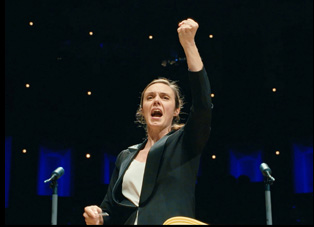

Iowa City seems a lot further away from Paris than it even is in actuality as “Maestra” begins, though Mélisse Brunet would have it no other way. When the only place she says she’s truly happy is a conductor’s podium, she doesn’t mind whatever city or country she’s in, but removed from her native France where she imagines she would’ve never made it to the podium at all after her time at a conservancy, discouraged as a woman from pursuing a position actually presiding over an orchestra where openings are rare to begin with and constantly told to be less expressive of her emotions when that’s what the job calls for. Still, she is beckoned by her birthplace after learning of La Maestra, a groundbreaking competition that brings in female conductors around the world to vie for financial prizes to make their pursuit more sustainable while offering a showcase for all who are selected, ultimately giving the opportunity to 14 candidates to demonstrate their skill.

While it would be fair to call the competition fierce, that would describe the contenders’ demeanor rather than their attitudes towards one another in director Maggie Contreras’ engaging chronicle of the 2022 edition of La Maestra where Brunet is joined by a host of other conductors from different backgrounds who have shared in common the same obstacles to getting a stable career in a predominantly male field. In addition to Brunet, Contreras follows Anna Sułkowska-Migon from Krakow, the daughter of a conductor who is warned by her own family of attempting to try and follow in her father’s footsteps with their warning bearing out so far as she’s only had four concerts to conduct since turning professional; Zoe Zeniodi, a Greek conductor whose dream has led to a nomadic existence, taking gigs wherever she can at the expense of having more time to spend with her family, and Tamara Dworetz, an aspirant from Atlanta who worries her impending pregnancy will limit an already scarce amount of opportunities.

What may be seen as drawbacks in a patriarchal culture are reflected as markers of extraordinary poise in “Maestra” where one can see how personal experience has shaped how each of the conductors express themselves on the podium and take command of the musicians in front of them. Contreras clearly takes the advice of pioneering conductor Marin Alsop, a judge of La Maestra who confides, “Their voice is in their hands, so watch their hands,” and turns the film into a gripping profile of perseverance and passion. With the film premiering this week at Tribeca, Contreras spoke about how she came to direct “Maestra,” developing a striking cross-cutting methodology to draw parallels between the women competing and their lives on and off the podium as well as conveying what a conductor really does.

Well, thank you to NPR, because many an idea for me comes from just listening to the radio. And “All Things Considered” had covered the first iteration of the competition. It started in 2020 and they managed to pull off the first one during COVID, so that’s how I heard about it and then reached out to the powers that be at the Paris Philharmonic and the Paris Mozart Orchestra and spent a few months getting to know them and convinced them to give this American access to their incredible competition. They introduced me to all 14 candidates and those candidates all said yes, so then it was a matter of deciding who we follow.

Was that tricky to decide upon?

I’ve found there is beauty in a limited palette, and one struggle we had was this was during the pandemic, so even though all 14 of the candidates were willing and excited to participate. I didn’t have access to all 14 because I couldn’t go to all countries. Not all were open, and then budget helped whittle down what was possible, but I’m a firm believer if you train your lens on anyone, there’s going to be a compelling story, so I was convinced that any of these 14 would have been great stories. I filmed with more than you see in the film, and then it was a matter of what story pieces were able to be woven together, and the time that we needed to spend to fall in love with a subject before being able to root for them in a competition setting.

It does ultimately coalesce around Melisse as a central figure, which is unusual for a documentary of this type where you’re following a number of subjects. How did that evolve?

It happened in the edit. I knew that this world was going to be interesting and the fact that it’s a competition is immediately entertaining at its very base level. You have these women who are very unique in that they all have this very strange job called conducting that no one seems to know anything about, so the idea of who’s going to win was never a pressure for me because I was fully convinced that these women’s personal stories were going to be compelling enough that no matter who wins or who loses. It’s not the competition that’s at the heart of the story, but the human stories and with Melisse, I didn’t know when I sat down with these humans what their backstories were going to be. I knew some from pre-interviews on Zoom, but once you start sitting across from someone, I’m sure if we talked long enough, we’d be able to find really compelling things about each other.

