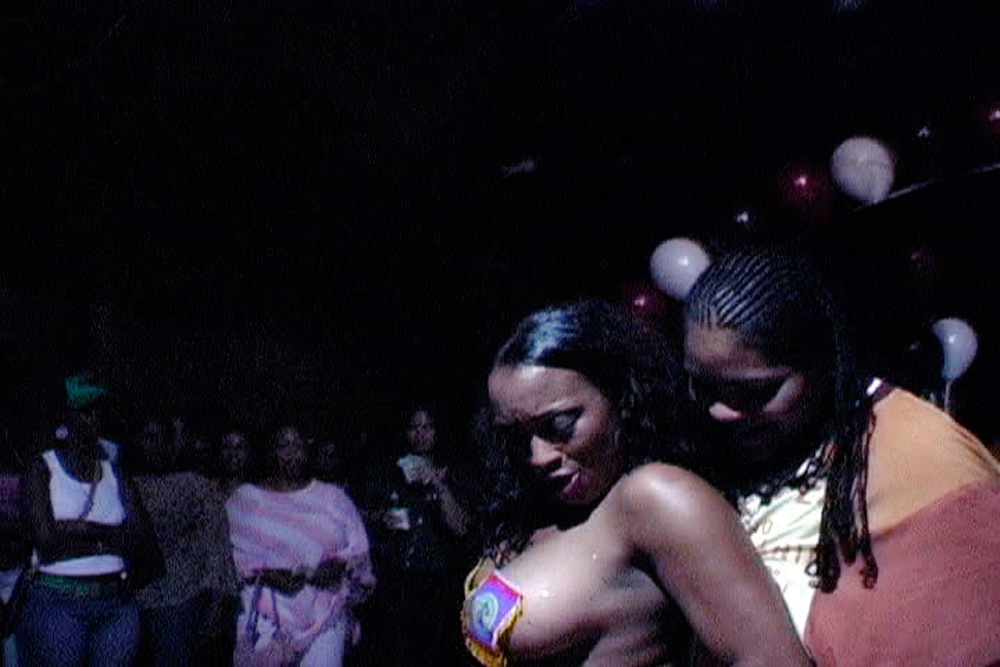

It’s saying something that Leilah Weinraub’s “Shakedown” is every bit as wild as its subject, the titular band of black lesbian strippers who held court in Los Angeles during the late 1990s and early aughts. Brought to you by the impossibly cool folks at Memory, who have carved out a nonfiction niche of being the trusted friend who hands you an unmarked cassette and tells you to “just watch it” after supporting such films as Theo Anthony’s “Rat Film” and Dean Fleicher-Camp’s “Fraud,” “Shakedown” has the lurid pull initially of an episode of HBO’s ’90s “Real Sex” series, presenting stripper parties so ridiculously over-the-top you’d be hard-pressed to believe such a group actually exists as you learn the names of the “Angels” of Shakedown that include the likes of Trinitee, 360 and Tight-Eyez, followed by raw and explicit footage of the women at work twerking and krumping, long before such moves were in fashion. However, a sophistication soon seeps in, both in terms of Weinraub’s intent and the women who, to varying degrees, aren’t to be confused with who they are when they’re performing.

Naturally, contemplative interviews in quiet settings juxtaposed next to scenes of nude bodies being doused with whipped cream as a raucous crowd throws dollar bills at the women will offer some immediate separation in personality, but it’s clear subjects such as Egypt (real name: Aisha) and Miss Mahogany have thought a lot about the disconnect between their on and off-stage personas well before Weinraub puts the question to them and often the filmmaker is careful to present her subjects in their daily life before taking in their nightly exploits, allowing the first impression to take away the usual judgment.

As a group within the group emerges as central subjects including Shakedown’s founder Ronnie Run, who confesses she didn’t know she was gay until well into her twenties, the weight of being a minority within a minority grows heavier, and under its inherent flash, Weinraub subtly builds a well-rounded examination of the expectations the women are fighting against, whether it’s getting upset at playing cards with their images on them that project them in a different way than they see themselves or one of the strippers and her girlfriend embarking on a pregnancy through artificial insemination and hearing on a public access call-in show that not everyone approves. Even the stripping scenes become transgressive for reasons you might not expect, with the mere act of seeing the largely-female audience receiving sensual pleasure from stripteases – a far cry from usual depictions of silliness at male strip clubs – and the struggle to wholly inhabit one persona over another, as one stripper Jazmyne becomes pissed off at a customer review that compliments her as being “the girl you take home to mom,” leading her to wonder what she’s doing wrong in her freaky lapdances.

Yet the audacity in “Shakedown” is actually in its less outrageous moments, presenting the uneasy relationships people make with each other and within themselves that form at the fringes of marginalized communities that have had to coalesce around a single identity to have power rather than the luxury of defining who they are individually on their own terms. That Weinraub’s tribute to the Shakedown Angels has all kinds of rough edges visually, shot on the earliest DV, and otherwise, is wonderfully fitting.

“Shakedown” plays once more at the True/False Festival on March 4th at 8:30 pm at the Big Ragtag. It will next play in New York at MoMA on March 18th.

Comments 1