Even with Linda Fiorentino’s unforgettable anti-hero in “The Last Seduction,” it had to feel like if anyone was getting away with anything in the contemporary noir classic, it was the filmmakers themselves.

“We’re really fortunate the way movies work is if you shoot for a week, you’re basically stuck for the price of the whole movie,” John Dahl recalled after a retrospective screening at the Aero in 2019. “If you cancel the movie in the first five days of shooting, they can like just pay everybody out, but because the guy [at our production company ITC] didn’t quit until Saturday, the movie got greenlit for the rest of it and the guys that took over could’ve care less about the movie.”

“They thought it was sort of just like a skinner — they wanted more skin in it,” producer John Shestack added.

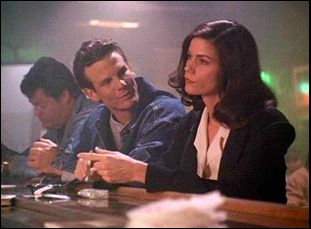

“I was telling that to Linda,” said Dahl. “It was the day we were shooting that scene in the bar where Linda puts her hands in [co-star] Peter Berg’s pants, and I said, ‘You know what we should do is just do a graphic shot of her fondling male genitalia,’ and I said to Linda, “Would you be okay with that?” She said, “I would love to.” And so I said, ‘Peter, do you want to do that?’ He said, ‘No way.’ [Then] I asked the key grip, “No way.” One of the PAs, ‘No way.’ — there wasn’t a guy there that wanted to do that scene, which is why we didn’t shoot it, but I would have just loved to see [the execs’] faces in dailies watching…not the kind of skin they were looking for.”

Low expectations might’ve ultimately benefitted “The Last Seduction,” which Dahl may have only had 23 days to shoot for a company that quickly sold off the rights to Showtime after it was in the can, but the lack of supervision surely is one of the reasons that it’s still celebrated all these years later and on the film’s 25th anniversary, Dahl, Shestack and the film’s editor Eric Beason spoke with the late F.X. Feeney about having to be as quick-witted as the irresistible con artist at its center. (The film returns to the American Cinematheque on the other side of town this week at the Los Feliz 3 where it will be presented by “You Must Remember This” host Karina Longworth’s series of Erotic Tuesdays attached to the current season of the podcast, and for those out of town without access to Scorpion Releasing’s fine Blu-ray edition of the movie, it’s currently streaming on the Criterion Channel.)

“What was great is we got this script where John’s thought it was a black comedy, not a film noir, I think. The writer [Steve Barancik] thought he was doing a Sharon Stone movie — at first, a big, glossy, femme fatale movie, but it turned out to be this amazing little noir black comedy,” said Shestack. “And [then] with Linda Fiorentino, we took the script apart and we tried to find every hole in it and there were no holes in it.”

“You realize she is just bad to the bone from beginning to end, and she probably has 85% of this plan down the minute she meets that dope in the bar,” said Shestack. “If anything, she’s a good shot who turns into a better shot, but she doesn’t change her mind, and that’s what’s so liberating about film noirs and the movies John does.”

Yet what made the character so appealing on screen led to it being all but impossible to cast when actresses that met for the role could be concerned with being seen as unsympathetic and actors were scared away by the thought of playing a cuckold.

“A lot of people didn’t want to play this part,” Dahl said specifically of Bridget, who saw at least 30 actresses before meeting with Fiorentino, who quickly saw the potential. “John [Shestack] and I went and met Linda and Linda said something to the effect of ‘This is the first time I’ve read a script where I get to be the guy instead of the girl.’”

As for the men Bridget would hoodwink, Dahl got a script to Pullman, who he had known back when both were in Montana and the “Sleepless in Seattle” star actually taught a Directing for Theater course as a grad student that Dahl took at Montana State University, and he signed on to play Bridget’s husband Clay. However, finding Mike, the “aw shucks” Beston local that Bridget manipulates, proved far tougher.

“We interviewed a lot of guys, but Peter came along and I sat in my office with him and he broke the script down and understood exactly what the movie was, which was really interesting [because] most guys said, ‘I don’t want to play this part,’ but he understood how that character needed to work in the story,” said Dahl. “We were doing one of the early scenes that we did in the house where [Mike says] “Wendy, I want you to love me” or something like that, and at the end of the scene [when his advances are rejected] in the script he even said, “Well, go fuck yourself.” And she said, “Yeah, right. Tomorrow night at 8 o’clock,” but I just remember [Berg] saying that [line] and [then] saying, ‘That just seems wrong. I don’t [need to say that].’ And it felt like terrible director advice to mention another actor to an actor, but [I told him] ‘You just need to be Jimmy Stewart in this movie,’ and it clicked for him and he embraced the nice guy in himself [and allowed himself to be] there to be mowed over by Linda Fiorentino every day.”

It was actually the Mike character that grabbed Dahl’s interest in “The Last Seduction” in the first place when the filmmaker could see a little bit of himself in the “the guy in the small town who wanted to get out of there and [in meeting the New York-born Bridget] it’s something bigger,” and although Beston, a suburb of Buffalo, was thousands of miles away from where he grew up in Montana, it felt very similar.

