Last summer, Mary Wharton had been as anxious as anyone when the realization set in that she wouldn’t be leaving the house any time soon. She had already completed “Jimmy Carter: Rock N’ Roll President” for an opening night premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival that never happened (it debuted later in the summer virtually at AFI Docs) and relocated out of New York, unsure of what the future held. So it was with some surprise and great delight that she received a call from Adria Petty, who had resolved the issues within in her late father Tom’s estate and cleared the way for the release of one of his dream projects, a re-release of “Wildflowers” as it was originally intended as a double album. Not only were there additional tracks that would allow his fans still reeling from his shocking death in 2017 to spend a little more time with him, but Petty informed Wharton, there were hours of unseen footage from the making of the album that had been filmed by Petty’s longtime go-to photographer Martyn Atkins.

“It definitely was a treasure trove of material, and I like to think of it as a little bit of a rabbit hole that I got to fall into,” recalls Wharton. “To have Tom Petty music in my head, 24 hours a day and to dream about it and just have it be in everything, it gave me something so positive to focus on. [With] the pandemic out of control, it was just so soul-crushing and scary and distrustful of other people, so to have something that allowed me to connect again with humanity in a very positive way was such a gift.”

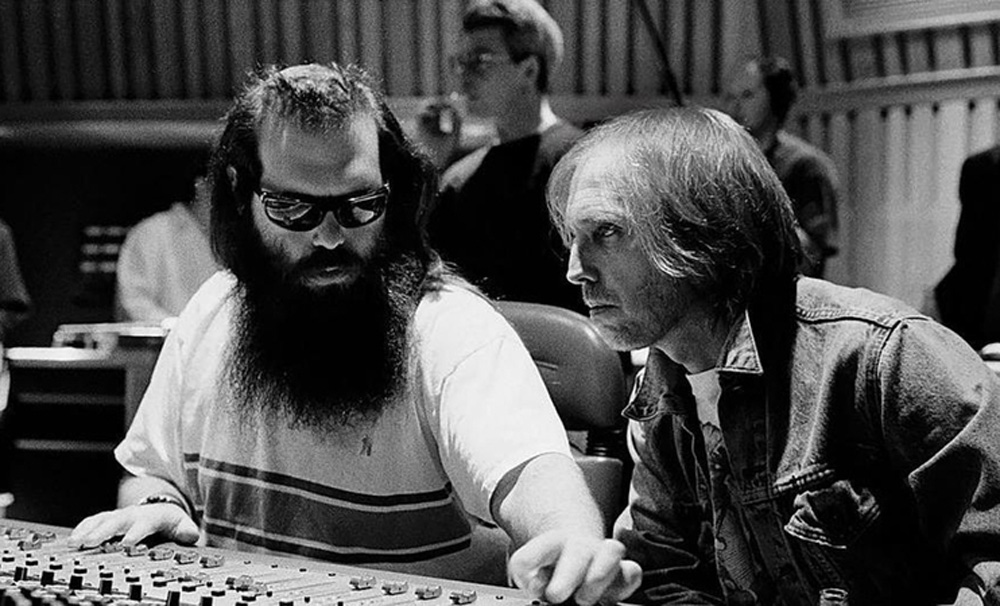

Although the raw footage of Petty would be remarkable all by itself, observing his creative alchemy with producer Rick Rubin on one of the finest albums that either of the two musical titans were involved with, “Tom Petty: Somewhere You Feel Free” offers incredible insight into a pivotal moment in the singer/songwriter’s career, exiting his record deal at MCA after his relationship with the label had been contentious for some time for Warner Brothers with a desire for a creative reset, starting with a stripped-down sound that wouldn’t necessarily involve his band the Heartbreakers (although, even without their name on the marquee, they made their way onto the solo album anyway). It wasn’t only the instrumentation that would be raw, but the lyrics as well when Petty was preparing to separate from his first wife Jane and as Adria recalls in one revelatory detail of many in the film, his time in therapy was opening up “doors of perception” that he didn’t know he had in him.

“Somewhere You Feel Free” allows audiences into Petty’s inner sanctum as much psychologically as physically, with everyone involved in “Wildflowers” from Rubin and fellow producer George Drakoulias to Heartbreakers Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench giving a blow-by-blow for each song, with the film capturing the evolution of “Climb That Hill” from a jazz piano-based track to featuring a driving guitar and how Ringo Starr’s gentle tap on the cymbals changed the entire makeup of “Hung Up and Overdue.” Even those who are most intimately familiar with the album are bound to have shivers sent up their spine with seeing Petty work to certain lyrics or harmonies and the film, by virtue of its unadorned archival material, honors Petty by cutting to the quick of who he was just as he made anyone else feel with one of his songs. With “Somewhere You Feel Free” making its premiere at SXSW, Wharton spoke about crafting such a gem, made more difficult by the restrictions imposed by COVID-19 and how the film gave her a sense of the career she’s built in the unexpected opportunity to celebrate Petty’s.

When you get this material, do you know what you want to do with it as far as whether to keep it entirely in the moment of these recording sessions for “Wildflowers” or go a bit broader into his career?

