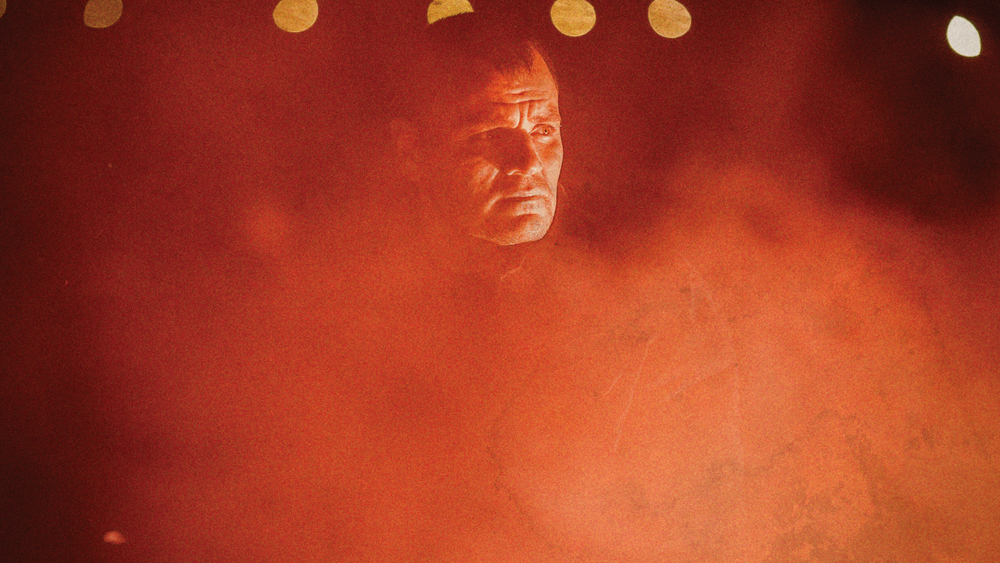

“Today, I must be a pastor,” says the man known as Crocodile Gennadiy, shaking his head as he puts on a clerical collar in the documentary that bears his name. “So many different jobs.”

Not that Gennadiy Mokhnenko considers this a burden. The same broad shoulders that make him remark later he’d make a good fit for the Secret Service are also what presumably give him the confidence to carry an entire community on his back as he does in Mariupol, a city in Southeast Ukraine, where the fall of the Soviet Union left thousands of children homeless, susceptible to the lure of drugs, the spread of HIV and making money through prostitution. With little government infrastructure to rebuild the community, Gennadiy spent 2000s laying the foundation for an organization named Pilgrim, a children’s rehab center that has become the largest in the former Soviet Union, providing detox and security to those that enter its doors.

How they get there, however, is what makes director Steve Hoover’s documentary “Almost Holy” so compelling, as it joins Gennadiy in patrolling the streets for those in need of help, whether it’s an abused wife who’s been kicked to the curb, a young deaf woman who’s been sexually assaulted or running down a pharmacy that’s been illegally selling codeine-laced prescription meds to kids. Like his previous “Blood Brother,” which tracked his American best friend’s life-changing journey to India where he found purpose as a caregiver for children with HIV, Hoover once again finds a way to tell the story of an unlikely humanitarian in an unexpected way, making a film as dynamic and action-driven as its main subject who is trying to forge stability as his country comes under attack from Russia.

Shortly after the film premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, Hoover and Yourd spoke about following Gennadiy into the breach, filming without knowing what was being said and how its New York debut brought them closer to their subject.

Both your features so far have been about philanthropy, though from a far different angle than most take. Is that’s something that’s actually important to you?

Steve Hoover: It’s interesting because both films are obviously different. One was a personal film about my best friend and really with this Gennadiy story, it fell in our lap. Danny and a handful of guys from our production team were commissioned to do a piece in Ukraine. While they were working on that piece, they met Gennadiy and basically detoured from the project to focus specifically on his work. At the time, we were looking for our next feature and they came back from the trip, raving about Gennadiy, his work, and how much of a strong character he was, and initially, I was a little bit hesitant because I didn’t want to develop some pigeonhole for myself [as a certain type of filmmaker], but I was just so compelled by Gennadiy, his actions, the work, and the post-Soviet atmosphere of Ukraine.

