For her latest film “One Fine Morning,” when it came to casting the mother of Sandra (Léa Seydoux), a single mom with the weight of the world on her shoulders as she tends to a young daughter and a father ailing form dementia, Mia Hansen-Løve was imagining someone who could suggest that life might not be that difficult for everyone, acknowledging that fate is a fickle creature and offering a bit of hope for her daughter that there might be more hopeful times ahead.

“I like this contrast between Sandra’s dad who is going down this cruel [path], but at the same time, [life] is going really well for his previous wife because it gives you a more nuanced vision of getting older,” said Hansen-Løve, who would enlist the chic writer/director Nicole Garcia for the part. “I also saw it almost as a little bit of a revenge for ‘Things to Come’ because in [that film], Isabelle Huppert is left by her husband and he’s having a new life and she’s not in despair, but she could be — everybody lets her down and it’s going really bad. It’s the irony of life. It’s never only about one thing. It’s about the variety of life that is the truth to me.”

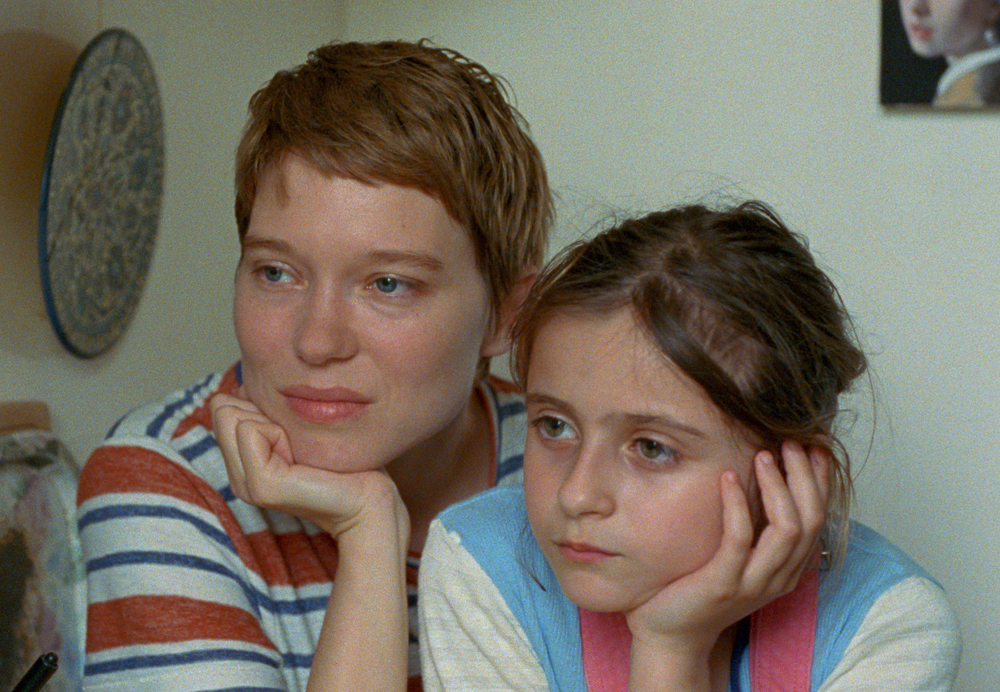

It is the best of times and the worst of times in “One Fine Morning” where Sandra is caught between two worlds, one inside the sterile confines of her apartment and her father Georg’s hospital room as his mental state slowly starts to deteriorate and the glorious escape she finds outside as she spends more time with her daughter Linn (Camille Leban Martins) and Clément (Melvil Poupaud), an old friend who is rarely in town but whose work in astrophysics has brought him back to Paris. Though she is used to translating French for visiting dignitaries in her line of work, Sandra’s personal life requires more and more interpolation as sadness in one realm can be buffered by joy in the other, never entirely moving in one direction when Georg can show flashes of his old self and Clément hasn’t quite extracted himself from what he believes to be a loveless marriage.

Hansen-Løve has made no secret of the fact that the film was inspired by personal experience, something that has been true of so much of her work and she is particularly generous and insightful here, channeling the intensity of caring for a loved one who will never entirely be who they once were while experiencing the exuberance of a new love and though it’s a balancing act for Sandra, Seydoux makes the difficult part look effortless in one of her most magnificent performances to date. On the eve of the film’s U.S. release following its premiere last year at Cannes, the director spoke about what it was like to work with Seydoux and Pascal Greggory, who plays Georg, as well as why she’s invested in becoming familiar with the professional lives of her characters and how her films have started to replace her own memories.

It was a bit like the same with Isabelle Huppert when I did “Things to Come.” I really thought of her while I was writing the film and it helped me because the film was in some ways painful to write and Lea brought me into fiction. I wasn’t trying to find somebody who looked like me or who would be exactly like me. It was more somebody I could connect with as an actress and at the same time emancipate me from my own life. There is also this sadness about Lea, and although she’s [given] very different performances in many films I have admired, [that] sadness about her that moves me and I could feel it’s true and not acted, like something that she carries within her. She, of course, uses it it a very smart way as an actress, but it’s belongs to her and it’s not fake.

I felt I could use that in a way that was going to be different from before because I think she’s been [seen] from a male perspective as very glamorous, always in fancy clothes with desire and distance, and the character of my film was the opposite. She was going to be very simple and down-to-earth and real, so I knew what she could bring to the film, but I thought maybe also the film could bring something to her as an actress. That’s what makes the encounter really interesting, and I thought actually that simplicity may be new for her. I enjoyed having that feeling that there was something new about playing this character that we see in her every day life and not a man’s fantasy.

