As filmmakers who themselves encountered how difficult it is to tell stories from their native India regarding poverty and systemic change over the past decade, Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh were naturally blown away by what they had seen unfolding in Uttar Pradesh, a community largely populated by the Dalit, considered amongst the lowest castes in India’s class system. The partners in film and life had been looking to tell the story of an organization led by women, who in such dire conditions were particularly subject to the pain of inequity, and they were inspired by the work of Khabar Lahariya, a newspaper that had put out a print edition every Tuesday since their founding in 2002 and had an exclusively female staff, going well beyond reporting stories to actively drawing the attention of largely indifferent authorities to the plight of those they serve.

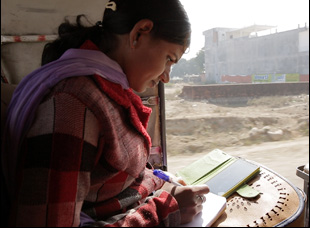

“Writing with Fire,” which generates as many sparks as its title suggests, finds the women at Khabar Lahariya at a crossroads, reconstituting their news operation as a digital-first organization, which would be an adjustment for any outlet, but especially so for one where some reporters don’t even own a phone because of the expense. Still, the women have adapted to plenty already in delivering the news in a such a fraught environment, often viewed with deep suspicion by both the subjects of their stories who wonder if they’ve been bribed or the police who are skeptical about any complaints they hear, and Thomas and Ghosh train their lens on a trio of reporters — Meera, Suneeta and Shyamkali — with varying degrees of experience as they work on stories ranging from irrigation problems to rape and murders in the area that expose larger societal issues that without their spotlight would be easily dismissed or swept under the rug.

Thomas and Ghosh bring their own journalistic rigor to bear on the film, illuminating details of the news gathering process that make it such an admirable pursuit under any circumstances, but made all the more remarkable by what the women overcome on a daily basis, whether they have to constantly reassert their seriousness of intent with skeptical locals or having partners who can only be vaguely supportive of their work as they balance their responsibilities at home with their careers. When Meera has invested over a year in a story about the rising influence of the far-right religious movement Hindu Yuva Vahini, the rewards can be difficult to see from moment to moment, but in the longview taken by the filmmakers over the course of five years, the extraordinary power that lies in such dedication to be a trusted source of information to a community takes hold. The rousing doc has been a favorite on the festival circuit since premiering at Sundance earlier this year where it won both a Special Jury Prize and an Audience Award, and before arriving in theaters this week, Thomas and Ghosh took time away from their recent visit to New York for DOC NYC to talk about making “Writing with Fire,” adjusting to the process of working with the larger canvas of a feature after their previous shorts and how they found themselves in the right place at the right time to make such an arresting film.

Rintu Thomas: That really was the first instinct for us to be in a space where women were in positions of power because we don’t see that enough – stories about women where they are bosses and colleagues and friends. In this case, it was Dalit women who have been completely [made] invisible by the power structures that decide where they should be seen, what they should be saying and how loud their voice should be. So the very first time we met them was in a meeting that Meera was leading — the scene that you saw [in the film] — and the energy in that room was so contagious.

Sushmit Ghosh: The trivia over here is that the first time that they invited us was actually for this meeting that was taking place in Uttar Pradesh, and we live in Delhi, so we took an overnight train and usually on research trips, we don’t take cameras with us but because we were traveling so far, we were like, “Let’s just take the cameras and see what happens.” The first day we met all the women was in this little attic on top of a shop — 23 women in this room and they were all so charged and we started filming. They were not bothered by the presence of a film crew, but they were bothered about this shift to digital and we were luckily in the first day of filming able to pick our three co-characters for the film, so there’s Meera, a natural visionary, calm, composed and thinking about what’s going to happen in the future. There was Suneeta, who was Meera’s foil character, the youngest journalist at that time, extremely ambitious, completely anti-establishment, challenging everybody left, right and center and she had this very lively energy, and then Shyamkali, who seemed very tender and fragile with no idea about what she’s going to do with this shift [to digital], because she had been trained in print all her life.

Rintu Thomas: We were completely taken by their intelligence, their wit and just the lightness of being while doing some really hardcore, serious stuff, so our pitch to them was, “Can we just stay with you for a few months and see where it goes?” They were used to being subjects of short films, so they thought maybe a few weeks max or a month, but by the end of the six or the eight weeks, Meera was like, “What exactly is this? Do you guys have a plan?” And we [told her]. “This is going to take time, but we think this is a story that needs to be told.”

Sushmit Ghosh: Rintu and I had this conversation about the fact that this is the mix for a longer engagement. It can’t be a short. It has to be a feature-length film and there are so many things that are going to happen fundamentally because of the stakes lined up against these women – from a cultural context, from a social context, from a technological context, and an economic context. How are they even going to do this? Is this actually going to work? We decided that the rise or fall of the newspaper was essential going to be a trojan horse for us, and we were going to focus on the lives of these three women and film this story inside out, almost giving the audience a visceral experience of what it means being a Dalit woman journalist in these parts of the country. We had no idea how it would frame out and that’s why we spent nearly five years putting this thing together.

Sushmit Ghosh: That was the question that was essentially focused on this whole idea of trauma. When we started filming with them, we were going into these spaces that were so hostile and dangerous, but also many times extremely loaded with trauma because pretty much every day, there was someone who was murdered or some woman had been raped brutally and we were covering it. We saw our first dead body crime on a Khabar Lahariya shoot and it shook us to the core, so we were just like, “How do you do this on a daily basis?” We asked them this question individually and all of them are like, “This is a part of life over here and you can’t tend to focus on that because you wouldn’t be able to do your work, so our purpose is to report the news and to be able to report it the way it should be. I think they spend less time on the ground emotionally drawing themselves into these stories. It’s very factual. It’s more about what are we doing here today and how do we push this news out because this is news and this is critical.