“I had just been to my sister’s graduation in Laramie, Wyoming [before getting “The Last Seduction” script] and I think I came back and said, ‘What struck me being in a small town again is that everybody says hello to you, so I think we added that whole sequence when [Bridget’s] in the small town and everybody says, ‘Hey, good morning, good morning.” There was a Boy Scout troop that was walking [around town], and I said to John [Shestack], ‘It would be great if we could get these cub scouts to [be in the film], so John went over and [asked] and it just so happened that there was a SAG rep there that day, so we got in all kinds of trouble. We had to pay all those people to get them into SAG…”

“Then we might have had to explain what the movie was, which was sort of embarrassing,” Shestack laughed, though given the film’s idiosyncratic tone that wasn’t an isolated incident when even some of the people working on it could use an explanation. Dahl described having to talk Berg through the ridiculous sex scene that takes place outside the bar where Mike and Wendy first meet, doing the deed as she hoists herself up on a chainlink fence that his back is up against.

“Peter didn’t really want to do it,” Dahl said. “He just thought it was obnoxious and over-sexualized and gratuitous. And Linda and I are trying to talk him into doing the scene as the sun’s coming up and we’re afraid we’re going lose [the darkness], and basically I’m trying to say there’s nothing sexual about it, it’s just hysterical. They’re having sex on a fence outside of a bar. Ultimately, Linda talked him into doing it.”

The production also went through with a sex scene that was less likely to make it into the film, though it had been in some way a part of Barancik’s original vision of seeing Wendy and Mike playing different roles in their relationship, acting out certain fantasies. Shestack and Dahl corrected a popular apocryphal tale from the set in which studio executives descended on the production upon seeing a scene set in a high school gymnasium where Wendy strips down to wearing only schoolgirl skirt and suspenders over her breasts, and as legend has it, the executives thought the film was going too far, though Shestack said it was actually the opposite issue.

“It was like, ‘you better have this scene in the movie,’” Shestack said, with Dahl adding that it was the executive’s favorite scene in the script. “And he came to the set that day to make sure that we shot it, which we did, but it just was silly. It was embarrassing to all of us, so what we ended up doing was saying, ‘There was a problem with the negative,’ because we really felt it shouldn’t be used and they realized they didn’t need it.”

This took time away from an already pressure-filled shoot that Dahl knew had to economical to work. After Scott Chestnut, the editor who worked with the director previously on “Red Rock West” and later such films as “Rounders” and “Joy Ride,” gave him “a bad time” about so many static shots that would need to be cut together later to give it kinetic energy, Dahl decided to shoot the film in long masters in the start of a fruitful collaboration with cinematographer Jeffrey Jur with the hope of making things easier on himself during the shoot and eventually for editor Eric Beason and associate editor Louis Cioffi, who the director noted were ideal partners to scrutinize every frame when “between the two of these New Yorkers, one’s a New York Mets fan, one’s a Yankees fan, [so] the editing room was a riot.”

“Eric said, ‘Don’t worry about it. This stuff takes so long. This guy will be out of here in two hours because he won’t be able to sit through it because it’s film [we had to cut]’ and he would say to Louis, ‘Okay, go get that box’ and then Louis would leave and five minutes [would] go by and he’d come back in with a box of film and then we’d load it up on the Steenbeck,” Dahl said about stretching out the process. “ And Eric was right. Basically this guy was out of there within two hours.”

In the end, there were few outside opinions on the film when ITC didn’t bother with test screenings and sold it off to cable to break even without considering what they had, essentially tying the hands of any potential theatrical distributor when its destiny was predetermined. Dahl had shown it to students at AFI and was encouraged by the response and the film’s international team landed it a berth at the Deauville Film Festival, which the director couldn’t attend himself, but remembered getting a call from Fiorentino and Berg in the middle of the night shortly after its French premiere, who said, “People are going crazy over the movie,” and as he noted, “October Films happened to be there.”

The Focus Features progenitor was led at the time by Jeff Lipsky, who fit right in amongst the sly dogs already involved in bringing “The Last Seduction” to the screen and recognized between the strength of Fiorentino’s performance and the fact that the film had aired on Showtime before a traditional theatrical run could stir up a controversy over the Academy of Motion Pictures’ rules that actually could be used to drum up publicity for the film.

“I don’t know that there was any chance that movie was getting Linda or any of us an Oscar nomination, but it was a great story [that] she’s ineligible because these doofuses screened it on Showtime,” said Shestack. “It was a great story that had kind of the added benefit of being true. There was a great groundswell.”

Dahl remembers the surreal feeling of sitting at Sardi’s with Lipsky after thinking that the film had been left for dead, only to await the delivery of the New York Times to see the reviews.

“We read the review, and I remember I had to read it like three times,” said Dahl, who added the two prints that October struck for the film had to be bicycled around the country. “I thought, ‘Wow, they kind of like it.’”

Eventually even the execs at ITC had to like what “The Last Seduction” became, producing the version they probably wanted in the first place with a Joan Severance-starring sequel to capitalize on the notoriety of the first involving none of the creative team of the original and Dahl and Shestack could come to embrace the company’s primary contribution to the production, the film’s title aimed squarely for those perusing Blockbuster video shelves or late night cable when the original title “Buffalo Girls” was nixed for confusion it could’ve caused being mixed up with a recently published Larry McMurtry novel.

“They chose this title from a list of tacky film titles that would sell on foreign TV,” recalled Shestack, who could take pride in giving the film a good name in spite of not having a say in the matter. “We had to get used to it, but now it seems like a good title.”