There have been a number of ways Penny Lane has distinguished herself as a filmmaker over the years, but one of the most remarkable is the lack of cynicism in her work. Always pushing herself formally, one thing that hasn’t changed has been an unshakeable desire to see the good in people. Her breakthrough “Our Nixon” made use of the president’s archive of Super 8 recordings less to indict the men responsible for the Watergate break-in than to reveal the humanity that contextualized their actions, and only she could court controversy by offering empathy for those who sought community online as the medical community debated whether a disease known as Morgellons should be treated as a physical or psychological condition in “The Pain of Others.” She would reveal herself to side with the Satanic Temple when to dig even a little beneath the surface in “Hail Satan” would be to see unlikely defenders of the Constitution and perhaps more provocatively, fans of smooth jazz in “Listening to Kenny G.” Even when she made “Nuts!” about someone of plainly bad intent — the huckster Dr. John Romulus Brinkley, who claimed to have developed a cure for impotence — it asked audiences to consider how easy it was to be taken in by a con artist when the film itself was so seductive.

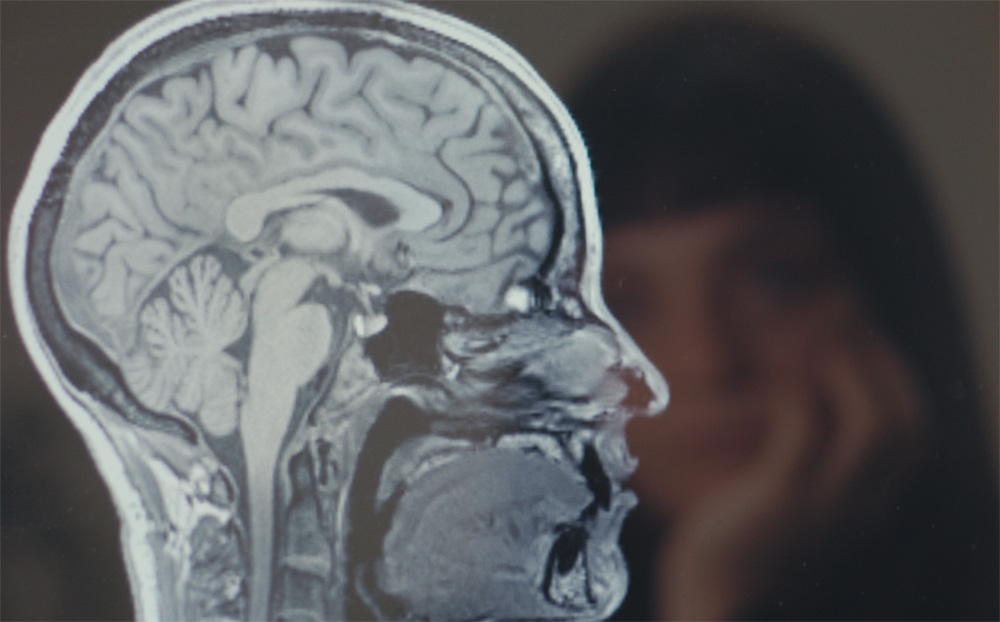

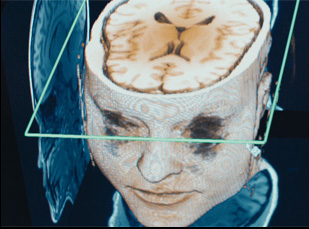

It’s what makes Lane’s latest film “Confessions of a Good Samaritan” get under the skin well before she undergoes surgery to donate one of her kidneys to a stranger. When Lane decided to turn cameras on only a few days before she went under the knife after years of considering such a selfless act, the film is the opposite of self-congratulatory as the filmmaker reflects on a surprisingly lonely experience when logistically the path towards making a donation isn’t exactly easy and society at large has been conditioned to look askance at unnecessary major gestures of kindness.