In terms of just being able to break the boundaries with them vis a vis their own personal lives, everyone took their own time. Meera immediately was like, “Come home, meet my family, hang with them.” And we would spend time with her children and her husband, not filming and essentially that’s how we became such good friends with the family. Suneeta, of course, was a big challenge. During the first year of filming, she was like, “You can film me as a journalist on the ground, but you aren’t coming home,” and [we said], “That totally works for us,” but by the end of the first year, Suneeta being Suneeta saw us filming with Shyamkali and Meera and all the other journalists and going to their homes, that one day she came around and said, “Do you want to come home and have some tea? Spend the night with my family.” And we’re like, “Are you sure?” And she’s like, “Of course, of course. I’d like to introduce you to my parents.” And that night is in the film where you see Suneeta and her father are having this lively banter about marriage and life and education. It was beautiful, and as we spent more time on the ground with the women, they trusted us as professionals and colleagues and that trust evolved into this beautiful friendship and led to intimacy and allowed us as filmmakers access to tell their stories from their perspectives, from within their worlds, which was what our desire was from the beginning.

Rintu Thomas: It was a rollercoaster. On some schedules, we felt, “Oh my God, so much material would go directly into the story because every day, there were so many cases,” and we were filming that. And because we’re also editors, how were we going to put this together was playing at the back of our minds. We couldn’t predict Suneeta’s storyline [though] from day one, she had this dilemma of a modern woman who has had access to education and financial independence, yet feeling the pressure of adhering to social norms and family and honor, which is so relatable for women all across the world. Once we got access to her personal space, in terms of just her mind and how willing she was to be open, that was a big moment for the film because that adds that layer of complexity around her.

The second point was Meera’s longform story with Satyam, the young man who belongs to this Hindu Yuva Vahini group and she had already been interviewing him for a year when we got access. We had to completely let go and say, “Let’s just follow our instinct here” and I think we were very fortunate that he trusted the process and he was forthcoming. We don’t agree with him in any way or his worldview, but we didn’t want him to be some crazy guy who was a hard-liner. We wanted to give him some kind of interiority, so therefore a little bit of his own history comes into the film, [because] it felt like we needed to offer him that space for audiences to understand where this kind of a person comes from. It is also a reflection of a changing India and this film would have been incomplete without that angle. That’s not something that we anticipated, but I’m so glad that happened.

Rintu Thomas: I think the short filmmaker in us came in the way halfway through the process of even production because a short is a completely different way of looking at a story. Beyond the 15-minute mark you have to close in and in our nonfiction work, which we’ve been doing for the past 11 years in India, it’s usually been on stories about people who have done something in the past and the film really talks about that work in a present context, so the visual design of those films is also very different. Here, we made the decision very early on of no interviews. Let’s just be with [subjects] because that energy is just amazing to experience, so this was the first time we were doing observational [documentary exclusively] and learning many things and unlearning many things along the way. Once we got into the rhythm of doing that between the three of us as the crew and the women, it just felt like a flow and the edit was an exercise in patience…

Sushmit Ghosh: The editing tested every fiber of our marriage. [laughs] And by the time we started editing, it was when the pandemic hit, so we had nowhere to go. Even if we wanted to film, it was impossible. India went into this crazy lockdown overnight, so we spent two-and-a-half or three weeks just playing with scene cards. Over four years, every time we’d come back from a shoot schedule, we would edit quick scenes from every day, just to get a sense of what were the stories coming out every day and we consolidated all of that onto these edit cards that we started sticking on the wall. That time spent building the story on paper really helped. Our first assembly was actually five hours and we knew we had a beast on our hands because everything looked compelling, but then it was a matter of just cutting the fat out.

At the 2:15 mark, we were thinking, “This is crazy. We need to get someone in” because you tend to get emotionally attached with the material, especially if you’re directing, producing, shooting, editing your own project. You need an outsider to give that objective perspective, so it’s not about “Oh, this is great from an Indian cultural context and it took me three days to get this scene.” That can be extra fat. So we had Anne Fabini, a German editor who did “Of Fathers and Sons,” very used to working with subtitled films and had no context to caste or all of these cultural conversations in India, but knew what the story was, so she helped us eventually craft the 90-minute piece. We stitched it together and she helped blend the design in very well.

Rintu Thomas: We didn’t know what to expect from a fully virtual year and when you have a film that premieres at Sundance and you can’t be there in person to hear the very first audience responding, it felt very lonely, but what has been beautiful is the response of audiences from across the world. What going virtual has meant is a very different kind of film watching audience has access to festivals and with the power of social media, we get so many messages and tags on Twitter and Instagram and people find Khabar Lahariya and tag them, so that outpouring of love has not stopped. That tells us this has been super-powerful, and I think what people take out of the film is this experience of getting inspired by women who have nothing going for them and then reflecting back on the deeply fractured world where we approach it with a lot of cynicism. The film gives a lot of strong hope – not the nice, vanilla kind of hope, but the hope that if Meera can do it, I can do it too and the world could be a better place. And the pandemic has been a big reminder of pausing and reflecting on where we are headed. We couldn’t see any of this when the film premiered at Sundance and we were sitting on our sofas alone, but nine months into the whole journey and we [recently] had our first in-person screening at DOC NYC, it has been so satisfying.

“Writing with Fire” opens on November 26th in New York at Film Forum, Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal, in Chicago at the Gene Siskel Film Center and in Austin at the Austin Film Society before expanding on December 3rd. A full list of theaters is here.