And I never could have imagined what Melisse’s backstory was going to be. Winning the competition is not her only dragon she has to fight. She’s a hero on a hero’s journey and she thinks that the competition is her dragon to slay, but it’s actually not. It’s something else. So she always had a little bit more of a hill to climb than the rest and the story is always in the struggle, isn’t it? The stakes are high, and for her, they were the highest, so she became that central backbone.

There’s a scene that sets the tone for the film early on where Tamara can be seen at home, on her back, imagining herself conducting cross-cut with her actually on the podium on the job, and it allows you formally to work that idea in throughout the film to compare their professional and personal lives, sometimes between one another or just for them individually. Was that style in mind early?

What hit me in spending time with these women is that it’s such a solo endeavor. It’s very quiet and a score, because it’s written on this page in black and white, [exists] like a really amazing novel and in the real world, a conductor doesn’t have much time to rehearse with an orchestra, so they have to go over and over and over in their brains, practicing their gestures and imagining themselves on the podium and in front of the orchestra. They sit alone in their own quiet space and it’s a very athletic thing that they’re doing, like when athletes talk about imagining sinking that basket or imagining throwing that touchdown. It’s almost a muscle memory and what’s going on in their internal life is where the rehearsal is happening, so the only way to show that to an audience is to do this cross cutting.

Now, I didn’t have that in mind when I shot [Tamara] at the podium alone, I just said, let me see you rehearse and she took that moment, but her on the floor [of her home] is how she rehearses [most of the time]. She has this thing where she’s too animated with her legs, so her way to get [the music] into her body — into her torso — is to lay on the floor, so that her legs can’t do much, so that’s what she [practices] and it was just a matter of being around for it. Then [when we come back to that cross-cutting] at the end, it’s very interesting. One of the hardest things about making a documentary in my experience is getting feedback and how much of that feedback you listen to and really having to know what you like as the filmmaker and stick to it when you know it’s working, even if you are not sure. I was told to cut that moment [towards the end] so many times, like “you’re stepping on the performance [of the winner],” you’ll get it when you see the full film. It’s not about her. And It’s my favorite part of the film.

One of mine too. And you really get the emotion from the performances from the way this is shot. Was there a trick to capturing it with the camerawork?

Those props I have to give to Olio — that is a live broadcast on Arte, so I worked with the production company who filmed it the first time and was going to film it [the year we were capturing], and knows that space very well. I made sure that their camera placements served both the live broadcast and the documentary, so there were 10 cameras on stage. There is one slider and one camera on a joystick and the rest were on sticks, locked down.

Between that and the way you’re able to listen to them talk about conducting while actually watching them do it gave me an understanding of this that I had never had before. Was that complicated to tie together?

That was actually one of the hardest things. In the first act, [which is about] 25 minutes, you have to understand the stakes that these people are going through. You have to fall in love with them and you have to teach people about conducting so then when we get to the competition, they actually can sit back, [thinking] I know what this is about now, so let me watch and judge as we go along and I knew that was going to be critical to enjoy the competition. If you don’t know anything about the sport, it’s going to be harder to watch.

So there are these Greek chorus moments where we meet someone, we take a step back and we talk about the mechanics. We go back to their lives, we take a step back, we talk about more of the mechanics so that we understand them as human beings, but also as artists and the technicalities of [what they do] as well. One of my goals was for everyone to step out of watching this and be able to explain to someone what a conductor actually does. And let’s use the word interpretation. That’s the simplest way I tell people who haven’t seen the film and people also ask like why is it important for a woman [to be a conductor] and it’s the same answer. It’s representation because it’s interpretation. You take the script of “The Godfather,” and you give that Godfather script to five different directors and you’re going to have the same story told a bunch of different ways. Same with a score. It’s a script, and it’s being interpreted through a human being, and they are imprinting on it, so interpretation is the key there.

“Maestra” will screen at Tribeca Festival at the Village East on June 9th at 5:30 pm, June 10th at 3:30 pm and June 15th at 8:45 pm.