Leavened with her typical good humor, the film nonetheless sees Lane hardly sparing herself in questioning her motives as she sits for self-examination. Yet for as much uncertainty as the camera picks up from her interviews rife with self-doubt and her contribution towards moral progress as a whole, her command as a director has never been greater as she expresses what ultimately led her to go through with the donation, a culmination of a career so far when it evokes the intimacy of her early shorts about overlooked personal histories, her shrewd use of archival material as a reflection of collective memory in such films as “Our Nixon” and “Hail Satan,” and her disarming way with potentially intimidating subjects on both grand and individual scales, with a rare ability to replace any sense of dread with curiosity and unexpected delight.

After premiering at South By Southwest last year, “Confessions of a Good Samaritan” is now making its way to theaters across the country, arriving in Los Angeles this week after opening recently in New York and we got to witness Lane’s benevolence firsthand when she endured a few more pesky questions about the film, how it took shape in her mind after having such a profound experience and how it came to connect with a larger cultural moment as the world grappled with a pandemic.

It’s a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the structure of the film and the narrative needs of the film gave me a way to process and think through what does this mean? Like you see me struggling a bit in the last third of the film [with the idea of] what does this mean to me? How does it affect my life or how I think of myself or the world? And that was really useful. On the other hand, it was [somewhat] awful not just because I didn’t like want to be on camera, but the needs of a feature-length film are such that you have to mine the experience for drama — that’s what you look for. The dark side and the conflict [because] that’s one of the engines of film to get to the end, so I think if I hadn’t been making the film, it would have been a little easier of an experience, but it wouldn’t have been as deep an experience.

I’ve seen the film a few times now and what’s been interesting is that it’s played differently each time – I think that’s a testament to the depth when there are several movies going on that you can latch onto. How did you crack the structure for it?

It was really complicated and took years and years. The idea of the film changed I don’t know how many times. My first cuts were four hours long. I was really proud when I got it down to three-and-a-half. The topic of transplantation could itself be four other films at least, and as you see in the film, my first shoot really isn’t until about five days before surgery, and what you see is a person who’s really keen and anxious, so I knew [for the film] I had this before surgery/after surgery structure, but it took a long time to figure out what’s the balance between the personal story and the historical, the ethical, the essay-like components. I really didn’t want to be a big part of the movie at first. I really wanted to just be like, “oh, I’ll just come in here and there and guide the viewer.” But then it just became obvious I had to actually create a character [of “Penny”] and create an arc for the character, so that started taking up more and more space. It’s really funny because when I worked on the Kenny G film, I started out thinking it would be a lot more about the critics and then Kenny started taking up more and more space because like it was an interesting character and I wanted represent him accurately.

There was something of a return for me here. It seems like this is the first time any of them are personal films, but of course, that’s not true. Most of my shorts were quite personal, if not extremely personal, and that’s something that I definitely leaned on early in my career, as many artists do for a lot of reasons. You’re starting out and it was really hard for me to be a director and ask people to be part of my film. Then it’s like, “Well, I can always get myself.”

I never thought I would go back to this personal form again, but this experience was similar to “The Abortion Diaries” because I felt like I was having a very profound experience and I wanted to share it with other people. And I knew it would only happen once in my life and I just really felt like, “Oh, this is the time,” even though I had all these confusing senses of embarrassment and shame around the idea of putting myself in this film or making a film about myself. A lot of people have a negative reaction to that idea, and I can’t say that I blame them, like, “What do you think you are? Do you think you’re interesting?” And I actually don’t think I’m interesting, but I am the person having this experience, so here I am. Take it or leave it.

I think that’s beautifully acknowledged in the film, particularly when you let this interview scene with yourself play in the middle – the fact it runs just a little longer than how long you’d expect it might as you wrestle with your feelings about what you’re actually doing and whether it’s benefitting a greater good lets your own discomfort seep in to how the audience might feel. How’d that come about as a centerpiece?

Yeah, I agree with you. It probably feels subtle for a lot of people, but I do think that’s the core of the film and I remember reading Susan Sontag, who wrote the best essay structure moves from a place of unearned confidence through a morass of confusion into a more well-earned sense of nuance. And that’s exactly what I was trying to do with the structure here. What you see ultimately in the structure is Penny before [the surgery] very anxious, but also very confident in her views, like “Everyone should be doing this. If you don’t do this, you’re dumb. Why is everyone acting weird?” Very defiant. But I saw in transplantation this very simple story of moral progress and technological progress intertwined and feeding into one another, so it was both the historical research and the personal experience and going through all of that and trying to articulate it.