Something I was struck by was how you move between the scenes in the apartment and the hospital and the outside world – there’s such exuberance once you get out in public. You’re going to naval bases and art museums. Was there a desire to be out there or did the duality of that appeal to you?

Maybe it has to do with my previous film “Bergman Island” as well, the fact that I had just made a film where it was the complete opposite, escaping from Paris. Of course, that reflected on my own life as well, but in a very different way and I was in such a remote place for such a long time when I shot “Bergman Island” that after making it, the next step was to face my life at home and try to understand there were some things about it that I was trying to meditate about and understand. I thought there are topics that I’ve been through that maybe everybody can connect to, but I had to go through with this to move on. There was no other way. That meant shooting in Paris, including in public places that are not so cool or fancy to film, but they’re real life for me. They look how my life has been for a while.

Also there was this idea of [living] nonstop where you go from one duty to another and [for this] certain moment of my life, I try to find meaning to that and what it was, especially simulating a very painful and tragic moment and another that is really the opposite and how that can work together. For instance, how you take the strength to face the tragedy of life from physical love and how that gives you the courage to face that. I thought that was beautiful about life, that life took me and my father in such a cruel way but at the same time gave me other things [to find] the strength to still believe in life. I wanted to try and find the form that was giving the audience the chance to meditate on that.

My father was a translator himself, so I’ve been interested in that job for a long time and I grew up with this idea of not belonging to one culture or one language, but having at least two cultures as part of my culture. I always felt more like a European than French, and because my father grew up in Vienna, but from a Danish father and then he went to France, I have this really variety of roots, like most of us have. I studied German myself and often when I choose a character’s job, I need it to be something I would do myself. Maybe it’s a weakness in a way and I envy the directors who can imagine any job for their characters. For me, I need to have some kind of relationship to that. It also made sense because the film deals a lot with the idea of transmission, so the fact that she would be a translator when so much of her life is also about translating and listening — she listens a lot to her father, and [then] what she was doing in her private life [and how those would be in communication with each other in her life].

[Then with] Melvil Poupaud’s [character] I wouldn’t say it was an accident, but I met somebody who was doing this [astrophysicist] job, somebody I didn’t know and I met and he became a person I talked a lot to. I thought it was very fascinating that although it’s a very modern job, when you see him working at his office, it’s very old fashioned. It doesn’t look that fancy or that high-tech, and I liked this contrast that is against the cliches that films deliver a lot about this kind of work. At the end, it looks like a very literary job and I liked that about it. The fact that I knew somebody who was really doing this allowed me to be very precise in my way of telling about it and I was filming in his actual office. I also liked this idea that it’s a little bit of a romantic job, or at least, it looks romantic from the outside and Sandra is at this point in her life where everything is so harsh, she needed to meet somebody who takes her out of this and opens an imaginary world that’s new for her.

I never made a film with two sisters, so I was interested in doing this and Sarah [Le Picard] is an actress who I like very much and I thought it worked very well to have them both as sisters. But in my films I like to keep some things in the shadows. I want her to be there, but I don’t feel we needed to know that much about her and just feel she is probably facing that situation in a different way. Maybe she doesn’t even live in Paris — we don’t [know] and the film is not interested in her life, but she’s real and a lot of that was thanks to Sarah, who played Isabelle’s daughter in my previous film and she always brings this natural authenticity about her that as soon as she’s there, it makes the character become real.

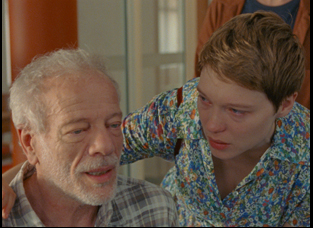

What was it like working with Pascal Greggory on a performance where the character’s health has to be modulated?

I loved it because Pascal was so open and humble and generous with me that he knew that I knew that this really well. It was really fresh for me. And he didn’t know anything about it, so he just trusted me and I could really drive him in “this obscurity,” that’s how he would say it. But very quickly he found the right tone and then he could just follow it. I felt like I could see my own father too well and that was sometimes vertiginous, thanks to his humility and his desire to really disappear within the role. He’s an actor who I wanted to work with for a long time and I just never really had the opportunity, but he’s been in several of Rohmer’s films, a director who I admire a lot and I also enjoy the idea that in Rohmer he’s seen as a very talkative character. He’s very much an intellectual and I thought that could also bring something very interesting to the part because although he can’t speak anymore in my film. But because of his presence and his previous characters [where] language was connected to who he was, [even when] he can’t speak anymore, we feel he’s been an intellectual before. Even people that don’t know about the films of Rohmer could feel that because they feel his sensitivity and his melancholy. It’s really part of who he is and it was very interesting for me to use that, especially in a part that he could not express himself in words really.

Well, I don’t watch them again once they’re done, except if I have to see the last five minutes at a retrospective, but I totally use them as memories. I have such a bad memory and I’ve always had that feeling that time passes so quickly, everything vanishes. It’s really the one fear I grew up with, I don’t know why – it was always so scary and powerful in my life, that fear and I think the reason I started making films is still the same, that didn’t change. To me, it’s about keeping moments of life, although I know they are transformed, I know they are not exactly what life is because it’s with actors, it’s recreated, it’s fiction. But still for me, it’s a way to keep what’s essential, what it’s really about, the feelings, the love …what life is about, I try to keep track of that and when I look at my life, the best way of knowing where I was at is looking at my films. It’s like a diary but in fiction.

“One Fine Morning” opens on January 27th in Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal and New York at the Film Society of Lincoln Center (Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center and Walter Reade Theatre) and Film Forum. It will expand in the following weeks – a full list of theaters and cities is here.