Towards the end of “Citizen Ashe,” Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, the widow of the late Arthur Ashe, can be seen combing through the shelves of books that he kept, telling the filmmakers, “His treasures were not his trophies, they were his books” before opening one up to find an inscription she couldn’t recall ever seeing before.

“We shot her for a while for that scene that’s at the end of the film, and she said, ‘I’m constantly finding out about this guy,’” said Rex Miller, who may have had hesitations early in the process of making a film about someone whose life was as well-chronicled as Ashe, one of the 20th century’s greatest athletes, but quickly came to learn there was so much more that had been left uncovered during the making of “Citizen Ashe,” which he co-directed with Sam Pollard.

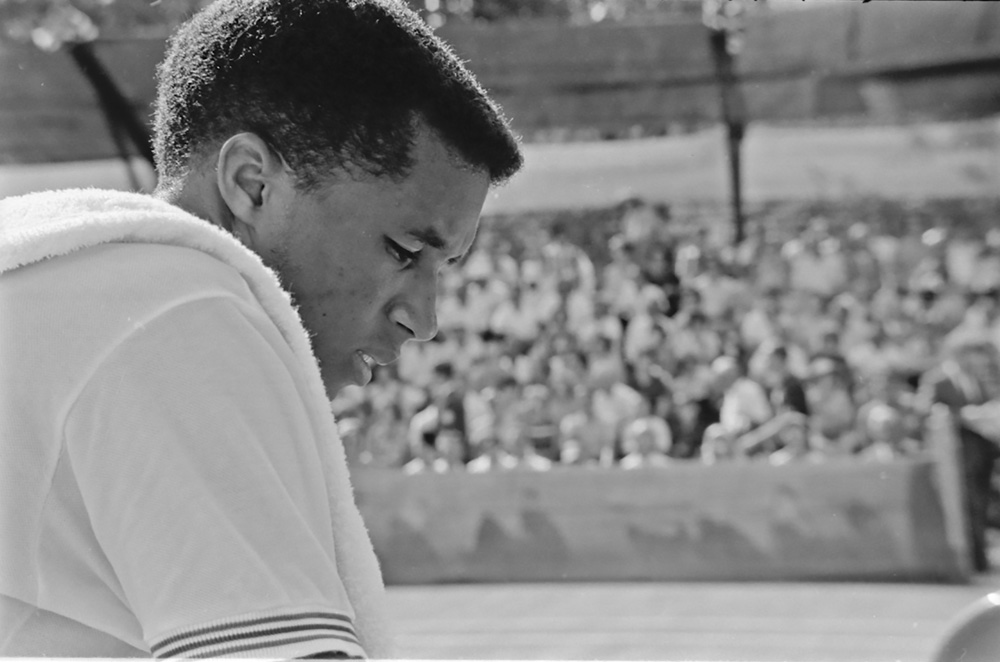

In spite of having the spotlight on him from the time he began playing tennis for UCLA, Ashe’s calm and quiet temperament on the court and off prevented anyone from outside his inner circle from knowing too much about him, keeping thoughts about race relatively close to the vest as he became a trailblazer in the game as the first African American to make the U.S. Davis Cup team and forced to disclose that he had contracted the HIV virus that would ultimately take his life after USA Today had threatened to publish the news before he could announce it himself. Yet Ashe is revealed to come from a family of great sacrifice — his brother Johnny valiantly volunteered to do a second tour in Vietnam to spare his brother from going when it was clear he was primed for a meaningful career — and as “Citizen Ashe” chronicles with the help of rare photographs and footage as well as audio culled from outtakes from the recording of his autobiography, Arthur withstood intense racism in the sport to prove he could reach the pinnacle of it, using the stature he steadily built to bring attention to issues of civil rights throughout the world, particularly in South Africa where apartheid was in full effect.

Ashe’s ability to methodically expose and exploit the weaknesses in his opponents’ attacks becomes a running theme in “Citizen Ashe,” which benefits greatly from the expertise of having both Miller and Pollard behind the camera, a pair that brings with them the experience of being a talented cinematographer and a high school teammate of John McEnroe, in the case of the former, and the latter being the legendary director behind “MLK/FBI,” “Two Trains Runnin’” and “Eyes on the Prize.” With the galvanizing biography arriving in theaters and available through virtual rentals after premieres at the Telluride, Camden, Chicago and London Film Festivals this fall, Miller spoke about how he seemed destined to make a film about Ashe, creating a film around someone as careful with their words as the iconic tennis star, and how the filmmakers got their hands on so much remarkable archival material.

Yeah, I made “Althea” because my mother, who is a brown-skinned Jamaican woman and good local tennis player in Queens, New York, played Althea Gibson in a match in 1958 at the very restricted Marion Cricket Club outside of Philly, and I have a photograph of those two brown- skinned women in their tennis whites on the grass courts at Marion. When that film came out, I had no desire or plan to make a film about another African American tennis player who overcomes obstacles and has civil rights linkages, but a woman named Linda Zimmerman reached out to me and said, I liked your Althea film, and my father John Zimmerman was a Life Magazine photographer, and he spent a week with Arthur while he was winning the U.S. Open in 1968. And we have 41 rolls of film that nobody’s ever seen before. You should do a film about this.” And at first, I said “no” three times. [laughs] But then she sent me the contact sheets.

