When Taghi Amirani and Walter Murch were working on “Coup 53,” the legendary editor of “Apocalypse Now” and “The English Patient” had a seemingly wild idea about shifting the frame in the film when archival material, presented in the once-standard square, 4:3 Academy ratio, could sit on the side of the screen, rather than occupying the middle as it often does traditionally in contemporary films.

“He started doing that and in some sequences, it almost becomes a two-hander where it’s opposite sides of the screen, the archive jumps from one side of the screen to another, creating a dynamic between the faces talking to each other,” marvels Amirani. “That was Walter’s idea, shifting it to one side because why not? It hasn’t been done. Let’s do it. And then that opened up that black space to the side to put in other information or graphics or even split up the name captions.”

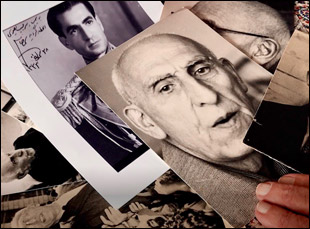

This type of experimentation was naturally exciting to Amirani, who had studied physics at Nottingham University and got to know Murch when he was invited to an early screening of the last documentary he edited, “Particle Fever,” about the discovery of the Higgs Boson to share his perspective. It was also a desire to challenge commonly accepted beliefs that had brought the two together to make “Coup 53,” which uncovers new details about the 1953 Iranian coup d’état that ousted Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh from office. While it’s common knowledge that M:I6 and the CIA helped orchestrate the overthrow of the democratically elected Mossadegh, who had irked the foreign petrol giant BP with plans to nationalize the oil industry, the extent of their involvement is fully brought to light when Amirani revisits a 1985 TV documentary “End of Empire” to find that key testimony of a former high-level M:I6 agent named Norman Darbyshire never made it to air.

Comparing transcripts to raw footage from the program he’s able to retrieve in addition to interviews he conducts himself over the course of nearly a decade, Amirani unravels a mystery that illuminates the naked economic interests of the U.S. and England that prevented Iran from establishing a sustainable democracy, when Prime Minister Mossadegh’s ouster strengthened the rule of the Shah, and have shaped its relationship to the rest of the world ever since. As a result, it would seem that market forces have been trying to suppress “Coup 53,” which was well-received when it premiered last year at the Telluride and London Film Festivals and has subsequently had a surprisingly quiet release thus far, given its pedigree and compelling subject matter. That’s something Amirani hopes to change that this week with a virtual premiere on August 19th, followed by a Q & A on August 20th in which he and Murch will take questions, and shortly before the online event, he spoke about how he found himself in the middle of the kind of investigative thriller you’d be more likely to see Robert Redford in, bringing the events around the coup into the present so vividly with inventive editing and exquisite animation, and why he could be thankful that Ralph Fiennes happened to be starring in a National Theatre production of “Anthony and Cleopatra” right down the road from where the film was being made.

You’re absolutely right. It has been with me all my life and it’s a subject that Iranians have been carrying with them for the last nearly 67 years, so it’s deeply embedded in the psyche. In a way, the subject chose me rather than me choosing it.

Did you know you’d have such a big onscreen role? You become a detective.

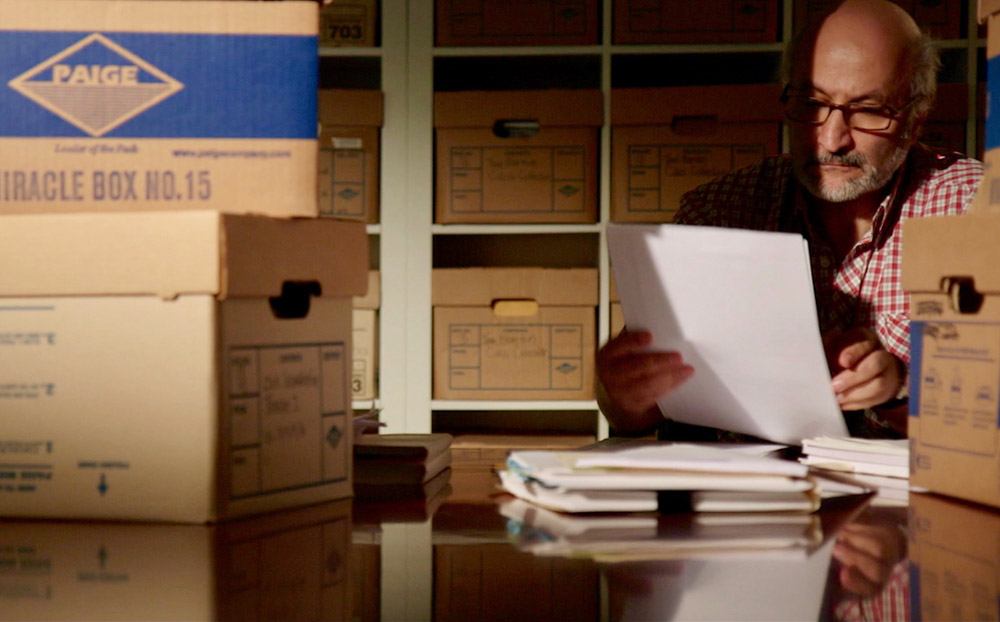

The investigative thriller style wasn’t part of the initial plan, and the reason the took so long and the structure evolved was that nobody wanted to fund this film. We kept shutting down because we couldn’t raise the money. No studio, no funding institution or grants came to us, so I had to raise the money dollar by dollar from donations, mostly from lovely people in the Bay Area, which meant we had time. Every time we ran out, we had time to research and read through the archive and make new connections, so [my onscreen role] came out of putting the research out front because it became a real find. And I didn’t think it would take 10 years. It was never part of my plan that it would take 10 years, that it would become such a monumental colossus of a project involving seven countries, involving a huge cast of interviews and characters and archive material.

