After a career making narrative films, Nils Gaup might’ve wondered if he would ever see the passion that he could summon from his actors when making his first documentary “Images of a Nordic Drama,” set in the art world. It turns out all he needed to do was say the name Aksel Waldemar Johansson.

“It means so much for [some] to destroy these pictures and it means so much for some to take care of the pictures, so that fight is like the driving force in a [narrative feature] as well as in this documentary, so for me, I wasn’t like doing anything,” says Gaup, on the eve of the film’s premiere at Hot Docs. “It was coming to me like if you have a camera there and you start talking about the art of Aksel Waldemar, you can see in the people’s eyes that they are really engaged and passionate about the art.”

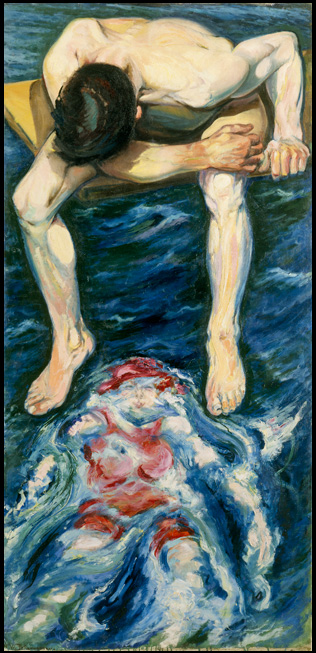

It is easy to see what stirs so much passion in people about Waldemar’s work where the oil paintings drip with emotion, but less so why he isn’t as well known as his Norwegian contemporary Edvard Munch until Gaup profiles Haakon Mehren, the art collector that has devoted the later years of his life to enhancing Waldemar’s reputation. Discovering Waldemar’s work stored in a barn and largely unseen by the public, Mehren’s fervent belief he’s made a major discovery falls on deaf ears at the National National Museum of Norway, where the painter is dismissed as “coarse.” Still, what many local gatekeepers see as amateurish, Gaup believes to be a rebuke to the establishment and begins an arduous process of finding places to exhibit Waldemar abroad where international appreciation might build.

“Images of a Nordic Drama” may start out with Mehren’s quest to put Waldemar on the map, it comes to encompass a far larger struggle within the fine art community where curation can be heavily be influenced by money and power to make or break careers ultimately only comes down to a powerful few. Even though working in nonfiction may appear to be a departure for Gaup, the documentary hearkens back to his very first feature, the Oscar-nominated drama “Pathfinder,” for which he told a story from the point of view of the long-marginalized Sami community and in centering Mehren, he is once again able to reveal how prevailing cultural attitudes have shaped history and left major blind spots that deserve recognition and reevaluation. With “Images of a Nordic Drama” making its debut in Toronto this weekend, Gaup spoke about how he became interested in making a film about Waldemar and the opportunity to present his art to the world, even when so many would like to suppress it, as well as how his commitment to telling the truth found a natural home in nonfiction.

I saw these pictures in Vienna and it touched me in a strange way. [They’re] not nice paintings, the fresh [kind of] paintings that everyone likes in Norway of the fjords and the scenery and all those things. This was a bit provoking and I had the feel that these paintings were about our culture and our life that we don’t want to exhibit. We want to hide that. Those are the kinds of things we don’t want to show and that’s exactly what Waldemar is doing is painting the dark side of society and our life. So I got interested [in Asked Waldemar] and Haakon, the main character in the movie, told me the story of the movie and I thought it was a really fascinating story, but could not be a [narrative] feature movie because it’s so much passion, so much struggling and so many failures and fights going on all the time, it was almost unbelievable.

Also, [this story] got behind the curtains of the Norwegian elite systems and I didn’t know is that it’s almost impossible if you’re an artist to get your art inside museums. You need the nod from this small clique that’s sitting on top and making decisions. If you can do that, you might end up in the National Museum. But if you have enough money, you can get as many paintings as you want inside the National Museum, and that’s a big scandal in Norway because it’s all paid for by by the state, which means by us, the taxpayers, and still the richest person in Norway can buy a room and put his paintings in there.

Was it much of an adjustment to make a documentary when your career up to now has been in narrative fiction?

No, documentary somehow has a same kind of structure — a good story always [does], which is an Aristotlean three-act structure — but it was really interesting to see that the structure and the story came out from nothing, so suddenly, you see well, this is like the structure of a feature movie. And [the story] changed all the time. I shot and edited the movie for five years. It’s a long, long time. And when I would feel I had a story and this is going in the right direction, something happens and kicks the whole thing away and you have to start from scratch again because I’d feel I wasn’t making something that wasn’t truthful [when] something turns up and you have to go with that, so you have to start over and over again all the time. I started out with a nice idea and it ended up as this movie that I could never be sure really what it is.

The art itself is presented in an interesting way throughout. What was it like to figure out?

Yeah, the first time you see all the pictures, it’s in an old barn and this is a reenactment because that [originally] happened in 1990 [when Haakon bought the collection], so we had to recreate the whole scene and suddenly I had a feeling that we were doing an exhibition in a barn because Haakon was telling all the different pictures there and what they looked like. When we did that, we had the presentation of the pictures we were going to use and reuse throughout the story because there’s so many paintings, I can’t show every painting. That would take too long time and the story would stop there, so only the pictures that were in the first exhibition throughout the barn were in the story.

It has an appropriately complex score. What was it like to put music to this?

Yeah, I engaged a very good composer [Kjetil Bjerkstrand] to do the score because I knew he was very into this period and the arts world, and he understands the culture. He’s also somehow a guy that likes to provoke and he engaged Arve Tellefsen, the best violin player that we have in Norway he played in the first exhibition that Askel Waldemar was in in Italy, and I interviewed him [for the film] and asked him, “Do you remember the exhibition?” And he said, “Yes, I do,” so I brought him into the movie and then it turned out that he and the composer were good friends, so we sat together and made a very special score.

At a few points in the film, people talk about how Aksel’s work was meant to be private and for himself – was that actually ever used as an objection against presenting it publicly?

No, I don’t think that was an argument. The arguments were really that we like to present Norway abroad as a nice country and then sending out images that are nice, like PR for the country. These paintings are not nice paintings, [and the thought was] it will somehow destroy the image we are building of Norway as a nice country. But they’re telling the truth, the dark side of Norway that we aren’t very proud of and I think that’s exactly what art should do. Art shouldn’t be a PR system for a country. And Norway is somehow an extremely nationalistic country in a way that we want Norwegian culture to be something nicer than, for instance, Sweden. [laughs]. So there’s competition going on.

Have you felt that responsibility yourself to present that darker side because it seems to be a running theme throughout your work?

Yeah, so much artwork and movies are about the nice things that we are very proud of and I feel that’s a way of trying to be very nationalistic. And I don’t like nationalistic things at all. I like the truth. I believe that all people in the world have a good side and a bad side and we don’t want to talk about the bad things, but the artists have to do that.

“Images of a Nordic Drama” will screen at Hot Docs in Toronto at the Varsity 8 on April 30th at 11:30 am and May 5th at 8:45 pm.