As a photojournalist myself, I knew her dad’s name and his work, and I just got intrigued with the opportunity. Then I had to consider the fact that in 1968, I was six years old and I was at the finals match of the U.S. Open, so I had a little bit of a personal link to Arthur. I played junior tennis in the East and college tennis at Colgate — I’ve taught tennis on and off my whole adult life – and my kids played tennis, so we just started down that road of this film. But what really spurred on was Arthur’s widow Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, coming on board and saying, “Yes, you can go make this film. I’ll give you my blessing and help you out as best I can.” And this film couldn’t have been made without her and Arthur’s brother Johnny, so it’s been an honor to make this film with their support.

He led such a sprawling life, how did this find its shape?

The original goal was to have it done in time for the 2018 U.S. Open, which was the 50th anniversary, so there was a lot of time and energy spent just on 1968, and at one point there was talk about making the whole film set within 1968. But then how can you make a definitive documentary about Arthur Ashe and not cover going to South Africa and winning Wimbledon? For a while, we even tried to stay away from [the part of his life] contracting AIDS and being outed and starting an AIDS foundation, but we had to touch on that as well, so it grew bigger.

My wonderful co-director Sam Pollard’s biggest talent was finding the throughline [where] we’d feel the most emotional resonance rather than have everything in the picture. Being a tennis guy, there were tennis matches that I thought were important, both because he won, but sometimes they reflected something bigger than just tennis like when he was representing his country overseas, so it was quite an endeavor to take on all this material. We probably had 150 hours of [footage] plus thousands of photographs [in addition to] the 30 hours of audio tapes and 30 interviews that we did, and then the archival interviews, it was a lot of material.

That was something that in the first third of this project was lacking, how are we going to find the emotion in this story. Arthur, in all his media appearances, is very flat and a bit non-emotional. He’s the same on the tennis court – he was not a rock thrower, he was not Muhammad Ali. And then I had the good fortune to find about a thousand pages of transcripts in Arthur’s personal papers at the Schaumburg Center; where Jeanne had given all of his papers, and we reached out to Arnold Rampersad, an author and a professor at Stanford who conducted those interviews. Along with Arthur, he wrote his autobiography “Days of Grace,” so we reached out and he said, “I have no idea if I have those tapes, but I’ll go look in my attic.” And he called us a few days later and he said, “I just found a shoebox with 30 microcassettes in them of Arthur talking to me, would you like to listen?”

From there, it became a whole different film, one where we were really going for this internal dialogue from Arthur Ashe as to what he was feeling. Whether it was about Emmett Till’s murder or not being an activist when college students were getting their heads beat in at the lunch counter sit-ins to what he was experiencing at the most pressure filled moments of his tennis career, or what he thought about Nelson Mandela or Jimmy Connors or the death of his mother. It’s one thing to just put those in there as biographical beats, but it’s another thing to have him expressing what he feels about it.

You’ve got those contemporary scenes upfront regarding athlete activism, which provides a great frame for the film. When so much was going on as you were editing, was it actually in mind as you were putting this together?

I say, yes. We never knew quite how, [because] we looked at Arthur as the person who all of these outspoken athletes — LeBron [James], Naomi Osaka, Serena [Williams] and her activism — really stand on his shoulders. Arthur was one of the first to really be outspoken along with our other iconic heroes Bill Russell and Muhammad Ali and Tommie Smith and John Carlos and we even have Jesse Owens and Jack Johnson, who were activists in their own way, in there and we can go down that whole rabbit hole, so it was always how to find Arthur’s place in the grand scheme of athlete activism, but it was always a goal to link Arthur to the other activists.

And Arthur’s mode of activism didn’t always sit well with people. His approach was non-confrontational, bringing everybody to the table — being intellectual and pragmatic, having goals in mind, but bringing everybody to the table. It’s funny [because] with white people, Arthur’s non-confrontational way went very far and was very effective. I’ve heard it so many times at tennis clubs that Arthur is the black man that white people are most comfortable with. “Oh, Arthur Ashe, he’s such a gentleman. Why can’t those other people be more like him?” And there were a lot of folks in the Black Power Movement in the Sixties that thought Arthur wasn’t confrontational enough. He was called Uncle Tom repeatedly, to the point where on “60 Minutes,” he’s saying, “Uncle Tom, I get that a lot.” But he was going to do things his way and for me, his takeaway was you can’t sit on the sidelines and do nothing. You have to get involved, you have to speak your mind, but let it be your words and your thoughts don’t let others influence you.

What it’s like getting this out there at this moment?

It is not easy to make a documentary, and it feels great for Arthur to have this film done. It’s been five years, so having Sam Pollard come on and these great partners that we know haven’t seen him in films that helped get it over the finish line. And I think Jeanne and Johnny Ashe like it, so it’s just a really good feeling.

“Citizen Ashe” opens on December 3rd in New York at the Quad Cinema and will be available on digital. It opens theatrically in Los Angeles on December 10th at the Laemmle Royal.