But then I found a much more complicated truth, which was really that in real life, there are no miracles and all technological progress comes with some kind of cost or trade off — something more complicated than just “Now everything’s better.” There was no organ crisis until you had transplantation — transplantation actually creates the organ crisis in a way that [because there was no need for organs before]. So I was like, yes, I still believe in progress. Yes, I still think it’s better to have scientific progress than not, but also where we are today in transplant is that we’re probably going to start harvesting kidneys out of pigs pretty soon and as someone who thinks that pigs have some claim to moral consideration, that’s not a straightforward good outcome, so we just keep kicking the can down the road with each with each progression comes another set of moral problems. That was how I left it in the end. I was like, “Okay, I guess it’s a little more complicated than [the Penny you see midway through the film thought]. That’s a good thing. But it’s also difficult to express in a film.

I’m so happy you brought up the score because if I had to name the best thing in the film, the score might be it. I played with a lot of different ideas for the temp score throughout the long process and at some point, I hit upon the theremin as a key sound. I was on Spotify just listening to different theremin music, and I found Carolina Eyck. She is probably the world’s most renowned theremin player and I loved her music and started using a lot of it as temp score. But then [I realized], “This is definitely it,” so I contacted her and asked her if she’d be interested in collaborating and she’s never done a score before, which is the most insane thing. She was so naturally good at scoring that it was bizarre. I’ve never experienced anything like it. She always nailed it the first try. She’s in Germany, so I’ve never even met her in person, but it was an incredible collaboration and I’m definitely going to work with her again.

I know that happens these days a lot anyway, but having to work with some people afar like that brings up the fact you were putting this together in the middle of the pandemic and you’re telling the story of this isolating experience of going through a surgical procedure. Did that feeling seep into the film?

Totally. And there’s no question that this is a pandemic film in a lot of ways. I made the choice not to like overtly reference the pandemic because I didn’t think anyone wanted to talk about it anymore. But I don’t think it would have been the same film if it hadn’t happened. There was a turn to the digital aesthetic, which I think had a lot to do with reality and what was possible at that point, and it was reflecting reality in the sense that there’s so much of the crafting of the character of Penny. Like you wouldn’t know that I have friends in [“Confessions of a Good Samaritan”]. But we’re crafting a character here. We’re not telling the whole story of Penny’s life. We’re telling you like the parts of Penny’s life that are relevant to this story, so I very much emphasized the truth of my feeling of isolation and being single and living alone in a studio apartment during the pandemic. That’s very much part of the film aesthetically and it’s in there thematically and it probably pushed the film in different directions.

It also gave me a sense of moral urgency because I was talking about transplant and kidney disease and then suddenly we were all being asked, what kind of sacrifices we were willing to make, maybe on behalf of an anonymous stranger. I didn’t personally know anyone with an autoimmune disease or who would be especially endangered by COVID, but I still stayed home for two years, pretty much in an attempt to protect the people who were. So suddenly we’re all being asked what kind of sacrifices we were willing to make for others and [the themes of the film] felt a lot more resonant, even though again, none of that’s in the film. It’s all in the background.

You always find out what film you made when you start showing it. It’s always true, and it’s never been more true than for me with this film. I truly did my best to express the truth of what I was feeling and thinking, and at some point we had to just stop, even though I didn’t know if the film was really done. And I really I felt the film was done as soon as I started showing it to people and hearing their responses and being able to see it reflected back to me and others. It’s been really great. The Q&As have been really interesting and powerful — maybe more awkward on a personal level than usual because I have to talk about myself so much more. I’m not in love with that part, but it has been really great and I’m really excited to get to finally share it with more audiences than just the film festival audience.

“Confessions of a Good Samaritan” opens on Los Angeles on July 10th at the Laemmle Royal, July 11th at the Laemmle NoHo 7 and July 12th at the Monica Film Center, July 14th in San Francisco at the Roxie Theater, July 18th in Rochester, NY at the Little Theatre and August 18th at the Tomorrow Theatre in Portland, Oregon.