It’s somewhat coincidental because “Blood Brother” became philanthropy. It was set up to just be a story, but it became more cause-driven. We were able to do a lot of great things and raise money, but with “Gennadiy,” [we started out thinking] it was more of a portrait. It doesn’t have a cause behind it.”

From that early shoot, did you have any idea what you guys were getting into?

Steve Hoover: I had no idea because I didn’t go on the first trip, but when the [other members of the production team] came back talking about it, they had a sense of what the story was because Gennadiy’s a storyteller. He retells his past, and painted a picture of what life was like there, but we didn’t really have all these details, so I thought it was one thing walking into it, and when we got there, the world revealed itself that some of what we thought was the story was actually the past, so we were excited to see, “Okay, well, what is happening now? What is the story now?”

Danny Yourd: Also, when we first started out, there wasn’t really even any whispers of conflict, so over that span of a year-and-a-half, things just started to escalate and that obviously played into Gennadiy’s life as well.

From what I gather, the majority of the film was shot before the invasion of Crimea. Did the late occurrence of that reshape the story you wanted to tell?

Steve Hoover: It definitely had a big impact because of how much it affected everybody’s life. To me, Gennadiy was a window into a reason that the conflict is happening. It definitely shaped things.

Danny Yourd: It’s still shaping things.

Steve Hoover: Yeah, it’s still shaping his life and everybody’s life. Gennadiy had been working for years to do, in his mind, what he felt he needed to do to make Ukraine and his city a better place and that all was threatened by powers that were really outside of his control and became his greater adversary.

There are a couple things that help you frame the film – a speech he gives at a women’s prison ministry and the crocodile cartoon that gives him his nickname. How did they end up giving definition to the story?

Steve Hoover: There were a lot of great, organic things that happened and this is just one of those things where you don’t know what’s happening, so we did our best to observe. We tried to figure out what the story was, but toward the end of that first trip [we took to Ukraine], Gennadiy had been talking about this prison ministry because [his group] goes into these prisons. His whole mindset now is that since he cleaned the streets of Mariupol with the kids, so to speak, he’s [moving more towards] prevention. Because we said, “We want to see your day-to-day life,” he wanted to show us, Hey, this is something we do,” going into the prisons and trying to help the women [ease back into society] when they get released. Going into the homes, it gets more gray. So [the women’s ministry] does a big event every month at the women’s prison where they put on a little concert and then they’ll give a couple speeches.

We went into every situation with at least two cameras rolling the whole time for content. But the aesthetics of the prison were so fascinating to me. It was all the bright, beautiful blue colors. It was the only place in Ukraine where I really saw these vibrant colors. So we just had all of our cameras – four – rolling the whole time on his speech, and I just said, “Let’s just get the whole thing because we don’t know what he’s going to say.” I didn’t really know [what he said] until we translated it in post [production], but it was really fascinating because he basically walked through a lot of what he had been doing the past month to the women to try to illustrate these different points. It became this amazing thread throughout the film to help explain things, and I needed that. I had hours of interviews with him, but decided not to use pretty much any of it, with the exception of a few moments because I wanted something more organic.

Then the Soviet cartoon [was because] he kept introducing himself to children as “Pastor Crocodile.” It just kept coming up, and I didn’t know about “Cheburashka and Friends,” the Soviet cartoon, so I just asked [him], “What is this?” and he pulled out his computer and showed us, breaking it down. I saw these parallels between him and Shapoklyak, the villain, [and the issue of child homelessness he was addressing].The crocodile was pulling kids out of the sewer, so I could see why maybe he adapted that narrative to himself. When I finally went back to the States and we were translating footage and editing, I watched all of the crocodile cartoon and it helped to fill in some blanks that explain Gennadiy’s world or his mindset that we may not get [because] you see how ingrained it might be because this is what Gennadiy watched as a child. That was really fascinating to me, and I really liked the idea of repurposing Soviet propaganda or revolutionary themes and songs into the film for the new revolution.

There’s obviously a beauty to what Gennadiy does, but how he gets there isn’t always pretty and I felt there was a great muscularity to the filmmaking, but at the same time it allows for a certain elegance. Was the film’s style informed by who Gennadiy is?

Steve Hoover: We all felt going into Ukraine, going into Mariupol, just with the whole Soviet architecture and colors – it was inspiring in that darker way, and I connected with that. Gennadiy is a product of that world, imposing with strong features, so it all worked together to inspire the overall look and feel for the film.