It was pretty clear cut that I didn’t want to try to do something that focused on his entire career, because that had been done before. There was a film that Peter Bogdanovich made about 14 years ago and Peter Bogdanovich is a little bit of a formidable filmmaker, so I wasn’t going to try and compete. Also, this material was so obviously this perfect little time capsule that it was almost like someone had put it away in a jar and said open in 2020. So there were moments when we thought about bringing in other elements from other time periods, like when George Drakoulias and Rick Rubin in interviews would reference something talking about Petty’s earlier work, and we use a little bit of a “Refugee” performance, from the “Wildflowers” tour — at one point, there was the thought we would try inserting an early a different performance of that song from the time that “Refugee” was released, but we tried it and it was like, “No, this is wrong.” We want to stay in this little bubble of this little time capsule.

It was something that my editor, Mari Keiko Gonzales, and I both agreed. We did try other things — we tried with photographs and certain [other] things where it just either it worked or it didn’t. The only time that it really worked was when we had the sequence of the song, “Harry Green,” where Tom is singing a song about a boy that he knew in high school, and we show him as a younger man, intercut with him from the “Wildflowers” era, because the song takes you back to his memories, and the sort of dreamy, super 8 footage of him as a young man worked. But when it was too forced, like the “Refugee” performance, [which was] Tom in his prime and the Heartbreakers are all young, just going for it, it’s an incredible piece of performance footage that you would think like, “Oh my God, this is amazing. how can we not use this?” But it was like, “It just doesn’t work.” So we didn’t.

One of the things about documentaries is that I have learned is to listen to your film, and the film will tell you what it should be if you listen carefully. Sometimes you have ideas and you try things and you can’t get out of your own way to realize that it’s not quite right. This material was clearly meant to live in the world that it inhabited that we could never leave it really.

Throughout the film, I was thinking about how much math must’ve gone into each scene because, for instance, the introduction of Steve Ferrone happens midway through the film when you’re covering the evolution of “You Don’t Know How It Feels,” and you not only have to explain why Ferrone replaced Stan Lynch as the drummer in the Heartbreakers, but what his specific contribution to the song was and the song has to fit into the overall story of the film, all of which is done so elegantly in one fell swoop.

We did have to really think about, and work on how and when each character is introduced because you could argue that Mike Campbell is Tom Petty’s most important musical contributor. They are co-songwriters on many of the Heartbreakers’ most important tracks, so he should be introduced first, right? Because of who he is, and his place in Tom’s career. But we didn’t do that. We introduce Rick [Rubin] first, because Rick is the inciting incident in our narrative structure. The film manages to follow a very classic narrative arc, where you introduce the character, the world that you’re in and then raise the stakes a little bit.

But you have all that was going on with the interpersonal relationships within the band and [Tom] wanting to break up the band and lose Stan Lynch from the picture, [as] he was having problems with the label, and then he’s having personal problems within his relationship with his wife. and we get all of that out of the way before we even introduce Mike. It was definitely something that was discussed and considered, and the fact that Steve Ferrone isn’t introduced until maybe it’s 20 minutes into the film or more, we talked about that. Ultimately, it goes back to looking at the material, listening to the stories that people are telling us, and building it like a house of cards where you lay out these foundations first and then you can build on them.

I noticed from the credits that Adria Petty was the one who was actually there for the present-day conversation with Rick Rubin, Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench. What was it like figuring out the interviews for this, particularly when COVID likely complicated the ability to conduct interviews in person?

It was tough, and with the Rick Rubin interview and that conversation with the guys, they had decided that they wanted to make a documentary with this footage, but they hadn’t officially brought me onto the project yet. So we had been talking and I wanted to be a part of it, but Adria managed to set up a time with Rick Rubin and he’s a very busy man. I was joking because she was asking me like, “Well, we have this time. Should I just go for it?” And I was like, “Rick Rubin is like Sasquatch, if you can catch him, you better do it. Don’t wait for me.” And they hooked up a Zoom with a laptop on the sat so that I was able to see a feed from the camera while they were shooting, and then I would be able to text Adria follow-up questions, but she did an amazing job with that shoot.

She’s a great director. And she was really a big help in making this film because first of all, she gave me total freedom just to go and do what I wanted to do with the material, but she understood the process enough to really be helpful in pushing a little bit where things could get better. I appreciated that because oftentimes with documentaries, you’re operating on this razor-thin edge of can we achieve what we set out to achieve within the confines of the limited budget and limited resources? And she knew where to be like, “No, I think we can make this a little better.” She was also really open and not afraid of courting controversy, and I appreciated that a lot.

I was so moved to hear that the final lines of the film actually came from an interview with Tom Petty that you were present for as part of your early days in TV production as an associate producer at VH1. Did this feel like a full-circle moment for you?

Definitely, and it was such a cool opportunity to look back, because a lot of times in life, there’s a tendency to question your choices. Becoming a documentary filmmaker is not a great career choice if you care about money, but I’ve lived an amazing life and gotten to meet some incredible people and gotten to be a storyteller, which is such a privilege to be able to share stories with a big audience, so it was great to look back on those choices that you made when you’re younger, and [realize] everything that that I’ve done has led me to this place. And then this project came along really exactly when I needed it. It was in the middle of the pandemic. I didn’t know if I was going to be able to work again anytime soon, and here comes this archival-based film. I didn’t love directing by Zoom, but I made it work. I was grateful to be working and I was grateful to have this creative outlet and it really saved me from falling into a spiral of despair.

“Tom Petty: Somewhere You Feel Free” will play at SXSW on March 17th at 4 pm CST.