When she was studying journalism before pursuing a career as a filmmaker, Maryam Touzani was always content to let the story come to her, attracted to the profession when it gave her the ability to tell the stories of those who were rarely afforded a proper platform, but enjoying listening to others more than speaking herself.

“Of course, this desire for truth in the films that I make is nourished from journalism because when you’re a journalist, you’re trying to dig and dig and dig and dig for truth,” the writer/director told me recently. “It’s [still] about trying to find the truth of my characters and the story that they’re trying to tell and being able to tell it as sincerely as possible.”

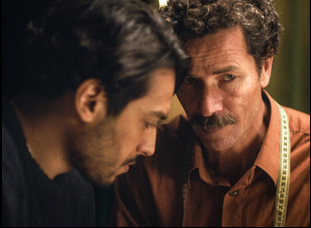

Touzani knows this takes time, at least on screen, if not off when in just two features she’s developed into one of the most distinctive filmmakers in the world, and it’s no wonder that she’s been drawn to stories where process plays a big part in her characters’ lives, first telling of a baker (Lubna Azabal) who takes in a pregnant young woman who rekindles her passion for life in her beguiling debut “Adam” and sitting in with a tailor (Saleh Bakri) of magnificent garments who takes on an assistant (Ayoub Missioui) as his wife (Azabal) starts to succumb to cancer in her sensational second feature “The Blue Caftan.”

Affording patience for those at odds with a world increasingly on the move, the filmmaker allows the richness of their lives to come to the fore, as well as the parts that are often overlooked or kept hidden, which in the case of “The Blue Caftan” involves Bakri’s Halim inching closer and closer to embracing his true sexuality when the marriage he entered into to conform with societal norms appears as if it’s coming to an end. This isn’t to say, however, that Halim and his wife Mina don’t share the deepest of connections in the drama and as resplendent as the dresses that emerge from their shop, Touzani may weave together something even more radiant as she illustrates all the forms that love can take when the couple can see things in one another that they can’t entirely comprehend for themselves. Taking after Halim, who puts his full care and consideration into every stitch, the end result is gripping due to the exquisite lattice work of Touzani and her crew who find tactile expressions of emotion and enshroud one time and again in impossibly intimate spaces.

After premiering at Cannes and embarking on a festival run that has included Toronto and Chicago, where it recently picked up a much-deserved Best Director Prize, “The Blue Caftan” was selected as Morocco’s official entry to this year’s Oscars and upon its opening this week in the U.S., Touzani graciously reflected on nursing the story for it for some time, starting to write the screenplay the same week her first film “Adam” premiered at TIFF in 2019, and how she is able to achieve such a strong feeling of sensuality in her films, as well as why good things come to those who wait.

It all spilled out at 4 or 5 am after some jet lag, but it had been inside me for a while. I had been haunted by this man that I met in the Medina as I was scouting for “Adam,” and I was very, very touched by all the things he wasn’t saying because I felt that there was a whole part of his life that he was obliged to hide. I ran into him as I was scouting, and we sat and spoke, and then I came back and saw him again and there was something very, very powerful and very touching about him. It was his sensitivity and all these things that I felt were not said. When you live in Morocco, it’s a society where being gay is something you don’t talk about. And there are a lot of gay men or women — more men I know of in marriages because they have to keep a certain facade for their society and growing up, I had heard of marriages where the husband was gay, but nobody talked about it.

When I met this man, it took me back to my childhood and there was something very palpable, very tangible, and very violent as well that I felt, and this man was so dignified in the way that he held himself, and there was something so beautiful about him. He had to evolve in this context that was very, very, very conservative and pretend on an everyday basis, so I went down to shoot “Adam,” and when I was in Toronto, the emotion that he had left within me every time resurfaced, so this story had already started to take shape. The characters were already starting to outline themselves somehow and I just started writing because he was there. He just needed to come out.

I thought a lot [also] of what it was to be his wife as well. For me, all that remained inside me was love. If you love somebody, really, what matters when you really love and for me, it’s a film about love, period, and all the different ways of loving because there isn’t only one way of loving. Unfortunately, in certain places, you’re not allowed.

When that was the case, I wondered after working with Lubna Azabal on “Adam” actually gave you a foundation for this when she’s obviously so central to how “Blue Caftan” unfolds?

Working with Lubna in “Adam,” I realized how true she was to the characters that she gave flesh to and that she chose to interpret. She doesn’t do things halfway. She goes all the way she has to go in order to search for her character, and I’m like that as well. I’ll go wherever it takes to try to delve the maximum into my character, so we’re very close in that sense and as I wrote this film, I had Lubna in my mind from the beginning because I knew that together we’d be able to go places with Mina. Mina is a very complex character. She has lived for 25 years and has chosen not to see certain things for the reasons that we know, but out of love, and there are places that she chose not to go to in order to protect her marriage. I knew that was a big emotional journey that Lubna, as an actress, would have to get into in order to explore Mina, but she was the right person for this.

