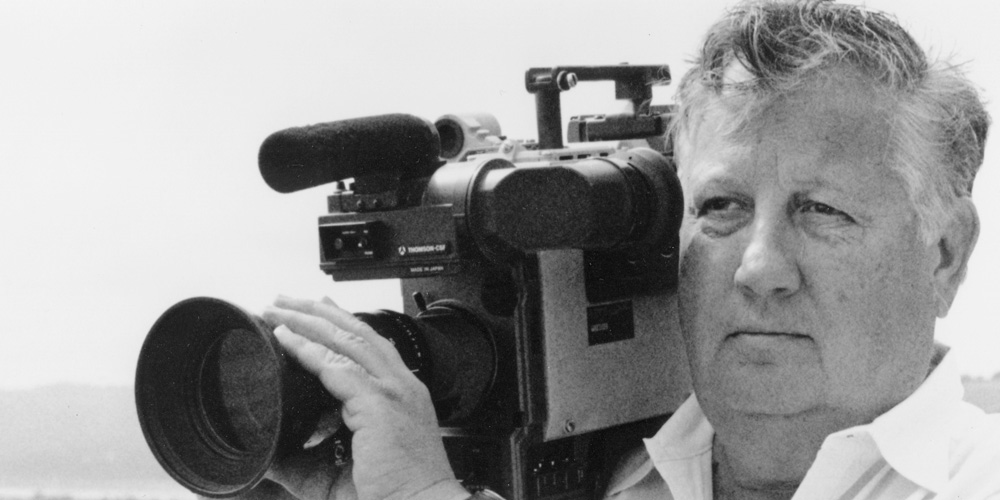

Arguably the godfather of modern documentary filmmaking, Robert Drew passed away today at the age of 90 at his home in Connecticut. In April 2008, I had the privilege of speaking to Drew in advance of the Tribeca Film Festival premiere of “A President to Remember: In the Company of John F. Kennedy,” a film culled from the footage he collected with Albert Maysles, Terrence McCartney Filgate and D.A. Pennebaker, who were provided with unusually wide-ranging access to the 35th President. In honor of this great man’s passing, here is that interview in which Drew reflects on how his legacy became tied to Kennedy’s and how covered politics had changed since he promised the President that if he allowed him to film him as a candidate for five days and nights during his campaign, which provided the basis for the groundbreaking “Primary” in 1963, he could create “A new form of reporting, a new form of history.”

If there’s any truth to the idea that what’s old can become new again, Robert Drew’s “A President to Remember: In the Company of John F. Kennedy” is a prime example. Free of the pressure to film sound bites and be caught up in a campaign’s spin room, Drew simply let the camera roll during the campaign and all-too-brief presidency of John F. Kennedy, creating an influential group of documentaries between 1960 and 1963: “Primary,” “Adventures on the New Frontier,” “Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment” and “Faces of November.”

With an assemblage of filmmakers and journalists from his days as an editor at Life magazine (including Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker and Albert Maysles) by his side, Drew pioneered the practice of cinema verite on what now seems like the least likely of subjects — the president. While Drew’s four films on the Kennedy Administration have been long available on DVD, “A President to Remember” is a bit of a CliffsNotes for the uninitiated, weaving together fly-on-the-wall footage from Kennedy’s early days on the campaign trail to his invasion of Cuba and his untimely death, with narration from Alec Baldwin tying everything together. But what sets “A President to Remember” apart from being just a greatest hits collection is how innovative Drew’s approach to filmmaking still seems (aided by the eternally fresh-faced Kennedy), especially when compared to the coverage of the current election cycle. On the eve of the film’s premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, Drew discussed why Kennedy was such an appealing subject and why, with no false modesty, all his films are masterpieces. (No disagreement here.)

How did this film come about?

I was struck by the fact that a number of generations have gone by since Kennedy’s death, which means that a number of generations of people never knew him or weren’t around when he was alive. The memory fades fast. At the same time, we’ve had a series of presidents and vice presidents who were quite different than Kennedy and some people feel badly about that and I had all this wonderful footage. I wanted to make a film that would tell people what it was like when we had a man who was generally admired in this country, 70% admired, and generally heralded around the world. I had a feeling that the country really needs a picture of itself at its best and people need to have hope and feeling that we have the right stuff, and so I thought if I made a film that showed this man the way he is, it might help establish a better feeling about ourselves.

