page. But with a film, you’re dependent upon the quality of the storytelling and the people who are telling it. I recognized pretty quickly even if it’s a great story, if it’s not well told by the subjects, it’s not going to work, so the process became shooting these insanely comprehensive, multi-day interviews where we would go over every twist and turn and intricacy of the story, so we knew what popped and then get them to either tell it in a more condensed or more detailed way to try to put us, the audience, in the position of experiencing this past-tense story in a very sort of vital and present-tense way.

Interestingly, I think nonfiction filmmaking is evolving to allow, in a cool way, [the approach of] “Okay, now I really need to essentially direct these performances.” There were times that I was fucking screaming at people or having them grab me and throw me down, like, “Put me in the room. Let me see it. How do you do a stick-up? What’s it like?” Being able to give them the opportunity to tell it multiple times, you become collaborators with your subjects in the telling of the story.

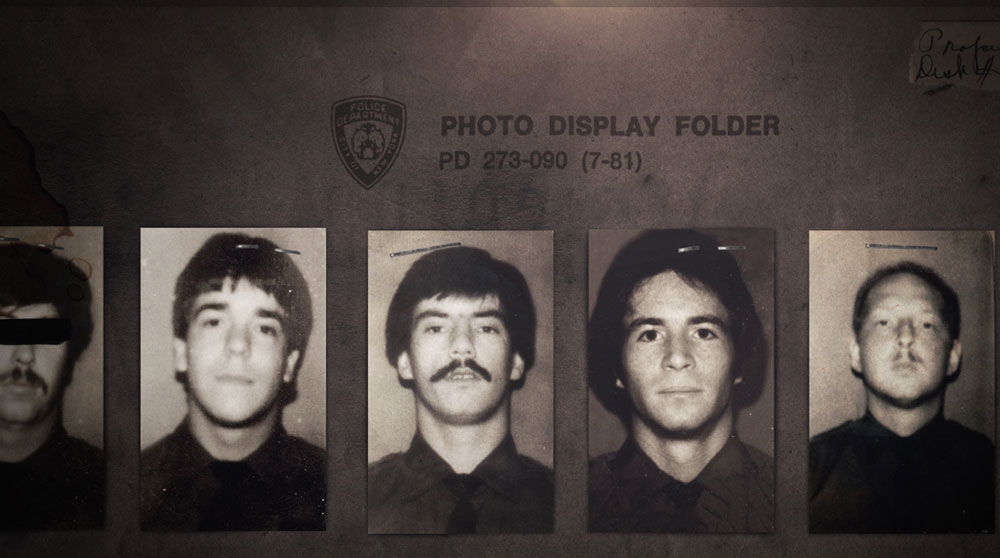

I’ve been talking about all this from the cops’ side so far, but the cooperation and participation of all the good guys [was crucial] — the legit cops, the Southern District of New York US Attorney’s office and the Joe Halls and Mike Trosters [who were Internal Affairs and the DEA], all these guys. This was a defining case for everybody who was involved in it, whether you were a crook, an informant, or a cop, so everyone felt, I think, a very vested interest to tell the story right. We had amazing luck and cooperation where many of these good cops, Joe Hall and Troster, had kept photographs over the years that they had had because they knew this was like a once-in-a-lifetime story.

Then when the Feds investigate somebody, they have the most detailed set of investigative materials — surveillance footage, photos and all that. It’s astonishing what goes into building a case of this scope. Blessedly, the Southern District of New York had retained all of those investigative materials and were willing to share it with us to make sure the story was told well. As soon as we got that stuff, it was like, “This makes the movie.”

You really add something with how you’re able to geographically orient the audience, which appears to have taken quite a bit of effort with the overhead shots and driving through the streets. How did that come about?

It’s like they say, universal stories are often times extremely local in nature, and this was very much the story of a bygone time and place — the bad old days in East New York. So rooting the audience in the experience of this very small and specific yet also epic and mythic geography of the place was really essential. On one hand, it’s a huge period piece [which we wanted to reflect] with aerials, then on the other, it’s the little tiny street corners where the actual bodegas were or the deals or robberies took place. Being able to toggle back and forth between those two really made it feel specific and real.

The Rolling Stones’ “Heartbreaker” plays over the closing credits, which feels like a statement. Why did you want to include that?

That was a brilliant take that Eli had. I remember we first sat down to talk about the movie and what it could be. He’s like, “Dude, this song has literally been playing in my head for 20 years” and I thought, “That is this world.” But it became a very big challenge. It’s the Stones. It’s a very expensive song and you’re just going to have it in the closing credits. At the same time, it perfectly encapsulated that bygone-bad-old-days-cops-in-New-York vibe and the sort of rock-and-roll underbelly of it all, so we really fought tooth and nail. When you go to get a song like that, you’re literally seeking approvals from Keith [Richards] and Mick [Jagger] individually, and they have to see it, sign off, and bless it. When they finally had, it was just like, “Yes, we got it.” It was awesome.

What was the DOC NYC premiere like where you had all of your subjects – clean cops, dirty cops — in the same room?

It was really fascinating. It was literally all those people, many of whom had never seen each other in a long, long time and in a weird way, everyone was like a spoke in the wheel, [with] their own specific take on the story. Suddenly, [I realized] “Wow, I’m the guy at the center of the wheel who’s actually talked to everyone.” As the lights dimmed and the film began, I sunk lower and lower into my seat thinking, “Holy shit! Every single person is going to be pissed off about something.” I just had this horrible [feeling in the] pit of my stomach all throughout the screening, thinking that I was going to have infuriated everyone in some regard or another.

Afterwards, we pulled everybody up onstage and walked outside the theater and went over to a bar. Everybody came — the good guys, the bad guys, the informants, the drug dealers, their families. To a man and woman, every single person came up to me and slapped me on the shoulder and said, “That is exactly what it felt like at the time.” It was so gratifying.

“The Seven Five” will open on May 8th at the IFC Center and the Nitehawk Cinema in New York and will be available on VOD.

Comments 2