Yes, when you shoot a film like this with very few characters, it’s something that I really enjoy, being able to completely plunge into the characters and into their relationships and be with them as they evolve and into their everyday experience. When you cast for a film like this, every actor or actress has to be responding to their character. They have to feel the truth of that character. It’s not only about acting the part. It’s about understanding who you’re really playing, and then even when you have that, there is a chemistry that has to be between these characters because we’re in a film where there are not a lot of characters. Of course, I didn’t know beforehand, but when I put Lubna and Saleh together, I understood very quickly that this chemistry was possible between them and when you want to be so intimate, there are concessions that you can’t make. It’s either right and truthful and authentic, or it’s not. And if it’s not, you can’t go there in that direction.

It’s the most amazing thing how you’re able to get inside scenes with the camera, and everything feels so tactile and sensual, yet has it been difficult to figure out how to get the apparatus of production out of the way of the actors in telling stories the way you do?

When I shoot, I like to keep a minimum of people on set. Of course, you talk about sensuality and tactility. These are things that are very important for me. Detail is very important for me. For me, all the details help us know these characters better. When you see Halim working on his caftan, the hours he spends, the way he touches his material, the way he does the thread — everything is there also to help us understand further the complexity of this character, and it’s about being able to shoot him and his relationship to the trade in this manner, being able to capture the moments through a glance, all the things that you don’t necessarily put words onto, and finding this closeness to the characters is essential, to be really as intimate as possible with them.

The film is similar to “Adam” in terms of structure where there’s such patience upfront. The story just slowly creeps up on you after you enter the lives of these characters, to the point where you just enjoy being in their world and seeing their routine. Has it been difficult to trust your instincts there?

From the start of writing, I knew the rhythm I wanted to give the story. I knew the pace. And what I wanted above all is that the pace and the rhythm be true to the characters and certain scenes impose their own rhythm. I really believe that we try to go too fast most of the time in general, not only in films, but in life. And I like being able to take my time in certain moments and to experience things fully. That’s the beauty of film is that you can decide to set your camera on certain things that you don’t necessarily see in everyday life, on details that you don’t pay attention to, and be able to give some things a different dimension. And that’s freeing in a sense because it’s true that I like taking my time, but if I can make the characters take the time that I believe they should be taking, I’m happy with that. I never think in advance of whether that’ll be difficult or not. I just follow my instinct.

Well, the 50-year caftan is really the caftan that I got from my mom. When I wrote the film, I didn’t know why Halim was a caftan maker. I just knew instinctively that I wanted to tell the story of a caftan maker and I grew up with my mother wearing this beautiful caftan every once in a while. I always dreamed of the day I would be able to wear it, but I was way too young. One day she gave it to me, and when I wore it, I understood how beautiful this transmission was because I had a feeling I was wearing part of her youth. There was something that united us. There was a real bond, and she had always explained to me how the maalem [the tailor] had made this caftan, and all the time it had taken. She showed me the detail of the work, so I was fascinated by this.

Later on, I found out that through maalems that this trade was disappearing because there are no apprentices. It’s not being passed on because we live in a world where everything is going too quickly, so I was very, very moved by this. I didn’t think [about the profession] when I started writing the film — Halim was naturally a caftan maker. He was just that, and I understood why afterwards. There are certain traditions, such as this one, that need to be preserved, that are part of who we are, part of our DNA that are beautiful, and there are certain traditions that need to be questioned, such as the way homosexuality in Morocco is perceived and the laws [around it]. Halim is a prisoner of this because he’s trying to keep alive a tradition that is beautiful, but at the same time, it’s another tradition that’s keeping him from being who he truly is, so I really wanted to be able to question tradition through this in a beautiful sense and in the sense that is not so beautiful.

And this caftan, the one in the film, is identical to my mother’s. And I still have her caftan, and I still wear her caftan – it’s the one I wore in Cannes for the premiere. For me, it means a lot symbolically. We lose the value of things. We just want to consume, move on, consume, move on. I think we just have to stop and think about the things that have a real value sometimes.

“The Blue Caftan” opens on February 10th in New York at Film Forum, Los Angeles at the Laemmle Royal and Toronto at the TIFF Lightbox. It will open on February 17th in San Francisco at the Landmark Opera Plaza Cinema , February 24th in Chicago at the Music Box Theatre, March 3rd in Portland, OR at the Cinema 21 and March 10th in Columbus, Ohio at the Gateway Film Center.