What was it like for you personally to revisit the material and editing it together?

I’ll tell you I was stunned. I thought I had all this stuff in my mind already, but that man’s sense of humor and his wit kept me rolling in the aisles, especially the stuff which I didn’t shoot of his press conferences. He had a way of answering a hostile conference question — everybody would laugh, but he wouldn’t. Then he would. [laughs] And there are many other parts of the film where his decency and sense of honor and good thinking and good humor all came through — early on in the film, he responds to questions about his Catholicism and in the middle of it, he breaks into a laugh. And he’s quite serious. He doesn’t want to break into a laugh, but I have a feeling we’re seeing the man in a new way. Even though we might’ve seen some of these things before, being able to put them together like this moved me.

Had it long been an idea of yours to put these films together in some form?

Yes, but it had been back in the back of my mind. I’ll tell you, George W. Bush gave me a real impulse.

Did you have to add footage to what you previously had?

Oh, yeah. It turned out that when I wanted to make a Kennedy film, not just [about] getting elected, not just about moving into the White House, not just about dying, but when I wanted to put all that together, I wanted material that I hadn’t shot, so I looked through all the Kennedy material that exists and selected items that would help connect the pieces I had.

Does it surprise you how fresh this still feels nearly 50 years later?

Yes, it did. It’s funny — when I’m editing, I’m usually a very serious guy and it’s usually a painful process for me, but in this film, I found myself laughing here and there and admiring here and there and wondering here and there. I was reacting to my own work and other people’s work, but it was more of an enjoyable experience than I’ve ever had editing a film.

You’ve said that Richard Nixon approached you to make a film about his presidency, but that it would have been a disaster. What was it about Kennedy that appealed to you as a filmmaker and what was it about Nixon that didn’t?

I’m going to give you the negative side first — people who are trying to fool you always reveal they’re trying to fool you. I don’t know how they do it — eye movements or word movements or stuttering, whatever — but Nixon simply gave himself away whenever he spoke, whatever he did — not enough not to get elected, but when his people came to me and asked me to make a film like “Primary” on Nixon, I said, “Listen, the worst thing you can do is make a candid film on Nixon.” And they said, “Oh, but he’s changed.” [laughs] I got a big laugh out of that, but I actually did put them in touch with a filmmaker who’d worked for me, knew how to do these things. They did commission a film and they liked it, but I thought it was devastating.

The main thing [with Kennedy] was the story. My job at Life magazine had been finding good stories for good photographers and that meant that some time in the future, something will happen and if we’re there and shooting in the right way with the right photographer, we can get something wonderful or amazing. I was looking for a story to use our first lightweight camera, which only weighed 50 pounds, and I saw the story of this young senator running for president — his own party was against him. Harry Truman, the previous president, was against him. His religion was against him — there had never been a Catholic president. And he was rich and he was campaigning mainly when I first saw him in the Midwest with a bunch of farmers who distrusted eastern people and rich people. So I thought what a wonderful story, and then I went to talk to Kennedy and I was confirmed that he would be a wonderful character.

How do you feel about your own legacy being tied to Kennedy’s?

Well, I considered that every film I made was a masterpiece and I thought that every film I made was worthy of whatever attention it gained, but as the time goes by, and it has — I’m now 84 — it turns out that the subject matter matters too and the subject matter of Kennedy has gained more attention for my films than any genius I could’ve display in editing them or making them. So it’s definitely helped shape my career in the sense that it helped shape the backing I could get for making other films.

How do you feel about how politics are being covered during this current election cycle?

From my standpoint, politics now are impossible to cover. That is, the network nightly news or CNN are about as good as you can get because none of the candidates have the confidence that Kennedy had to make their own decisions and let things happen. Everything is planned and plotted, and for somebody who wants to make candid films about what’s really happening, that’s impossible. You’ve got people looking over your shoulder when you shoot, people looking over your shoulder when you edit, and I would rather bow out than jump into it. If it were possible somehow to find a candidate who could allow the camera to shoot what happens, I would change my opinions, but right now, it’s much too organized to hope that you could shoot candidly.