You do seem to have a visual signature – I don’t know the technical term, but there are always shots that have a deep focus where the rest of the frame fades away…

Danny Yourd: The tilt-shift. Those were specific lenses…it just so happened that prior to the shoot, our DP had a shoot where he was using tilt-shift lenses. They’re just a stylistic choice of lens, and we literally just move the lens and it’s like selective focus.

Steve Hoover: It came in handy. A lot of times that technique will be used to almost make cities look like miniatures. But the first time you see a Lenin statue, it has tilt-shift – he’s more in the background, there’s bikes going by, and just the presence of the statue represents a lot of Soviet history. Lenin wasn’t really a big deal at that point, compared to how much that is tied in now. There’s also a scene where Gennadiy’s talking about his parents at his desk, and we have the tilt-shift and it’s like the smallest he looks in the film because he’s going back in time to this very vulnerable place. Later in the film, when we see the Lenin statue again, it’s the low-angle and all of a sudden, it’s a bigger deal because of how much it’s affecting the conflict and becoming a piece of the argument. We used a lot of different in-camera tricks like that lens to try to stylistically tell the story without words.

Since you already wrote such an eloquent piece for Vice about your terrifying days of shooting the invasion, there’s no need to ask about the craziest experience you had making this, but throughout the film you’re following Gennadiy into wild and potentially dangerous situations – I’m thinking of when he rescues the deaf girl Luba from a likely abuser, in particular. Were there days where you couldn’t believe where you were?

Steve Hoover: Because I don’t speak Russian, the whole time, there was a lot of confusion. Going into Sasha’s place where Luba was, I was a little frightened and just very, very confused. The translations that I was being given were very broken [English], and I just couldn’t make sense of it. Like, “Wait. We’re in this village. These women are prostitutes? What happened to this girl’s father?” “Oh, he hung himself right here.” These details were outside of my concept of reality. I just haven’t experienced those things, so it was really difficult to process. A lot of it didn’t make total sense until we got back, translated everything, and began to find the story, which was a really exciting process because things happened, like the Wikipedia call [where Gennadiy sees updates that he believes misrepresent him by saying he’s driven by seeking fame]. We were in the office for that. We’re filming it just because we filmed everything, but we had no idea what was going on in that call until we get back to Pittsburgh months later and translate it. Then we found this incredible parallel with the cartoon. A lot of it was just we didn’t know where we were going or what would happen…

Danny Yourd: We just had to trust.

Steve Hoover: Yeah, and that’s just his life, you know? He gets calls or gets asked to do something. Somebody shows up on his doorstep, and he just rolls with the punches.

Would you actually send footage home to America while you were shooting or was your whole team over in Ukraine?

Danny Yourd: The first trip we went without Steve was just four days. We had a job that we had to do, but we sidetracked a little bit just to get to know Gennadiy. But the bulk of the [primary] trip, we were all there. We have a pretty nimble crew of five people. Then the last trip that was cut short, but we had added one more person who was our translator from here. But we travel with everything back and forth.

Steve Hoover: We were able to break off a lot because we had so many cameras and we just wanted to document everything. What was fascinating to me was the disconnect of the people knowing that we don’t understand them gave them this comfortability to be more vulnerable with us there. That was really something to me because you experience it in day-to-day life where you might be sitting by a couple who’s speaking a language they assume you don’t understand, so they’re much more explicit in the things they’re saying. That came in very handy for all these situations we found ourselves in.

What was the premiere like for you?

Steve Hoover: Exciting. I was definitely nervous. I spent a year editing the film in the dark room, a lot of time with the translator. As the story in Ukraine was developing and things were falling apart, you spend so much time with something, you don’t know how it’s going to be received, even if you feel good about it, so it was definitely an exciting night. To have Gennadiy there was interesting because I sat by him and in a lot of ways, because he’s not in my life, he almost became fictional to me. The things I was looking at and the way we shot it, it started to feel like that because I was so distant from it. But to sit there with him and watch it, no way it was fictional. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see him react or at certain scenes, I could see him cry. It was an interesting experience. And to be able to have him there to answer questions for people was great because he’s still living there and living this life. It was a good night.

“Almost Holy” will be released on May 20th in Los Angeles at the Sundance Sunset 5 and New York at the Village East Cinema. A full list of theaters and dates is here.