I never dreamt I was going to get the great Walter Murch to work on the film with me for four years, which is astounding, and and as Walter says, he had to cut almost twice as much as he had to on “Apocalypse Now.” [laughs] The way I make films, I don’t have a preconceived idea. I have a notion, something I have to get off my chest or something I’m curious about and then let the story evolve and lead us. We spent a few years pushing this heavy rock up the mountain of trying to get it made and at some point it gathered its own momentum and reached the top and started rolling down and we started chasing after it to keep up with it. We’re still chasing to keep up with it because just like we had no support in making it, we’re getting zero support in distributing it.

When Walter came on in 2015, we still had some more shooting to do, and he moved to London to do this, by the way. I was the sous chef to Walter, the master chef [where] I would gather more footage and prepare it and give it to him, so we were filming right throughout the editing. A lot of people will see when they see the film the thriller element [in how] we make incredible discoveries that twist and turn the story, and we have to think on our feet. We were being wrong footed by the unfolding narrative, so hopefully the audience will feel that and we made the film as we went along. As Walter says with documentaries, editing is the writing of the film and you write the screenplay backwards so it was very, very much a collaboration — and Walter is the co-writer and editor of this film — as this film took us on this crazy, wild ride.

We were very much lifting the lid to see what was happening during the making of and of course, we shoot a lot more than we could put into the film. The first assembly of this film was over eight hours. And Walter Murch’s assemblies, by the way, are beautifully cut. They’re not thrown together. He even mixes the sound and the music. At one point in 2018, we sat down and watched the eight-hour epic and we thought, “What are we doing here? Are we doing an eight one-hour [episode] Netflix series? Are we doing four two hours?” Because it has drama, there are even in-built cliffhangers in there and we did deliberate for about two or three weeks – what are we going to do? So out of eight hours, a lot of stuff had to come out and for every minute of amazing stuff that’s in the film, there’s 10 minutes of amazing stuff that’s not in the film.

What’s in there is pretty impressive. What was it like to get your hands on the raw outtakes from the “End of Empire” series?

There are scenes in the film which might take about two minutes, but most of those would’ve been the result of three or four years of negotiations and back-and-forth. “End of Empire” took a long time to find and get access to because until we got permission to get those cans of film, they hadn’t been touched by anybody for like 34 years. We were the first people to actually get it and part of the deal was let us digitize and give it to you so you can preserve it in digital form, so there was a real thrill in getting stuff that hadn’t been seen and sat in a box somewhere for forever or had never seen the light of day.

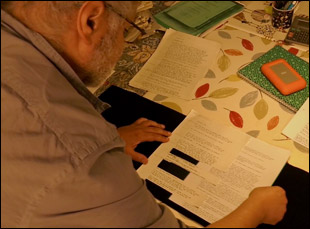

The critical turning point which happened pretty late in the day. We started in 2009, and I think it was 2016, when we found finding that transcript [of the “End of Empire” series], and that cut-up transcript was like the flash bulb moment, like “Wow, here you are, trying to tell the story of the coup in your country that changed the fate of a nation” and has had repercussions that we are experiencing even right now as we speak, and you find [Darbyshire], the man who says he ran that coup. He masterminded it, he directed it, he knew Iran inside out. These are his words and you find that and you get this incredible thrill.

Of course, the challenge is how do you bring those words on the transcript to life. To his credit, it was Walter’s idea to bring the amazing Ralph Fiennes in. They knew each other [from] working with each other on “The English Patient,” and one day we were coming back from lunch in the cutting room when we were grappling with how do we do this transcript. We didn’t want to do just voiceover and text on the screen, and suddenly Walter said, “What about Ralph?” At that stage, the idea was that Ralph would come in and read the words and we’d just record his voice, but a few days later, he was like, “Wait, why don’t we just film him being the guy? And not impersonate him.” He’s doing a really incredibly unique thing with that performance. He’s being an avatar. He’s embodying the spirit of Darbyshire, so the turning point in the film was finding the Darbyshire transcript.

Animation was my brother’s idea. Amir Amirani, who made an incredible film about the 2003 global protest against the Iraq War that took him nine years, “We Are Many” [which] is also hitting America in September. We do fun subjects. [laughs] So he says, “You’re dealing with oil. Oil is the story. What about oil painting animation?” There weren’t a lot of iPhones those days [of the coup]. People weren’t capturing stuff on the streets. So how do you bring that to life? One thing led to another when we were introduced to the amazing animator Martyn Pick, who’s incredible because of the handprinted look of his animation, but I had never worked with an animator and was scared of [them] because they’re into precision [where everything is specific to] seconds and frames, and I was thinking, I’m a documentary maker [where] nothing is planned. But it was amazing.

What’s it like to bring this out into the world?

It’s a real exciting and nerve-wracking adventure. We are very excited to hear and see audience reactions. We had an amazing, spectacular premiere at Telluride, the jewel in the crown of festivals. Incredible write-ups, more festivals, some nominations, a couple of awards, but we are putting the film out ourselves to show distributors this is a film that people want to see. Audiences have been going crazy — I have footage of every single preview screening and audio recording of audiences gasping in packed houses, which is very, very satisfying for a filmmaker with Walter and I putting so much time into it. And there’s a possible follow-up to this story with Darbyshire. We’ve discovered incredible new stuff since the film has come out, which is under wraps, but has huge dramatic potential. It really turns the whole spy story on its head as a dramatic follow-up, so there are things bubbling.

“Coup 53” will screen virtually on August 19th in partnership with venues across the US, Canada, UK and Ireland. A full list of venues is here.